The EPO has proposed new amendments to the Rules of Procedure of the Boards of Appeal (RPBA) to support more ambitious timeliness objectives. In our view, they are unlikely to shorten appeal proceedings, will reduce the quality of decisions, and are unfair on Respondents so should not be adopted in full.

Background

As can be taken from Annual Report of the Boards of Appeal 2022, some progress has been made towards reducing the backlog before the EPO Boards of Appeal (BoA). Yet the objective of settling 90% of cases within 30 months is unlikely to be met anytime soon. Amendments to the RPBA have now been proposed to improve timeliness.

In our view, the EPO has correctly diagnosed itself as suffering from overly long appeal proceedings. But the proposed treatment will not treat this chronic disorder, and if anything will lead to significant side effects by reducing the quality of decisions and making the proceedings unfair. Below, we comment on the proposed Amendments which in our view should not be implemented.

Proposed amendment to Article 12(1)(c) RPBA: Default period for response to Grounds of Appeal reduced from four to two months

Article 12

Basis of appeal proceedings

(1) Appeal proceedings shall be based on

(…)

(c) in cases where there is more than one party, any written reply of the other party or parties, which shall to be filed within four two months of notification of the grounds of appeal unless the Board specifies a longer period, which shall not be more than four months;

At present, Respondents have at least four months to reply to the Grounds of Appeal. This is a challenging and time-consuming task, and the time is generally required to prepare a comprehensive response. The proposed amendment would reduce the default time for response to just two months. While the BoA can set a longer period of up to four months, which can also be extended up to six months on request and at the discretion of the BoA, it is unclear when extra time will be available. Under the amendment, Respondents can expect to have significantly less time to respond to the Grounds of Appeal.

In our view, this proposed amendment:

1) will have no meaningful impact on the timeliness of EPO appeal proceedings in the foreseeable future,

2) will reduce the quality of decisions, and

3) is unfair on Respondents.

As such, it introduces significant disadvantages without bringing any advantages.

Concerning 1), the proposed amendment would only have an impact on timeliness if the BoA dealt with files as soon as they are transferred to them such that the response to the Grounds of Appeal is the rate determining step. This is very unlikely to be the case this decade. The main delay is caused by the issuance of the preliminary opinion under Article 15(1) RPBA and any oral proceedings, which typically take place well over a year after the Response to the Grounds of Appeal has been filed.

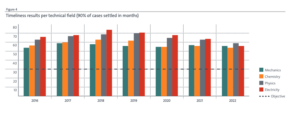

As made clear by the EPO’s own Annual Report of the Boards of Appeal 2022 page 8 figure 4 shown below, the BoA are still falling far short of their objective of settling 90% of cases within 30 months, with all technical fields still above 50 months. Based on the current trend, the objective is unlikely to be achieved this decade. Even once this target is hit, the BoA will still be far from dealing with cases immediately – they would need pendency closer to just 14 months for the Response to the Grounds of Appeal to be the rate determining step (based on the Grounds of Appeal (four months under Article 108 EPC), Response to the Grounds of Appeal (four months under Article 12(1)(c) RPBA), time until summons (two months under Article 15(1) RPBA), and time set by summons (four months under Article 15(1) RPBA)). The proposed amendment is thus unlikely to improve timeliness anytime soon.

The futility of this amendment for improving timeliness seems to be tacitly acknowledged in the “Explanatory remarks”, which do not even claim that the amendment will increase the timeliness in itself, but only that it may “support the pursuit of more ambitious timeliness objectives”. But the value in setting “more ambitious timeliness objectives” is limited when the present objectives have no realistic prospect of being met in the foreseeable future!

For 2), the proposed amendment halves Respondents’ time to reply to the Grounds of Appeal, reducing their ability to bring relevant issues to the attention of the BoA. It will clearly reduce the level of debate before the BoA and the quality of their decisions

Again, this is hard to square with the EPO’s avowed aims on quality. The “Annual Report of the Boards of Appeal 2022” starts with the President of the Boards of Appeal (PBoA) explaining that “Access to justice and rendering decisions of the highest quality is what we strive for every day – I look forward to continuing on this path!”. It also reports that the quality working group he commissioned highlighted the “completeness of the examination of relevant factual and legal issues” as a key factor determining the quality of decisions of the BoA. Why then implement an amendment to the RPBA which will clearly reduce decision quality while having no meaningful impact on timeliness anytime this decade?

Concerning 3), Appellants already have an advantage over Respondents as they can start to prepare their Grounds of Appeal after announcement of the decision in oral proceedings, typically months before the four-month Appeal period begins. The proposed amendment further tips the balance in favour of Appellants, by giving Respondents just two months to respond by default. Appellants still have four months to submit the Grounds of Appeal.

This is not only unfair but is also difficult to reconcile with several aspects of EPO law and practice.

• According to Article 23 of the RPBA, they should “not lead to a situation which would be incompatible with the spirit and purpose of the [EPC]”. The EPC stipulates that Appellants have two months just to file the formal Notice of Appeal, and four months to prepare their substantive Grounds of Appeal. The time and effort required to prepare an appeal submission is expressly recognized by and hence within the spirit of the EPC, which is incompatible with the default two-month period for responding to the Grounds of Appeal.

• A two-month period is normally only set by the EPO for issues which are “merely formal or merely of a minor character; if simple acts only are requested” (see Guidelines E-VIII, 1.2.)

• It is also contrary to the fundamental EPO principle outlined in G 9/91 that, in contentious proceedings, parties should be given “equally fair treatment”.

To balance timeliness, fairness, and quality, this amendment should not be implemented. Other options could be considered for improving timeliness, such as appointing more members of the BoA.

Finding another solution might actually also be in the EPO’s interest, since parties can now choose the forum for pan-European invalidity proceedings between the UPC and the EPO. The UPC aims to process cases more rapidly than the EPO, but the rules still give Respondents three months to respond to the Grounds of Appeal (see Rules of Procedure of the UPC 235(1)). The proposed amendment makes the EPO proceedings less attractive than UPC proceedings, by combining lengthy proceedings with shorter timelines for response.

Proposed amendment to Article 15(1) RPBA: Earliest issuance of BoA preliminary opinion just one month after response to the Grounds of Appeal

Article 15

Oral proceedings and issuing decisions

(1) Without prejudice to Rule 115, paragraph 1, EPC, the Board shall, if oral proceedings are to take place, endeavour to give at least four months’ notice of the summons. In cases where there is more than one party, the Board shall endeavour to issue the summons no earlier than two months after receipt of the written reply or replies referred to in Article 12, paragraph 1(c). A single date is fixed for the oral proceedings. In order to help concentration on essentials during the oral proceedings, the Board shall issue a communication drawing attention to matters that seem to be of particular significance for the decision to be taken. The Board may also provide a preliminary opinion. The Board shall endeavour to issue the communication at least four months in advance of the date of the oral proceedings. In cases where there is more than one party, the Board shall issue the communication no earlier than one month after receipt of the written reply or replies referred to in Article 12, paragraph 1(c).

The preliminary opinion of the BoA brings in the very strict approach to admissibility under proposed amended Article 13(2) RPBA. The proposed amendment to Article 15(1) RPBA specifies the earliest date the BoA can issue the preliminary opinion as just one month after the response to the Grounds of Appeal. This places parties under significant pressure to respond to the response to the Grounds of Appeal immediately to avoid the risk that their submissions fall under the strict admissibility requirements of Article 13(2) RPBA.

Like the proposed amendment to Article 12(1)(c) RPBA discussed above, this introduces significant disadvantages without bringing any advantages. It will have no meaningful impact on the timeliness of EPO appeal proceedings anytime soon, and will only do so once the BoA start to deal with cases immediately. It places parties to the Appeal proceedings under unnecessary pressure to make complex submissions on a very short timescale. As such, we think it will have a negative impact on the debate before the BoA and the quality of decisions.

This is exacerbated by the fact that this period starts on receipt of the reply by the BoA. This may occur several days before the parties are notified. It seems to us to be very user- unfriendly to have a time period start to run from an unknown date of receipt of a document by the EPO rather than from its notification to the parties.

In our view then, this proposed amendment also should not be implemented at least until the BoA are able to deal with cases as soon as they are transferred to them.

Conclusion

While we applaud the EPO’s desire to improve timeliness of appeal proceedings, it is unlikely that the proposed changes will deliver this goal. At the same time, they are unfair on Respondents and will decrease the quality of decisions. The EPO plans to introduce these changes on 1 January 2024, and it will be interesting to see if they change their position following the concerns raised in the User Consultation.

Based on our previous experiences of EPO User Consultations, we suspect that the patient may have some undiagnosed hearing difficulties on top of the chronic timeliness disorder. Thus, we would not be surprised to see the proposed amendments implemented despite being the wrong medicine and despite substantive criticism also by others. But we are not (yet) giving up hope.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Patent Blog, please subscribe here.

yes weird that such obligations are put on the shoulders of the respondents for solving internal workload issues, unless the BoA is now already fulfilling every strictest possible internal timeliness constraint and really needs a help from the other side to reach the 30 months target. But is this longest time duration a shared and optimal time frame? This I don’t know …

In a different blog, I expressed some opinions:

There has not been shown in the slightest that the amendments envisaged are indeed necessary. “To support the pursuit of more ambitious timeliness objectives” is not a reason sufficient to shorten the time limits at stake. Timeliness might be an important factor, but it is not the determining factor. Such a statement does not define a compelling case requiring amendment. on top of it, no figures have been provided which could justify the amendments thought.

The amendment of Art 13(2) RPBA20/21

The only amendment which is not controversial in the proposal is that of Art 13(2) RPBA20 which states that the trigger of the third level of convergence is the communication according to Art 15(1) RPBA21. The proposed amendment does not change the present situation.

The amendment of Art 12(1) RPBA20/21

Reducing ab initio, under the envisaged Art 12(1) RPBA, the time limit for replying to the statement of grounds of appeal is plainly detrimental to respondents. It will not improve the timeliness. The appellant has four months to file its statement of grounds of appeal, whereas according to the new Art 12(1) RPBA, the respondent would only have, to start with, two months. How is it possible to reduce so severely the possibility of defence of respondents?

That a request for extension of this time limit is possible, does not help either as the extension is left to the discretion to the board. When one sees how the boards apply, in a truly arbitrary way, the discretion offered to them by the RPBA20/21, such a possibility is more theoretical than practical. This is the more so, since the EBA has reiterated in R 6/20, published on 14.09.2023, that under Art112a it will not review any discretionary decision of a board.

One way of circumventing the reduced time limit would be for all parties to inter partes first instance proceedings to file an appeal. The appeal can later be withdrawn and the fee reimbursed to 75% under R 101(3). Paying for an extension of time limit can, at a pinch, be envisaged. As the EPO is apparently worried about its financial situation, cf. the proposal of increasing the IRFs for years 3-5, it would be a welcome complement.

The amendment of Art 15(1) RPBA20/21

It is difficult to see how an “early notification of a summons to oral proceedings is purely beneficial for parties and representatives, who can make the necessary arrangements”. The contrary seems true. Neither the parties nor their representatives will benefit from the change. “Necessary arrangements” will not be made easier when the time limit is shortened.

The amendment to Art 15(1) RPBA20 has for direct effect to start the application of the third level of convergence earlier. In other words, the purpose of this amendment combined with the amendment of Art 13(2) RPBA is clearly to avoid parties filing further submissions after the second level of convergence has been entered.

Final comments

The necessity of the proposed changes to the RPBA20/21 is anything but apparent. There is actually no compelling case which justifies any of the changes proposed.

Working under an exacerbated time pressure cannot be considered as being “purely beneficial for parties and representatives”. Working under an exacerbated time pressure increases the costs for the parties, but to what avail?

I would simply refer to an older say: “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it”

It will be interesting to see what the management of the boards will make with the result of the consultation. Past experiences allow the reasonable conclusion that results which are not along the envisaged line are more or less ignored or at best belittled.

When looking at the various “consultations” carried out by the EPO in recent years, one immediate conclusion would be to consider that such “consultations’” have no more reason d’être than a mere alibi function.

I have never seen any substantial amendment of what was proposed originally by the EPO after a so-called “consultation” by the EPO.

It looks more that the EPO wants to clear its conscience vis-à-vis its users, so that it can tell the Administrative Council that users have been “consulted”.

Strangely enough, the published consultations of the EPO systematically appear to support the point of view of the EPO.

The “best” thing about that all is that all technical fields are treated just the same. Where the present time limits are already oftentimes challenging, in the field of biotechnology, where one can have dozens and up to hundred documents on file, these new time limits are nothing else but a nightmare. What comes next? Maybe that the submissions of the Appellants and Respondents shall have no more than 10000 words?

Clearly, if “quality” is measured by only one yardstick (= timeliness) then the result of such measures will be that the decisions on the matter will degrade on the intellectual level. Like we can observe in examination already. The rushed examination proceedings lead to low quality patents which then lead to more oppositions which then lead to more appeals. However, the best way to “accelerate” oppositions and appeals is to have no opposition or appeal! If this requires to have another round of substantive examination, then this seems to be a very good investment.

The EPO management needs to remember that the EPO is not an “assembly line” that spits out “products”, effectively, as a patent is a right to prohibit, it is a law making institution. Rushed out laws have never been any good. However, if we do think of the EPO being an assembly line, usually, more workforce helps to produce more products in less time. There is a saying, that there is “good law”, “fast law” and “cheap law”, but you can pick only two at the same time. In the past years the EPO very often has chosen fast and cheap …

So I agree that while an acceleration of the proceedings is in principle welcome, one has to seriously think how this can be done without jeopardizing the intellectual quality of the end result. What about correlating the time limit with the number of Opponents/Appellants and the number of relevant documents in the procedure? By this way complex cases get the time they need and “simple” cases can be accelerated. Or what about providing the Boards of Appeal with sufficient workforce by appointing more members that can assemble more flexible into specific Boards?

“The EPO management needs to remember that the EPO is not an “assembly line” that spits out “products”, effectively, as a patent is a right to prohibit, it is a law making institution.”

Too true. But that rather misses the underlying point, which is that, for the EPO and its overlords, “fast” = “profitable”.

Now you may quibble that the EPO was not created in order to generate fee income purely for the sake of it. However, in the last 15 years or so, neither the EPO’s management nor the Member States appear to have perceived this as a barrier to consistently generating substantial surpluses that can be squirreled away as they see fit.

The absence of any independent, external auditing of the EPO’s accounts makes it impossible for outsiders to understand precisely what is going on, and why. In any event, the absence of any effective means of ensuring accountability makes it irrelevant whether anything untoward is happening . This is because, even if it were, there is literally nothing that any of the rest of us can do about it. Apart from, perhaps, boycotting the EPO … which seems somewhat unlikely, given the incentives that are built into the system for applicants to select the EPO when seeking protection in Europe.

The previous tenant of the 10th floor has been instrumental in disbanding the external auditors, and the AC accepted it. I would guess that the “cooperation budget” has greatly helped to arrive at this decision.

The tail has been wagging the dog since 2013-14, and it continues with the present tenant of the 10th floor.

What can you expect with such a configuration? The AC has completely given up its control function.

why should be impossible to figure out the accounts of the EPO? Salaries are known, social taxation is also known (I guess), fees can be also easily figured out based on workload, age of the proceedings, etc. and other types of costs and investments cannot be that different from similar companies or organisations: what are the factors that could change completely the picture? I don’t think there are any, if you think of some benefits or bonuses which are not made public these cannot change the result for more than a very small percentage, and I am sure there are no slush funds or the like … so I am pretty sure that any expert consultant could approximately give an estimation of the revenues and expenditures of the EPO (perhaps, plus minus 5%). And, by the way, aren’t these provided by the EPO self like by any other institution? Talking about expenditures, especially for staff, I find it strange that you all of a sudden strive for a faster or certain procedural duration without precisely planning higher investments and expenditures: so, either your plan is actually to shift the burden of this change on the shoulders of the external parties (in terms of costs, timeliness, quality, etc.) or, if not so, you should admit that you have been failing from the very beginning till now under every aspect, like effectiveness, internal process prioritisation, IT development, motivation and seriousness of your staff (at any level), understanding of the applicants needs and of the IP world, basically everything that would be expected from a good patent office

I am more or less retired, after having qualified as a patent attorney before the EPO got into its stride. I have lived through an era in which patent office practice was free of politics, and have seen politics come to dominate the administration of patent rights. Politicians go in fear of unexpected events that leave them looking indecisive, with the consequence that they lose the next election. So they are really very keen to be pro-active rather than weakly reactive, that is, they strive to “make the weather”.

The EPO President, I guess, understands how to give the politicians who “own” the EPO the weather they want, the “weather” that will make them look good.

One way to look good is to win the willy-waving competition with other patent jurisdictions around the world, notably the USA, where Europe is portrayed as effete, complacent and ineffectual. With these rule changes, AC members can ponce around the world busy declaring that they have transformed patent rights administration in Europe from “slow, soft and expensive” into “fast, direct and economical”.

Only the supra-national mega corporate users of the EPO can do anything about such trends. But do they want to? I doubt it.

Dear Max Drei,

You sound rather pessimistic. I would not be as pessimistic as you are.

I would not say that politicians are directly looking at what is going on at the EPO. The delegates to the AC are not at such a level. As long as the “cooperation” budget flows, they are not bothered.

If Art 4a EPC2000 would be applied, the situation might change. That the preceding and the present tenants of the 10th floor do not wish such a conference, which would be at the political level, does not come as surprise.

Furthermore, just have a look at what the IPQC has started. You cannot say that at least some supra-national mega corporate users are prepared to accept any waffling coming from the EPO in matters of quality. What good a patent is if in the end, it does not resist any serious challenge.

Dear Benjamin Quest

One should not forget that the main cause of the backlog at the boards was the absence of recruitment of members during the tenure of the Corsican president.

He found that the board members were much too lazy and, since he had the right of presenting candidates for the boards to the AC, he did not make use of this right.

He went as far as to compare the production at the German Federal Patent Court (BPatG) with that of the boards. By doing so, he forgot that the BPatG also deals with trademarks. When comparing what is comparable, i.e. the respective dealings with patents, there alleged discrepancy shrunk dramatically. Both institutions had comparable productions.

Your idea of taking into account the number of Opponents/Appellants and the number of relevant documents in the procedure looks interesting, but when looking at the average number of Opponents/Appellants and the number of relevant documents, your idea can easily be dismissed.

The boards have appointed lots of members in the recent years, but those have to be trained and are only progressively helping in the production.

One thing also to keep in mind, is the overrepresentation of German members in the boards. I am not in favour of national quotas for members of the boards, but according to the Annual Report 2022, 35% were German, 13% French, 11% Italian and 8% Spanish. The figures for 2021 are the same. This proportion should by no means increase.

“Rules of Procedure of the Boards of Appeal” If they are amended like the ones of the UPC, it means “No Parliament involved ™”.