It will be nothing new for regular readers of this blog that I and many others have long been advocating for more well-qualified examiners at the EPO, e.g. here. Obviously, these examiners also need to be given adequate time to scrutinize the ever-increasing number of new patent applications per year thoroughly.

Alas, it will also be no secret that the policy of the EPO upper management, unfortunately endorsed by the Administrative Council, has been exactly the opposite for the last ten years. While the number of new European Patent Applications per year increased by about 10%, i.e from 174.500 to 193.500, during the time period from 2018 to end of 2022, the number of examiners actually decreased by about 10%, i.e. from 4315 to less than 4000.

On top of this, there has been pressure on the EPO by the Administrative Council (AC) to grant as many patents per year as possible. For example, when the number of grants suddenly decreased in 2022, some AC members got quite nervous. The EPO management was urged to do something to bring the numbers up again. The result was a strong uptick of grants in the first half of 2023 at the expense of searches and communications under Art. 94(3) EPC. In other words, the EPO got in yo-yo mode.

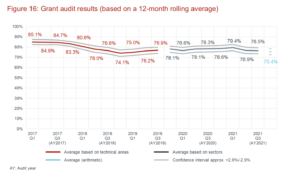

Before this backdrop, it is utterly unsurprising that the quality of European patents has suffered. Even according to the EPO’s own metrics, the grant audit results decreased from about 85% to about 75%, as is shown on the following EPO slide:

The complaints by the Industry Patent Quality Charter (IPQC) and others therefore seem to be well-founded and deserve being taken seriously.

This post, however, will deal with some (perhaps unintended and certainly undesired) side effects of the EPO management’s policy on the monetary side. Due to the fact that patents are now granted faster than in the past, the EPO meanwhile sees one of its main income streams deteriorating, i.e. the internal renewal fees due before grant. In the EPO’s own words:

For a European patent application, internal renewal fees (IRF) are due by the applicant to the EPO in respect of the third and each subsequent year, calculated from the date of filing. After grant of the European patent, and in order to maintain it, national renewal fees (NRF) are payable to the respective offices of the designated states in which the patent owner has validated the European patent. Each contracting state is competent for determining the respective level of NRFs and the EPO receives 50% of the NRF amounts.

The implementation of Early Certainty since 2014 and efficiency gains from SP2023 have led to a shift in revenue streams, as the EPO has moved away from a backlog situation to an office operating at “cruising speed”.

In other words, the EPO now earns less money than before due to its questionable staffing and quality policy.

There are two types of managers in this world. One type recognizes that a policy resulting in both less revenues and criticism by important users perhaps deserves reconsideration and reversal. The other type “doubles down” and goes full cruising speed ahead (aka the “Titanic approach”). I leave it to readers where they would position the EPO management.

In any case, there is now a (real) gap in the EPO’s revenues that must be filled up. How do you accomplish this? Very simple – just raise the renewal fees, and in particular those due in patent year 3 and 4, when the patent has not yet been granted, i.e. the EPO’s Internal Renewal Fees. Let’s assume the EPO accountants told their management that these fees should be raised by a whopping 20-25%, for example from 530 € (now) to 690 € for ordinal year 3, or from 660 € (now) to 845 € for ordinal year 4.

It is predictable that such a massive fee rise will not exactly be very popular with those who will ultimately have to pay them, i.e. the applicants. Thus, the utmost effort must be put in propaganda to make this fee rise palatable to those having to decide on it, i.e. the EPO’s Administrative Council. Let’s not rock the boat too much.

With that, you now have the appropriate background for the most innocent paper ever published by the EPO, i.e. the Non-paper on fee-related support measures for micro-entities and fee policy Non_paper_on_fee_policy_May_2023_1694250623. Would you, as a member of the AC, even bother reading it? Can anyone ever be against “fee-related support measures for micro-entities”? Surely not. Let’s go for it. Bring it on.

But let’s assume, as our fallback position no. 1, that the members of the Administrative Council (and the public) at least bother reading the Introduction of this “Non-paper” to find out what it is exactly about, although they are quite busy people. In this case, paragraph 1 of the introduction will educate them how great and how important SMEs are for the European economy. Well and good. Readers will further understand from paragraph 2 that times are difficult, particularly for SMEs, due to the past pandemic, supply chain issues, the Russian aggression war against Ukraine, and inflation. Probably heard that before, but certainly true or at least plausible.

The third paragraph then starts with

Against this background, the EPO is committed to further enhancing the attractiveness of the European patent system by making it even more accessible for innovative smaller entities.

Yes, great. Who would ever expect a fee rise lurking behind such noble intentions? The thing is, though, that micro entities (i.e. companies having <10 employees and ≤ EUR 2m turnover or balance sheet sum, no subsidiary or owned by larger enterprise) only file a very small percentage of all European patent applications, which is understandable when considering how expensive patents still are and that you should better have made a patentable invention to begin with. Thus, the proposed measures will fortunately not be overly costly for the EPO. Nonetheless, a good idea, which deserves being explained in more detail:

To achieve this goal, this paper considers new fee-related measures well beyond those already in place. More specifically, the EPO intends to provide further support for these entities by means of dedicated fee reductions, targeting in particular innovative companies with little experience of the European patent system. It is intended to increase the current financial support by a factor of four.

Furthermore, in line with the overall objective, a simplification of the fee structure is proposed in order to reduce bureaucracy and complexity, while at the same time seizing the opportunity to create incentives for the digitalisation of processes.

Also, the inflation adjustment step of 5% in 2024 as provisionally foreseen in CA/50/22, equivalent to EUR 75m of further income, will not be realised. Instead, it is proposed to have a targeted increase of certain procedural fees and the internal renewal fees (IRFs), which would also fund the proposed support measures, while at the same time addressing recent trends and developments, which are mainly due to the improvement of timeliness at the EPO

Thus, just a “targeted increase” of “certain” procedural and internal renewal fees is proposed to “also fund the proposed support measures”.

You have to melt this on your tongue.

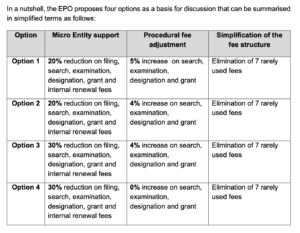

Yet this targeted increase of certain fees is not even the highlight of this master piece of introduction. The highlight is the table at the end of this chapter, reproduced here.

Looks great, does it not? Micro-entities profit a lot, certain procedural fees are increased (but only by 4-5%, which is well within the range of the current inflation rate), and the fee structure is simplified by elimination of 7 rarely used fees. Fantastic proposal. You can stop here and vote in favour.

Or you read further – which would be fallback position no. 2 – assuming you are a more thorough reader. In this case, you would still have to dig through pages 5-8, which basically tell you the same story again in even greater detail, until you reach Chapter 5 “Financing measure”. And even this chapter starts with a proposal not to pursue a general inflation adjustment for 2024. It gets ever better for applicants. Who can be against that?

Only on page 9 of this non-paper an account is given on the EPO’s losses by its “Speed über alles” policy. A typical case is presented, assuming that the patent is now granted in year 5 rather than in year 6 as in the past. This results in a decrease of income of EUR 970 per patent for the EPO. Hmm. Poor EPO. So, what to do about it?

Chapter 5.2 does of course not call it “Fee increase”; it rather proposes a “Linear progression of IRF annuities”. Splendid idea, for who on earth would ever support an quadratic or even exponential progression of such fees? That would sound so greedy. But linear is good, and thus the non-paper is a prime example of modesty and altruism. Here we go:

It is therefore proposed to adopt a linear progression of IRFs. The proposed IRF fees (see ANNEX 4) reach the same amount for ordinal years 10-20 as today and follow a linear progression until year 10.

The strongest change compared to the IRF of 1 April 2023 would be for ordinal years three to five.

Thus, readers are politely referred to the annexes (our fallback position no. 3), of which only the very last one contains the actual figures proposed. The figures (reflecting a 20-25% fee increase, if you do the maths) are indeed there, but carefully embedded between the words “Option”, “Discount” and a graph that on the face of it suggests that everything stays more or less within the present ranges. You really have to look very closely to the actual figures and the text (fallback position 4) until you realize what this non-paper is actually about: a massive increase of the EPO’s Internal Renewal Fees.

At the end of the day, the EPO has been so “successful” in examining patent applications with “cruising speed” that it now wants more money for lower quality work. This should be a no brainer.

I have occasionally compared the European Patent Organisation with the Holy Roman Empire of German Nation, and the EPO President with Emperor Maximilian I. Another highly interesting parallel between the two is the skillful and abundant use of propaganda. Maximilian I. lived at a time when Guttenberg had just invented the printing press and was one of the first rulers who had recognised the propagandistic possibilities of printing, which was expanding with new forms of design; he promoted woodcut and typography and employed the finest woodcutters of his time for that (source: wikipedia). He wrote (or had written) two books, Theuerdank (literally: expensive thanks) and Weißkunig (white king), reporting on his heroic deeds in the form of a high medieval epic, which was illustrated lavishly.

In particular, Theuerdank presented a legend of his own person, who masters all dangers prudently, wisely and bravely. His adversaries Fürwitz, Unfall and Neidhard represent allegories of three vices: wantonness, greed for glory and envy. With them as adversaries, Maximilian succeeded in establishing a myth, a melange of fiction and reality that illustrated his position as victor. It is worth reading the Wikipedia entries on Maximilian and Theuerdank in detail – you may discover even more parallels. Then, re-read the EPO’s glossy reports on how heroically the President has improved or is about to improve quality, and you know what I mean. The current non-paper on fee-related support measures for micro-entities and fee policy, a masterpiece of deflection and spin, certainly stands out among these propagandistic measures. The myth of President Robin giving to the poor and taking from the rich (applicants) is all over the place, whereas you need a while before you realize who is actually taking the money from your company and why.

Just to be clear: your money will mainly go to a quasi-autonomous international organisation that is so wealthy that it had no apparent problems to absorb “2.1 billion EUR losses in assets following the deterioration of the financial markets in 2022” (because it is heavily invested in these markets) and a “1.2 billion EUR increase in liabilities” last year (source: EPO Annual Report 2022). Or, perhaps, it did or does have problems and the proposed fee increase is part of the solution. Honi soit qui mal y pense.

_____________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Patent Blog, please subscribe here.

Kluwer IP Law

The 2022 Future Ready Lawyer survey showed that 79% of lawyers think that the importance of legal technology will increase for next year. With Kluwer IP Law you can navigate the increasingly global practice of IP law with specialized, local and cross-border information and tools from every preferred location. Are you, as an IP professional, ready for the future?

Learn how Kluwer IP Law can support you.

This article may be of interest:

https://www.patentlitigation.ch/productivity-vs-quality-at-the-epo-a-rare-glimpse-behind-the-curtain-thats-worrying/

Sustainability (financially only) is the key. No changes are to be expected after the latest ILOAT judgments. The new career system will remain in place whatever the consequences are.

Simplification of the fee structure? The proposal seems overly complicated, and the result even more… It does not seem to be a “simplification” at all…

Thanks to Mr Bausch for an entertaining but revealing paper on the doings of the EPO.

The EPO has indeed become a master in propaganda and most of its publications have to be taken, not with a pinch of salt, but a whole vat of it. Just look at the very verbose Quality Charter published a year ago. If all what is described therein would correspond to reality, there would be no need for the users of the system to complain about the quality of the work delivered by the EPO, cf. IPQC.

The same applies to the Quality report 2022. Whilst on page 38 it is clear that searches without any finding have gone down about 10% from 2021 (92,3%) to 2022 (82,6%), there is no explanation found about this lowering of the quality of searches. In the diagram on page 38, there is a heading “quality improvement” which increased from 3,3% in 2021 to 9,7% in 2022. The corresponding explanation, granularity of the extended search audit, is anything but convincing. This does not hinder the EPO to claim “that the overall very high level of quality of search reports was maintained”

The same applies to the quality of examination, see page 46 of the QR 2022. It has changed from 75,4% in 2021to 76,6% in 2022, in spite of all the measures having allegedly been taken to improve quality of examination.

It does thus not come as a surprise the non-paper at stake here, is of the same kind: hiding reality behind smoke screens.

Before going into more details, it should be reminded that it was Mrs Brimelow which decided that the financial situation should be dealt with according to the IFRS financial rules. This meant that the procedural fees like search, examination, opposition and the like, whilst on the EPO accounts, should not be counted as income, unless the work was carried out. This was not a bad move, as it allowed to clarify the financial situation of the EPO, which by the way has never been bad.

‘When deciding to reduce salaries and benefits for staff, the actual tenant of the 10th floor decided that the annual fees revenues should not be taken into account, and even went as far as to consider that for the years 2018 to 2038, the income would not increase and remain constant, whereas the salaries and pensions will grow at a rate of 2,24% above inflation. I speak here about the famous 2019 Mercer and Wyman study.

In 2019, the Central Staff Committee commented as follows:

– between 2018 and 2038 the EPO will not raise its procedural and renewal fees except once, by 4%, in 2020. For the remaining period the fees are assumed to remain constant (page 115). A correction for inflation is not foreseen.

– between 2018 and 2038 the national renewal fees on patents granted by the Office will remain constant (page 116). A correction for inflation is not foreseen.

in sharp contrast during the same period EPO salaries are assumed to increase at a rate of 2.24% above inflation (page 119).

– without providing any underlying data, the study assumes that the costs of pensions and other post-employment benefits (incl. tax compensation) will almost triple over the next 20 years (pages 66-67, page 123).

– The study foresees no further transfer of operational surpluses to the RFPSS, although with a 4.8% return above inflation over the last 20 years (6.3% over the last 5 years) the money would be well placed (RFPSS/SB 41/19, page 2, Fig. 3).

the study assumes that operational surpluses will not be transferred to the EPOTIF either (page 63). The EPOTIF was recently created with the very purpose of shielding EPO capital from inflation and is expected to deliver a return of 4% above inflation (CA/F 10/18 para.10).

– instead expected operational surpluses are assumed to be parked as “other financial assets” with an average annual return of between – 0.03% and 0.78%, i.e. well below the level of inflation2.

– as indicated above, over the last 20 years the RFPSS had a real return of 4.8%. The actuaries who evaluate the RFPSS assume a long-term return of 3.5%. The Financial Study assumes a return above inflation of only 2.1% (FAQs). This transforms today’s 104% coverage (CA/61/17 point 79) into a 2 billion euro gap in 2038.

The 2019 EPO Financial Study by Mercer and Oliver Wyman assumes that:

‘”Although the EPO’s currently makes a budget surplus of about €400m /year (20% of the budget), Mercer and Wyman predict an overall €3.8bn deficit by 2038 and endorse the President’s suggestion to add a €1.9-2bn “buffer” when closing the alleged gap. The principal means planned to fill the alleged gap will be a reform of the annual adjustment method for the staff’s salaries and pensions.”

‘SUPO asked Ernst and Young to check the Mercer and Wyman study, with the following result:

Ernst & Young estimated what they called the “illustrative impact” of those highly conservative assumptions. Their main findings are the following:

– more realistic assumptions (in line with those of the RFPPS actuaries) for the contribution levels to the RFPSS and the EPOTIF reduce the alleged gap by €2.3bn

– more realistic assumptions of the return on the RFPPS and EPOTIF assets in line with other EPO documents reduce the gap by €4.0bn,

– taking into account expected future income from patents existing in 2038 (omitted in the 2019 study) reduces the alleged gap by €4.7bn,

– assuming that EPO internal fees will rise with inflation (rather than stay constant until 2038) reduces the gap by €1.6bn.

– Ernst & Young further pointed out a methodological error in the 2019 study that inflates the gap by €1.3bn.

If now allegedly there are problems, it seems that the upper management has, in spite of its very “conservative” approach, manifestly failed and completely misjudged the situation.

I would therefore expect that not only the IRFs will be increased, but the next attack on salaries and pensions is programmed. The last salary increase resulting from the “new adjustment method”, which was clearly not favourable for staff, was so high that some delegations in the AC chocked on it.

SMEs are the fig leaf behind which the proponents of the UPC have been hiding to push it through. As it worked so well for the UPC, it does not come as a surprise that the upper management of the EPO has jumped on this train.

The package is so well presented that a reader with normal attention will not realise what is going on. It is thanks to people like Mr Bausch that we are made aware of the truth behind all this waffling prose. I would therefore be inclined to share Mr Bausch’s suspicion: there are problems, most probably linked with EPOTIF due to the gambling with the money of this fund, as the RFPSS is much more controlled.

* Fill in the gap!

Is the EPO’s financial position really so precarious that they have no choice but to increase (by huge percentages) fees paid by essentially all applicants?

Even though the last financial study was based upon an assumption of no fee increases whatsoever that study did not predict financial doom for the EPO in all scenarios. Since that study was completed, the EPO’s financial performance (relative to predictions) will no doubt have been boosted by:

(a) at least two rounds of increases, including an exceptional, out-of-turn increase to account for an unexpectedly high rate of inflation; and

(b) steps taken by the EPO to reduce (increases in) their wage bill, for example by reducing examiner / formality officer numbers, and greatly limiting salary increases / rewards for the majority of employees.

Indeed, if I am not mistaken, has the EPO not made very substantial surpluses each year since the last financial study … so much so that they have been able to transfer huge sums to (relatively) “risky” investment portfolios?

Of course, there is no independent, external audit of the EPO’s finances, and so it is difficult to know precisely what is going on behind the scenes. Nevertheless, the EPO’s pronouncements on the reasons for the proposed increases are impossible to square with a few facts that can be established. To me, this disconnect between reality and the EPO’s pronouncements makes the latter not so much a masterclass in propaganda as tour de force in gaslighting.

Mr Bausch you have no idea how much we older examiners admire you for digging out the sh!t under the shiny surface carefully built by our incompetent leaders.

It reminds us of the good old times when we actually had the time to do our work and dig out the same material from applications, which now result almost immediately in very shiny, smelly, worthless – and as you just discovered – more expensive and less profitable granted patents.

Sorry but now it is not the right time to disturb us: this week there will be an apotheosis of BS events at the office. Have a look in the Internet, maybe you’ll find them as well.

EPO and UPC are self-financed institutions, which feed themselves on the number of granted patents and number of litigated patents respectively. What could go wrong? Are they still public institutions we can trust?

Furthermore, they are govern by law makers which have a strong conflict of interests, as they receive renewal fees from those granted patents.

I find it normal that if you get a grant in shorter time and you pay less fees because of this an increase of fees per year be taken in consideration, it would be only fair and of common sense. At the same quality of course! I personally doubt that the internal auditing department of the EPO is consistent, reliable and has a better quality understanding than the rest of the examiners, in industry it is usually only a different career opportunity which is very often quite detached from the real work. Quality can be determined only by studying real cases with respect to past cases and this can be done only together among applicants and EPO experts by analyzing specific cases, all the rest is only fresh air, still waiting for the jointly agreed publication of a striking case that exemplarily describes a quality deterioration …

Something further has struck me about the EPO’s reasons for proposing (significant) increases in the renewal fees for years 3 to 5. That is, the reasoning is entirely focused upon perceived “losses” to the EPO regarding income generated from (internal) RENEWAL fees.

This reasoning is particularly odd because it is entirely divorced from the EPO’s obligation under Art 42 EPC to ensure that the budget of the Organisation is BALANCED.

The EPO has made no attempt to demonstrate that the “losses” (of income from internal renewal fees) in any way threaten to throw the budget of the Organisation out of balance. Indeed, it is perfectly possible, perhaps even highly likely, that the proposed increases in renewal fees are NOT required to keep the Organisation’s budget in balance.

Absent any demonstration of a clear and present danger to the “balance” of the EPO’s budget, I really do not see how any AC members could possibly justify voting for the EPO’s proposal.

@ Concerned observer,

As long as the “cooperation budget“ will be used to „help” the votes in the AC, any proposal stemming from the 10th floor will be rubber stamped by the AC.

It is only if weighted voting is introduced for all decisions, that we can expect some improvement of the situation.

One country, one vote has been fatal to the EPO as it has become fatal to the EU.

Just an example: when it was decided to ban the boards of appeal to Haar, the large countries voted against, but a simple majority was achieved with the help of the cooperation budget. Now without batting an eyelid, the boards will be repatriated to one of the empty EPO buildings. The million of € dilapidated by those successive moves will have been spent in vain

Do not expect to get anything positive from the AC. As as been said by others, the tail is wagging the dog. The AC has given up his control function of the EPO. Sad but true.

weird that EPO employees pled for years for fee increases to maintain their high salaries or low efficiency and now they oppose this only because it may be a sign of weaker finances and thus of a need of possible internal staff reforms, or only for the sake of saying no …

@law sniffer,

You have amply demonstrated here and in previous blogs that you have strong reservations about examiners at the EPO. One wonders why.

You seem either to belong to the upper management of the EPO or to be a staunch supporter of the latter.

In order to see how the quality of the work delivered is not what it used to be, I invite you to look at decisions of the boards of appeal, especially after an opposition.

As oppositions are not evenly distributed over the whole technical domains, their result should not be over interpreted, but their number is high enough to be revealing of the present loss of quality over the years.

To be blamed are prima facie not the examiners, but the upper management of the EPO.

Internal staff reforms are been carried out for many years, up to the point that the EPO is not any longer the employer it used to be as salaries and working conditions have been lowered to the point of the EPO has difficulties in recruiting good people.

This is compounded by the fact that training has been reduced, experienced examiners are leaving as soon as they can, but production targets are constantly increasing on the pretext that IT tools are constantly improved, which is, alas, not the case.

The remaining examiners are not stupid, they know how to play with the system, and they cannot be blamed for this. EPO’s management has forgotten that examiners have in principle the same level of education than the management. The concentration of grey cells per square meter is probably one of the highest in the world. That the result is so bad is thus mainly caused by the quest of the upper management of the EPO for ever increasing financial gains for themselves.

Sniffer, I have been working on EP patents for over two decades but have never heard of EPO employees pleading for increases in fees to pay for increases in their salaries. Perhaps you have some (non-public) insight on this matter from EPO insiders?

In any event, I should point out that the past (alleged) behaviour of EPO employees is absolutely irrelevant to the question of whether the current, proposed fee increases are justified.

For the sake of completeness, I should also point out that the blog post neither mentions EPO employees nor presents matters from their point of view. I therefore find it curious that you were nevertheless motivated to make unflattering allegations about those employees. What is it that you have against them?

I forgot to add: “maintain low efficiency” is a very subjective way in which to view the past performance of EPO employees. Another way that said performance could be viewed is “maintain high quality”. It all depends upon how one defines, and then measures, “efficiency” and “quality”. I guess that we will all have our own views on such matters.

I have had another thought that connects with my previous comments. That is, whilst a shorter average duration from filing to grant leads to the EPO recouping fewer (internal) renewal fees, that is FAR from the whole story with respect to the average fee income that the EPO recoups from each application.

Quicker grant could mean (and, looking at recent statistics, DOES mean) that the average amount of examiner time spent on each file has gone down. For the same examination fee. This represents an “efficiency” saving for the EPO.

Then there is the question of whether quicker, more “efficient” examination leads to a higher percentage of cases proceeding to grant. Looking at recent statistics, the answer to this question is a very clear “YES”. This means that the EPO will:

– reduce the number of cases in which a very significant amount of examiner time is spent on (conducting oral proceedings and) drawing up a decision to refuse an application; and

– increase the number of cases where applicants pay the fees for grant.

From the above, it will be clear that the OVERALL financial effects of an office operating at “cruising speed” may not be quite what the EPO makes out … and may, in fact, lead to the office generating, on average, MORE income per application.

This is why it is meaningless to only look at income from renewal fees, as it could easily paint a misleading picture … which was perhaps the intention?