Following months of speculation, EPO Board of Appeal 3.2.01 yesterday issued decision T 439/22 referring questions to the Enlarged Board of Appeal on the extent to which the description and drawings should be used in claim interpretation.

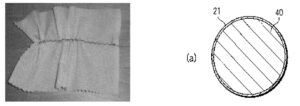

The claim feature at issue was: “in which the aerosol-forming substrate comprises a gathered sheet”. The key question in this opposition case is whether the claim feature “gathered” should be interpreted narrowly as a complex 3D structure in line with the left hand side illustration below, based on the clear common general knowledge. The opponent contests this and argues that a broader express definition given in the patent should be adopted which covers a sheet formed into a cylinder in line with the right hand side illustration from the prior art below.

The following questions were referred:

- Is Article 69 (1), second sentence EPC and Article 1 of the Protocol on the Interpretation of Article 69 EPC to be applied to the interpretation of patent claims when assessing the patentability of an invention under Articles 52 to 57 EPC? [see points 3.2, 4.2 and 6.1]

- May the description and figures be consulted when interpreting the claims to assess patentability and, if so, may this be done generally or only if the person skilled in the art finds a claim to be unclear or ambiguous when read in isolation? [see points 3.3, 4.3 and 6.2]

- May a definition or similar information on a term used in the claims which is explicitly given in the description be disregarded when interpreting the claims to assess patentability and, if so, under what conditions? [see points 3.4, 4.4 and 6.3]

There has long been a tension between the two main EPO approaches to claim interpretation:

- The “own dictionary” approach, in which terms in the claims can be defined in the application; and

- The “primacy of the claims” approach, in which clear terms in the claims are interpreted by the skilled person without the aid of the description.

Attempts have been made to reconcile these approaches by holding that the “own dictionary” approach only applies where the relevant term in the claims is unclear, and that limitations cannot be read into the claims from the description. At the same time, EPO case law also holds that claims should be interpreted based on the whole disclosure of the patent with a mind willing to understand, and that the “broadest technically sensible meaning” should be adopted. With so many, often conflicting approaches, it is no wonder that a lack of legal certainty remains.

The lack of agreement between the Boards on the legislative basis for claim interpretation for substantive patentability exacerbates this uncertainty. Recently, T 1473/19 opted for Article 69 EPC and T 169/20 relied instead on Article 84 EPC. It is safe to say that neither article gives clear support for the “primacy of the claims” approach favoured by these Boards. Article 84 doesn’t even expressly mention claim interpretation, while Article 69 if anything states that “the description and drawings shall be used to interpret the claims”. The situation is even more complex when the approaches of the national courts are taken into account, as they tend to favour the “own dictionary” approach.

T 439/22 outlines three main points on which the Board considers there to be divergence at reason 3.1:

– legal basis for construing patent claims

– whether it is a prerequisite for taking the figures and description into account when construing a patent claim that the claim wording when read in isolation be found to be unclear or ambiguous

– extent to which a patent can serve as its own dictionary

The decision then discusses the various approaches of previous Boards supporting this finding of divergence. Underlining the point we made above about the difficulty of finding a consistent rule on this issue, a large number of decisions and legal rationales were cited.

Reason 4 of the decision explains why this is a point of fundamental importance. Several national decisions, as well as the UPC CoA decision in Nanostring v 10x Genomics were cited. In our view, claim interpretation is such a central issue for so many aspects of patent law, that it is hard to dispute the fundamental nature of the referral.

While we welcome this brave move to question the status quo by Board 3.2.01, we can’t help but fear that the desired legal clarity may not actually be achieved with this case. As the difficulties on finding a compromise on Article 69 EPC over the last few decades show, finding a golden rule defining a fair balance between the claims and the description is difficult.

As Bob Dylan put it in “All along the watchtower”:

There must be some kind of way outta here

Said the joker to the thief

There’s too much confusion

I can’t get no relief

We therefore welcome the decision to refer, in the hope that this will lead to improved legal certainty and some long overdue relief.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Patent Blog, please subscribe here.

The decision has been commented in another blog.

The question of application of Art 69 and Art 1 of the Protocol in procedures before the EPO has been lingering for a while, and it is good that a board has now decided to refer this important question.

It is to be noted, that the analysis of the diverging case law by the referring board is quite impressive and actually shows the necessity of such a referral.

The referral has been limited to the application of Arti 69 (1) and Art 1 of the Protocol on Interpretation, when a claim has to be assessed with respect to Art 52-57.

The board did not bring in Art 123(2). This position differs from that adopted in T 450/20, and T 1473/19, In T 450/20, the board refused to refer questions about the application of art 69 and its Protocol to the EBA.

Although the boards in T 450/20 and T 1473/19 considered, the primacy of the claims, they considered that Art 69 its Protocol should also be applied when assessing added matter.

It is to be hoped that the EBA does not start rewriting the questions in order to answer questions which have not been referred to it.

The referring board related its questions to Art 52-57, but, for apparently good reasons, did not mention Art 123(2). In this respect a “disclaimer” on Art 54(1 to 3) could appear appropriate in order not to jeopardise the “gold standard”.

This is a good point about Article 123(2). I also noted that Articles 83 and 84 are not mentioned. But are you not concerned that by leaving these out, we’ll be left with uncertainty about these other issues?

Addressing Article 54 but not Article 123(2) to me seems problematic precisely because of the Gold standard, as a determination on Article 54 would no doubt be argued to apply accordingly to Article 123(2).

This is a fundamental question indeed. But in my opinion, there is a rather simple solution. The clarity of the claims and the consistency between claims and description is solely within the control of the applicant/patentee. Hence, any lack of clarity must be construed against the patentee. In questions of patentability, the broadest technically sensible meaning must include any broader meaning assigned to a claim term by a definition in the description. In questions of infringement, a more narrow definition of a claim term in the description must be applied, already for ascertaining legal certainty for the public. With this principle, the applicant/patentee is prevented from achieving an unfair advantage arising from lack of clarity or inconsistency between claims and description.

This is indeed a simple solution, and it fits with something I found slightly surprising about the decision – that the Board didnt simply adopt the “broadest technically sensible” meaning given in the description. My only concern is that adopting different interpretations for validity and infringement is something that many practitioners will find difficult to stomach as it would disconnect the scope of protection from the invention.

As to whether the clarity and consistency is solely within the control of the applicant/patentee, I agree generally but would only note that sometimes terms that seemed clear when drafting later seem less clear when confronted with unexpected prior art. This, tied to the EPO’s famous inflexibility on amendments, can make patentee’s life difficult!

I actually believe that my suggested approach would incentivise practitioners to draft claims and descriptions that are consistent. Using a broader definition of a term in the description would risk that the claim is found not patentable over prior art that is outside the scope of protection defined by the claims alone. Using a narrower definition in the description would risk that the scope of protection is eventually found smaller than the literal claim scope – in addition to the risk that the claim is unpatentable over a prior art that this outside the narrow definition in the description. Net, neither scenario has a benefit for the patentee. The drafting practitioner is incentivised to create consistency. The public is better informed about the scope of protection.

Grant proceedings and infringement proceedings will always be handled by different bodies. in bifurcated proceedings, infringement and validity are determined by different courts, often on different time scales. Different bodies applying different claim interpretations is just a fact of life. As an inhouse practitioner, what I find difficult to stomach is that I often face difficulties explaining to my internal stakeholders why I cannot precisely construe claim terms and thus the scope of protection. They expect me to provide them with legal certainty and cannot offer it to them.

As to your last point, Adam, a prudent practitioner should, in my opinion, not rely on any term that seems clear, but rather err on the side of caution and use the description to explicitly define all key terms used in the claims. This may involve copying from a textbook, but it creates legal certainty. And even textbooks differ in their definitions of the same term, at least in nuances. I do not believe that many technical terms have an accepted meaning in a technical field with a level of precision that is desirable form the viewpoint of claim clarity and legal certainty.

Please refer to my comments at the beginning of the thread and at my reply to “Concerned Observer”.

As there is case law saying that a clear term cannot be given a more limited meaning to a feature of a claim, why should it be that in presence of a clear, or even an ambiguous feature, the “broadest technically sensible” meaning should be adopted?

Clarity and consistency are indeed solely within the control of the applicant/patentee. Why does the applicant/patentee not bring this “broadest technically sensible” meaning in the claim?

The reasons for this are pretty obvious: a broad claim, or the possibility to broadly interpret an ambiguous feature, can easily lead to a novelty and/or an inventive step objection.

On the other hand, the applicant/patentee will bring this “broadest technically sensible” meaning in the description, so as to catch as many as possible potential infringers. As the granting system under the EPC is as it is, the applicant/patentee cannot have his cake and eat it.

This also explains the reluctance of some applicants to adapt the claim before grant under Art 84, support.

To me, the “broadest technically sensible meaning” sounds suspiciously like the “broadest reasonable interpretation” approach that is applied across the pond. Whilst not the worst idea in the world, it does suffer from one, rather serious problem: lack of legal basis.

When it comes to interpreting the claims of a European patent (application), we need to first consider what the EPC has to say about the matter. As far as I can see, Article 69 EPC contains pretty much the only relevant provisions on this point.

Certainly one can quibble about the potential differences between “invention” and “extent of protection”. However, even if one were to seek to define unique criteria (i.e. different from those in Art. 69 EPC) for determining “the invention” defined by the claims of a patent, serious problems would arise if those criteria were in any way incompatible with those of Art. 69 EPC. For example, it would be a problem if application of those criteria resulted in the “invention” defined by the claims always differing in significant respects from the “extent of protection” conferred by those claims.

Personally, I would prefer an approach to claim interpretation that aligns with general principles of (national) law regarding the interpretation of documents. That is, whilst recognising the primacy of the claims, I believe that it is important to consider the INTENDED MEANING of the terms of the claims and, more importantly, the CONTEXT in which those terms are used.

It is perhaps too much to ask EPO examiners to consider matters in such detail. I can therefore accept first instance examination conducted upon the basis of a more “rough and ready” approach, such as the standard / accepted meaning in the art. However, it is important to acknowledge and accept the limitations of that approach. That is, it is important to acknowledge that the interpretation applied during examination is APPROXIMATE, and should NOT form the basis of final, unappealable decisions.

I want to explore your “serious problems might arise” fear. Is it not so, that at least the national courts of England and Germany (Formstein) are doing exactly what you fear, namely construing the claim for the purposes of its validity differently than for the purposes of what infringes that so-construed claim, under Art 69 EPC, as an “equivalent” to the claimed “invention”?

And if they are already doing this, what exactly are the formidable “problems” they wrestle with, each time they do this?

Max, an “equivalent” is always defined by reference to “the invention”.

Equivalents can certainly cause problems, such as:

– determining which embodiments are “equivalent” to the claimed invention; and

– figuring out how to deal with arguably “equivalent” embodiments that are prior art to the claimed invention.

However, those are problems that can be settled in a predictable manner (ie by establishing and applying common principles). Also, because of the intimate link between an “equivalent” and “the invention”, the extent of protection conferred by the claims still tracks with “the invention” defined by those claims.

On the other hand, using different (claim interpretation) principles to determine “the invention” and “the extent of protection” creates a complete disconnect between the two. That is, instead of the two tracking one another (eg with the extent of protection being centred on “the invention” and forming a penumbra around it), they will differ in case-specific and potentially very significant ways.

To illustrate, consider a patent specification whose description provides an unusually narrow definition of a key term used in the claims. Using the same (Art.69-based) principles to determine both “the invention” and the extent of protection could lead to a narrow but valid patent. On the other hand, using the EPO’s current (acontextual) approach to claim interpretation could instead lead to rejection of an application that, if granted, would have been considered perfectly valid by the national courts.

No time now but your thoughtful contribution deserves a reaction.

Perhaps unwittingly, you (I think) make the case for the EPO’s “acontextual” approach, pre-grant. The driving force is the EPO’s urge to let through to grant only claims that satisfy Art 84 EPC (because all duly issued claims will be immune from Art 84 attack after grant). The EPO sees that as justification enough to persevere with its ultra-dirigiste line of claim interpretation, during examination of applications. Or not?

The interesting question is how the EPO shall interpret claims after grant, in opposition proceedings. But will the EBA be confident and public-spirited enough to pronounce on that? I doubt it.

What does Art 69 say:

Art 69(1), second sentence says: “the description and drawings shall be used to interpret the claims”. This is however to be brought in correspondence with Art 69(1), first sentence, which says: “The extent of the protection conferred …… shall be determined by the claims”.

It does not say that the validity of the claim has to assessed taking into account the description.

This is why some boards have considered that when a claim is clear and/or technically sound, there is no need to look at the description.

Other boards have said that the description cannot be used to give a feature in a claim a more limited interpretation than that resulting from the plain meaning of the feature of the claim.

A look at the description might be necessary if features of claims are ambiguous. In case of an ambiguous feature, the broadest interpretation possible is then to be used. In this case, the description cannot be used to give the ambiguous feature a narrow interpretation.

That Art 69(1) is to be used when assessing Art 123(3) is a consequence of the plain wording of Art 123(3). This is in my opinion the only case in which Art 69 should be used in procedures before the EPO.

A systematic interpretation of the claim according to Art 69, as it is done in German procedures (Auslegung) before any decision on infringement or validity is not required by the EPC. If the legislator wanted this, a corresponding Art an/or R would have been introduced in the EPC.

You are quite correct that Art. 69 EPC is concerned with extent of protection. However, ignoring Art. 69 (and Art. 1 of its associated Protocol) for assessing the validity of a claim still leads to the kind of problems that are discussed in my response to Max above.

Also, as I have previously pointed out, Art. 69 EPC and Art. 1 of its associated Protocol pretty much reflect the standard approach (under national laws) to the interpretation of terms used in legal documents. Departing from such an approach is therefore certain to lead the EPO to interpret patent claims in a manner that not only lacks any clear legal basis but that also conflicts with the approach adopted by national courts (which are also bound by the provisions of the EPC).

I like your comment, FP, about lack of clarity working against the Applicant/Patentee.

It reminds me of my first months in the patent profession, back in the early 1970’s, when my trainer warned me about use of the word “for” in a patent claim. Does it mean “suitable for” or “intended for”. Beware! The wider meaning will be applied against you on validity over the prior art but the narrower interpretation will likely be applied against you when considering what acts infringe. At the EPO, “for” means “suitable for”, right?

If you claim, for example, “A piston for an air pump” and, much later, assert it against a manufacturer of water pumps what might happen is that your failure of clarity results in your losing everything. Not only is there no infringement (because there is no air pump), but also the claim lacks validity over a prior published water pump whose piston is suitable for pumping air.

The writers of the EPC took a deliberate decision to exclude Art 84 EPC from the grounds of invalidity. One consequence is the EPO’s obsession with clarity prior to grant. Another is the present referral. But hey, what’s the better option? Do we really want to amend the EPC to put Art 84 into the grounds of invalidity, post-grant? I hope not.

I am afraid that a correct answer is always case-by-case and based on common sense, so the answers in the referral will not help at all, on the contrary, they will limit the use of common sense in each specific case, or the answers will be so general that they will not give any concrete guidance…

My thanks go to Proof of the pudding,

In a comment on my blog Proof of the pudding has given a very pertinent comment on the problems raised by the presidents decision not to stay the procedure.

Reference was made to T 166/84 (OJ 1984, 489) and Guidelines E-VII, 3.

According to T 166/84, a first instance not staying a procedure when there is a question pending before the EBA which may affect the outcome of a case, then it commits a SPV.

According to E-VII, 3, when there is a question pending before the EBA which may affect the outcome of a case the proceedings may be stayed by the examining or opposition division on its own initiative or on request of a party or the parties. If a party requires a stay, simply answering that there is a contradictory decision of the president may not be sufficient.

As T 166/84 is not mentioned in the Guidelines EDs/ODs are not bound by it, and hence, can ignore it.

But can EDs/ODs ignore the crystal clear Guidelines? I have some doubts.

Although the Notice of the EPO does not mention it, Art 10(2,a) can be applied when administrative matters are at stake, but, in my opinion, cannot be applied when there is a referral to the EBA.

There was one exception: G 1/21 on the holding of OP by ViCo. According to T 166/84 and Guidelines E-VII, 3, procedures should have been stayed whilst the EBA was deciding.

Luckily the EBA “interpreted” the questions, and in its quick decision, limited the application of its decision to the BA. However it took ages for the reasons of the reasons of the decision to be issued, one wonders why.

The decision of the EBA can be criticised. Neither Art 116 nor R 115 and 116 make a difference between OP before the first instance and before the boards of appeal. I range G 1/21 in the category “dynamic interpretation”. Neither can secondary legislation amend the EPC. Art 172(1) and Art 164(2) do not need any interpretation according to Art 31/32 VCLT.