On 22 June 2010, the English Court of Appeal handed down its judgment in yet another case involving stents in Occlutech v. AGA Medical. The appeal was dismissed with the result that AGA’s patent was held not infringed by Occlutech. The decision itself is interesting for three reasons: First, and most importantly, the decision contains an interesting and thorough discussion of the modern law of construction of patents in the UK; secondly, the decision perhaps surprisingly states that the issue of the applicability of “file wrapper estoppel” is not yet decided by UK law; finally, it is noteworthy that the panel of three judges who decided the case did not include Jacob LJ, who of course has by far the most patents experience of any of the current appeal judges. The absence of Jacob LJ on the panel looks set to be more common as the Judge begins to divide his time between his judicial function and his position as The Sir Hugh Laddie Chair and Director of the Institute of Brand and Innovation Law at University College London.

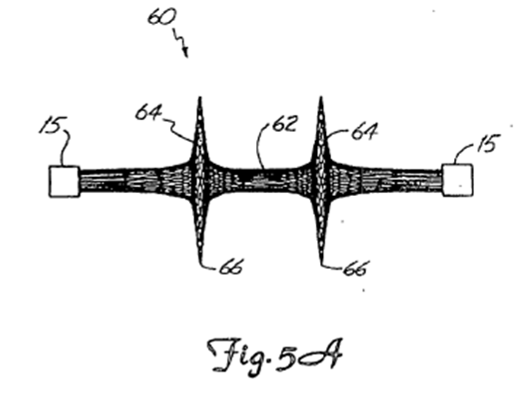

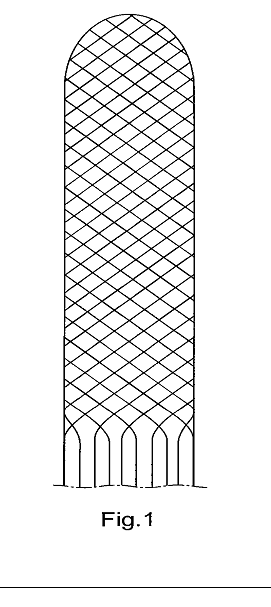

The facts of the case were relatively simple. Occlutech sought a declaration of non-infringement in respect of AGA’s patent or alternatively a declaration that the patent was obvious. At first instance, Mann J had held that the patent was valid but not infringed. Only the issue of infringement was pursued on appeal. Giving the judgment of the Court, Patten LJ stated: “the issues of alleged infringement turn almost exclusively on what is meant by “clamps” and clamping “the strands at opposed end of the device” […]. Put shortly, Occlutech says that this teaches the skilled addressee that protection is being claimed […] only in respect of a device similar in appearance to Figure 5A [of the patent] which uses clamps at both ends in order to secure the strands of braided metal so as to prevent them from unravelling.” Occlutech’s own products were made in a different (and more expensive) way using a mesh sock made out of metal wire in which there were cut strands only at one end which were secured by welding rather than by the use of an external clamp.

Figure 5A of the patent is set out below together with a depiction of the mesh sock of the alleged infringing device.

Importantly, the specification taught the use of external clamps to hold the ends of metal braiding in place and went on to state: “Alternatively, one can solder, braze, weld or otherwise affix the ends of the desired length together […] before cutting the braid…”. At first instance, Mann J placed considerable reliance on this teaching and found that the skilled reader would see that the patentee was deliberately drawing a distinction between clamps on the one hand and other methods of securing on the other. Thus the claim required an external object to exert a force on the strands of the fabric to prevent them unravelling: “clamps means clamps”.

The appeal court reached the same conclusion as the trial judge. In most respects, the legal analysis is uncontroversial. The Court started by setting out the nine principles set out by Jacob LJ in Mayne Pharma v Pharmacia Italia [2005] as modified (post-Amgen) by Pumfrey J in Haliburton v Smith [2005]. It then quoted in full the seminal passages of Lord Hoffmann in Amgen [2005], including the so-called “bedrock question”: what would the person skilled in the art have understood the patentee to be using the language of the claim to mean? The Court then noted that although the District Court of The Hague and the English Patents Court had found non-infringement, the Dusseldorf Higher Court had reached the opposite conclusion, analysing the issues according to the approach set forth in Kunstoffrohrteil [2002]. The Court of Appeal set out what it believed to be an accurate summary of the approach to equivalents in Germany and, somewhat oddly, noted that “it is immediately apparent that [the German approach] does not contain anything similar to the third of the questions posed by Hoffmann J in Improver … “Would the reader skilled in the art nevertheless have understood from the language of the claim that the patentee intended that strict compliance with the primary meaning was an essential requirement of the invention? If yes, the variant is outside the claim.” The reason why this statement is perhaps striking is that after the Amgen case and the re-statement of the law by Lord Hoffmann, most Judges and practitioners had stopped using the Improver questions as a framework to assess the issue of construction, relying instead on the “bedrock” question and the Halliburton principles to the exclusion of the three Improver questions. It is improbable that Jacob LJ would have addressed the issue in this way although, in the author’s view, he would have been likely to have reached the same conclusion.

The Court then went on to consider a point on “file wrapper estoppel” in the form of a letter to the patent office examiner which, could potentially limit the scope of the claims. Although most UK patent practitioners consider that the file wrapper cannot be taken into account in the court’s analysis of issues at trial, the Court of Appeal, relying on the Court of Appeal decision in Collag [2001], decided that the point was still open although it was not in fact pursued in this case. It is noteworthy that the Court of Appeal panel in Collag did not include Jacob LJ and perhaps, had he been part of either panel, he would have expressed the view held by most practitioners.

Having set out and discussed the relevant law, the Court finally went on to look at whether Occlutech’s devices contain “clamps” and whether the strands of the device were clamped “at opposite ends of the device”. The Court concluded that even on the slightly broader definition of “clamps” in the Oxford English Dictionary, the process of soldering or welding did not fall within the definition. The further argument was also dismissed.

This decision may be contrasted with the Court of Appeal’s decision in Ancon v ACS [2009] where the court held that a fixing that did not contain a head with a “generally elliptical cone shape” on a strict geometrical analysis nevertheless fell within the claims. It is difficult to draw many conclusions from the recent case-law although it seems that the English courts will allow more flexibility where an adjective or adverb is used in the claim rather than a noun or verb as such.

Kunstoffrohrteil [2002] G.R.U.R. 511

Improver Corp v Remington Consumer Products Ltd [1990] FSR 181

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Patent Blog, please subscribe here.