The EPO’s Boards of Appeal are famously strict on added matter. But normally applicants can sleep soundly at night after making amendments based entirely on the original dependent claims having appropriate back references, especially where the amendments still cover the examples. T 1137/21 however might cause some applicants sleepless nights, as the Board found the claims to add matter in just such a scenario, and revoked the patent.

In claim 1 of the main request, the following features in bold in the dependent claims as filed were combined:

1. A process for the post-treatment of a zeolitic material, the process comprising

(i) providing a zeolitic material, wherein the framework structure of the zeolitic material comprises YO2 and X2O3, wherein Y is a tetravalent element and X is a trivalent element;

(ii) subjecting the zeolitic material provided in (i) to a method comprising

(a) treating the zeolitic material with an aqueous solution having a pH of at most 5;

(b) treating the zeolitic material obtained from (a) with a liquid aqueous system having a pH in the range of 5.5 to 8 and a temperature of at least 75 °C;

wherein in (ii) and after (b), the zeolitic material is optionally subjected to at least one further treatment according to (a) and/or at least one further treatment according to (b);

wherein the pH of the aqueous solution according to (a) and the pH of the liquid aqueous system according to (b) is determined using a pH sensitive glass electrode.4. The process of any of claims 1 to 3, wherein in (a), the aqueous solution comprises an organic acid, preferably selected from the group consisting of oxalic acid, acetic acid, citric acid, methane sulfonic acid, and a mixture of two or more thereof, and/or comprises an inorganic acid, preferably selected from the group consisting of phosphoric acid, sulphuric acid, hydrochloric acid, nitric acid, and a mixture of two or more thereof, the inorganic acid more preferably being nitric acid.

9. The process of any of claims 1 to 8, wherein in (b), the zeolitic material is treated with the liquid aqueous system for a period in the range of from 0.5 h to 24 h, preferably from 1 h to 18 h, more preferably from 6 h to 10 h.

11. The process of any of claims 1 to 10, wherein in (b), the liquid aqueous system comprises at least 90 weight-%, preferably at least 99 weight-%, more preferably at least 99.9 weight-% water.

13. The process of any of claims 1 to 12, wherein Y is selected from the group consisting of Si, Sn, Ti, Zr, Ge and combinations of two or more thereof, Y preferably being Si, and wherein X is selected from the group consisting of Al, B, In, Ga, Fe and combinations of two or more thereof, X preferably being Al.

17. The process of any of claims 1 to 16, wherein the zeolitic material provided in (i) has a LEV, CHA, MFI, MWW, BEA framework structure, the framework structure preferably being BEA, the zeolitic material more preferably being zeolite Beta.

Although six features are combined, these are all linked through back references in the original claims. The amendment also covers the examples.

Opponent argued that there were many thousands of ways of selecting these six features from the options in the original dependent claims, and that nothing taught the skilled person to select the specific combination from the specific different levels of preference. In their defence, Patentee referred to T 1621/16 which suggests that amendments combining different levels of preference from convergent lists may be permitted where there is (inter alia) a pointer in the examples. See our discussion of this widely cited earlier decision here.

The Board wasn’t convinced by Patentee’s arguments and found added matter based on several interesting legal points.

An example covered both by more preferred and less preferred features isn’t sufficient to “point” to the less preferred features

It is a well-established principle at the EPO that a pointer in the original application to the claimed subject matter may justify an amendment, for example if the amendment still covers the examples.

However, in this case, the Board held that the fact that the examples were covered by the amended claims was not enough to support the amendments. As stated at reason 1.5:

It is true that the inventive examples still fall under claim 1 of the main request.

However, these examples are not sufficient as a pointer to the specific selection defined in claim 1 since they fall under the most preferred options of the various parameters and ranges.

This suggests that an example can’t be relied upon to provide a “pointer” to a less preferred convergent value if it also “points to” more preferred convergent values.

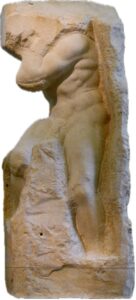

One way of visualizing this is to imagine that the specific example is a sculpture. The original claim 1 is then the original stone block from which the sculpture is made. The different levels of preference in the claims are instructions about the cuts that the sculptor can progressively make en route to the finished sculpture. But if the sculptor stops before cutting all the way for any part of the sculpture by stopping at an earlier stage of the instructions (i.e. with one or more less preferred options), different sculptures will emerge. Think of Michelangelo’s Atlas Slave for the Julius Tomb with each limb finished to a different extent.

Depending on when the sculptor decides to stop work (i.e. which of the different levels of preference to adopt), many thousands of different sculptures could have been made from the initial block of marble. Are each of these directly and unambiguously derivable from the application as filed? At reason 1.6 the Board answered this question in the negative:

While the core of the invention (e.g. as illustrated by the inventive examples) may have remained the same, the boundaries of the subject-matter to be protected have changed in a way that is not directly and unambiguously derivable from the application as originally filed, in particular in view of the large number of selections made.

For the Board, it seems that the mere fact that the slave (the example) is still buried within a sculpture resulting from finishing different limbs to different extents, does not mean that each of the great multitude of sculptures that could be made in this way are disclosed in the original instructions.

This seems to us to represent a further nuance in how “pointers” are to be understood at the EPO, which may make it more difficult to make amendments requiring multiple features from different levels of preference, even where the final claims still cover the examples.

On combining end points:

The decision also takes an interesting position on the combination of end points from different levels of preference in the originally disclosed ranges.

Under the existing EPO practice, such combinations are generally allowed. But in this case the Board found at reason 1.8.3 that combining the following end points in bold from claim 9 as filed “0.5 h to 24 h, preferably from 1 h to 18 h…” contributes to added matter since:

…by arbitrarily combining the end points, the appellant has taken claim 9… not as a list of converging alternatives but as a kind of pool of elements from which individual elements are combined. Therefore the selections made in claim 1 cannot be considered selections from a list of converging alternatives. The board notes in this regard that the appellant has not disputed the respondent’s view that the case in hand also includes selections from non-converging lists.

It isn’t entirely clear from the decision whether the combination of end points from the range would have been sufficient to lead to added matter by itself:

1) On the one hand, the Board presents the formation of the subrange as “arbitrarily combining” the end points, suggesting that the particular combination of the second least preferred option for the lower end point and the least preferred option for the upper end point may add matter. Indeed, there are many different ways of combining the six endpoints in original claim 9. How would the skilled person directly and unambiguously derive specifically this combination when the original claim language only expressly combines those at the same level of preference?

2) On the other hand, the Board highlights that other non-converging selections were needed, suggesting that the subrange may only add matter together with the other numerous amendments made.

Although the first interpretation of this decision would be controversial, it would fit with a recent trend for Boards to reexamine existing tests on disclosure, and to ignore them if they don’t fit with the gold standard (see e.g. T 1688/20 and the novelty sub-range test).

On the limits of T 1621/16:

T 1621/16 has been widely cited since it emerged, and was generally seen to be helpful for Patentees defending amendments based on multiple selections from converging lists of alternatives.

While the Board didn’t disapprove of this decision, they suggested that it may be limited to cases where there are restricted “degrees of freedom” in terms of the number of “independent directions” that amendments can go in. It is relevant here that the amendments allowed in T 1621/16 restricted a number of features relating to the components and ratios in a composition; it seems that the Board was of the view that there were only so many different aspects of this invention which could be specified. In contrast, the amendments in T 1137/21 related to different aspects of a multi-step process claim – meaning many different changes to different parts of the invention could be envisaged, see reason 1.8.3:

…while the amendments in T 1621/16 relate to the nature of the components of a four-component composition, to the weight fractions of the components and to certain relationships between the weight fractions, the case in hand relates not only to the nature of the zeolitic material to be used but also to:

– the steps of the post-treatment process and the sequences of those steps, and

– the substances to be used and the operating parameters to be respected during said process steps.

This means that possible amendments can go in more independent directions, thus increasing the number of “degrees of freedom”, and the number of possible selections and combinations of features is significantly higher than in T 1621/16.

Again, this concept of “degrees of freedom” being relevant to added matter is not something we are aware of from existing EPO case law and underlines the fact that decisions in this field are particularly case-sensitive.

On the importance of the number of possibilities for added matter

It is well established that “The number of selections and number of alternatives within each selection definitely play a role” in finding added matter (see reason 1.8.3). But normally these considerations are based on the features which were introduced into the claims. This decision seems to go one step further: concluding that the claims add matter due to the sheer number of possibilities from which the amendment was selected, the BoA also took into account the number of dependent claims not introduced into claim 1 (but left instead as dependent claims). We refer here to reason 1.4, which first summarizes all of the features introduced into claim 1, before highlighting:

In addition and by contrast, none of the options of dependent claims 2, 3, 5 to 8, 10, 12, 14 to 16 and 18 as originally filed have been inserted into claim 1.

This is also in our view a new way of approaching amendments at the EPO, and is consistent with the concept of the “degrees of freedom” discussed above.

While each decision is of course case-specific, several of the points above may be of general applicability to cases where a disclosure is based on multiple features from different levels of preference, even where these were formally disclosed in combination e.g. by cross references in the claims. It raises several interesting new points, meaning that amendments in pending cases may need to be revisited in light of this decision. Nonetheless, we hope the readers continue to sleep soundly!

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Patent Blog, please subscribe here.

I would not take such a decision as fool’s gold, in opposition the decision is made on the basis of the more convincing and better formulated arguments by the parties, if the patentee had argued better than the opponent they would have come to a different conclusion, it seems to me that the patentee just put forward his arguments in a less solid way than the opponent, especially for such a borderline and difficult to be reproduced case

In the USA, claims are considered part of the disclosure, this result would be less likely. Because claims cannot be amended after grant in the USA in court proceedings, the best practice is to include good dependent claims. In spite of this decision, that would still seem to be a preferred practice in Europe. (For example, it should be hard to argue that a patentee did not conceive of a combination that is claimed).