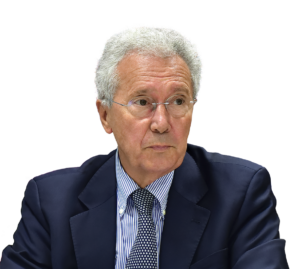

The story of the creation of the Unitary Patent and the Unified Patent Court was like the game ‘Fortunately, unfortunately’, according to Pierre Véron. The French patent litigation specialist was the founder and first president of the European Patent Lawyers Association (from 2001) and has been involved in the creation of the Unitary Patent Package from the very beginning. Less than four months before the launch of the new system, Kluwer IP Law interviewed Véron and asked him how it all started.

‘As EPLAW we met with the European Commission many times during the decade 2000-2010. The Commission considered the creation of a patent covering the whole of EU as one of its highest priorities. In 2007, I was appointed as the French expert patent litigator to assist the Commission in the drafting of what became the Unified Patent Court Agreement, signed in Brussels on 19 February 2013. Later, during the decade 2010-2020, I was a member of the drafting committee of the Rules of Procedure of the new court. In that period I was also heard by the European Parliament on the future European patent litigation system.

It was a very exciting experience to build a new international court without any model or precedent.’

What issues were debated most at the time?

What issues were debated most at the time?

‘During the decade 2000-2010, the main issue was what institutional framework would be the most appropriate. There was a certain competition between the EU Commission, which favoured the creation of a court within the European Court of Justice, and the European Patent Office, which pushed for the so-called European Patent Litigation Agreement (EPLA) between the countries of the European Patent Convention. Eventually, the UPC Agreement was neither one nor the other.’

Did you expect the process of creation of the Unitary Patent and the Unified Patent Court system would take so long? And have you ever had concerns that the project would fail?

‘To kill the time during their long travels by car, some families play to the game “Fortunately, unfortunately”, where each player adds a new sentence to a story, starting by “Fortunately”, then by “Unfortunately”. “John was in an airplane. Unfortunately, the motor exploded. Fortunately, there was a parachute in the airplane. Unfortunately, there was a hole in the parachute. Fortunately, there was a haystack on the ground. Unfortunately, there was a pitchfork in the haystack, etc.”

This has been more or less the story of the Unified Patent Court: fortunately, a draft agreement was reached between a number of EPC countries; unfortunately, an ECJ opinion stated that it was not possible to embark non-EU countries; fortunately, another draft agreement was signed between only EU countries; unfortunately it was attacked before the German Bundesverfassungsgericht; fortunately this court rejected the recourse; unfortunately, another recourse was lodged; fortunately, it was also rejected and so on.’

Are you satisfied about the system as it has turned out?

‘A lawyer is never satisfied by a new legal system that he has not designed himself in all details! However, I feel this system is the best possible compromise between often opposite demands of stakeholders.’

What are issues in the new system that you are disappointed about?

‘My main regret is that the new system will not cover all European countries: the ECJ opinion has not accepted EPC non-EU countries (like Switzerland, or Norway), the Brexit has deprived us of the UK judges and practitioners, and Spain and Poland are very unlikely to join.’

Spain has always objected to the language regime. Have alternatives, such as an English-only system or a system with more official languages ever been a serious option?

‘An English-only system was politically impossible. The current language regime is as open as possible: in each local or regional division, the language of the country where it seats will be an option (in addition to English, in most cases). In fact, the Spanish language objection was not about the court’s language regime. Rather, it was about the EPO’s language regime, as Spain has never accepted that Spanish is not one of the official languages of the EPO.’

Why are the creation of the Unitary Patent and the Unified Patent Court so important, in your view?

‘Because it creates the so-called European Patent with Unitary Effect, best known as Unitary Patent, which is really a genuine European Patent, valid for all the participating EU Member States, rather than a bundle of national patents. And above all, because it creates a court where you can litigate in one single case the validity and infringement of a patent for the whole of Europe, instead of being obliged to start parallel actions in various jurisdiction.’

A completely new UPCA, Unitary Patent Regulations and Rules of Procedure were designed (of which a final trilingual version is available on Pierre Veron’s website). Isn’t it a leap in the dark? Are you concerned unforeseen issues will come to the surface and lead to legal uncertainty?

‘The Rules of Procedure have been discussed between seasoned experts in patent litigation and civil proceedings during dozens of meetings. More than 18 drafts were prepared and made available for comments (110 were received in writing). On 26 November 2014, a one-day meeting in Trier gathered more than 100 representatives of the interested circles to comment on the latest draft. There will certainly be unforeseen issues (by way of example, in 2014, holding certain oral hearings by video conference was not felt as a priority, whilst it proved to be one during the peak of the pandemic).’

Do you expect the foundations of the system, for instance the solutions to the withdrawal of the UK from the project as a consequence of the Brexit (no London central division branch), will be challenged before the UPC and/or CJEU?

‘Experience has proven that, about this new court, whatever may be challenged in EU courts or constitutional courts will be challenged. But I am rather confident on the outcome of any challenge based on the eventual location of the section of the Central Division which was planned to be based in London.’

A general view seems to be that Germany will have much influence on (the jurisprudence of) the UPC. Do you agree? What will the role of France be?

‘Germany is the largest EU country, at least for patent litigation. It has attracted a large volume of litigation. It is not surprising that it has some influence on the functioning of the new court. But France will host the seat of the Court of First Instance in Paris and will certainly also exert a great influence.’

You have co-organized several UPC mock trials to get familiar with the rules and procedures of the new court, most recently last November. Did any surprises come to the surface, such as unresolved issues about the interpretation of the new UPC rules?

‘I have been indeed involved in the design or in the conduct of four mock trials organized in Paris by the Union pour la Juridiction unifiée du brevet (UJUB), Union for the UPC, a French association created by all the interested circles in France. The last one took place on 21 November 2022. The script of these four mock trials were carefully designed to highlight some difficult problems in the UPC Agreement or in the Rules of Procedure (documents and video recordings are available here). There are still unresolved issues about the interpretation of the new UPC Rules of Procedure, but they do not exceed what can be expected of any new court system.’

What (else) did you learn from the recent mock trial?

‘Everyone noticed the enthusiasm of the participants – judges or representatives (lawyers and patent attorneys) for the new system.’

Is there anything else I should have asked or you’d like to mention?

‘The Unified Patent Court will start its operations court on the 1st of June 2023: see you in court then!’

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Patent Blog, please subscribe here.

“The current language regime is as open as possible”: in invalidity actions you cannot even use the three EPO languages, which you can use in oppositions and appeals at the EPO!

The UPC language regime seems to be tailor-made for French and German firms.

I don’t see any particular reason why there should not be a simple legal adjustment that would allow patentees with validated European patents in the UK, Switzerland, Noway, Spain etc to “OPT–IN” to jurisdiction of the UPC. As far as I can see, such Opting-IN to the UPC would present numerous advantages.

“ Rather, it was about the EPO’s language regime, as Spain has never accepted that Spanish is not one of the official languages of the EPO.’”

?

To my best knowledge, Spain is an EPC state and we such accepts that the language of proceedings in proceedings before the EPO is one of only three, but not including Spanish. …

English is also a difficult language: ask any person that is not well informed what a “unified” court for “European patents” could mean: nobody would guess that that only cover 13 states at the start and that it will vary over time… let alone that someone could guess which those states are…

“The Unified Patent Court will start its operations court on the 1st of June 2023: see you in court then!’”

There is a chance that the declaration of entry into force might be challenged in Court as soon as the 1st of March.

Me Véron’s plea for the UPC deserves some comments – Part 1

Brief historical review – Is the UP/UPC an absolute necessity?

Me Véron starts the history of the UPC around 2007. It has a much older history.

From the early days of the EU, or European Community as it was called at the time, patents were considered as a possible hindrance to the free movement of goods within the EC. The idea of regulating the patent system at Community level emerged quite early. In the 1960’s there were no less than four drafts for a European Patent Convention.

Those attempts faced a series of problems. First, they were all closed conventions, i.e. only open to EC contracting states. Second, the language problem was important as an official act of the community has to be published in all the official languages of the member states in order to take effect. Third, the fear of forum shopping was also seen as big threat by patent holders. At the time the UK already played a role as it was never in favour of the Community Patent.

On the other hand the patent have not become a hindrance to free trade in the EC or the EU thanks an important decision of the CJEU: the doctrine of exhaustion of rights.

It is the upcoming of the PCT which pushed some member states to revive the negotiations on an EC/EU patent. They feared being inundated by unexamined patents coming in through the PCT route which at the time consisted mainly of a search and publication as provided for in Chapter 1 of the PCT. There are still some PCT/EPC member states refusing the PCT direct route.

The solution to the problems faced by the EC/EU patent was to divide the procedure in two parts. One convention would deal with search/examination/grant/opposition and a second with the exploitation of the so granted right.

The first convention was the EPC as we know it today. The EPC is an open convention and the procedure is limited to three official languages GB, DE, FR.

Following the signature of the EPC, negotiations for a common use of the title granted by the EPO continued and a conference of a “Common Patent” was held in Luxemburg in 1975.

In principle, the conference should have led to a Community patent with unitary effect in all EU Member States.

The Convention was never signed and/or ratified as two problems remained: forum shopping and languages

Special Bodies” should also be set up within the EPO, see Art 142-149 EPC and a “Select Committee” of the EPO Administrative Council should be created. Those are now active with the upcoming UP/UPC.

In the meantime, the Contracting States of the EPO set up a Working Party on Litigation with the aim of creating a European Patent Litigation Agreement (EPLA). This was again an open convention, which was not limited to EU contracting states.

This initiative ended with two proposals

– A proposal to set up a European Patent Court (comprising a Court of First

Instance, with a Central Division and a number of Regional Divisions, as well as a Court of Appeal) with jurisdiction to deal with infringement and revocation actions concerning European patents. Do you note the resemblance?

– A proposal to entrust the European Patent Court of Appeal (acting as

“Facultative Advisory Council”) with the task of delivering, upon request, nonbinding opinions on any point of law concerning European or harmonised national patent law to national courts trying infringement and validity actions.

We all know that opinion C 1/09 brought an end to those efforts. And from then on the UP/UPC system as we know it presently came up.

It remains that for more than 40 years there was no problem with patents within the EU due to the doctrine of exhaustion of rights. On the other hand the number of validations of granted European patents was around 3-5 (UPC states), at best 7(UPC + EPC states).

It raises thus the question of the necessity of a system like the UP/UPC. This is the more so since the number of true supra-national litigations is rather low. An economic study justifying the existence of the UP/UPC has never been carried out. It is a mere allegation of the supporters of the UP/UPC system that it would be beneficial to European Industry in general and European SMEs in particular.

When listening to some conferences on the UPC at the end of the year, one could get the feeling that the UP/UPC is the 7th world marvel and that it should always have been like it will be with the UPC (cf. Business Europe). This is forgetting that the idea is an old one and the EU has lived happily without such a system. Wanting to imitate the US might not be the most convincing reason.

Dear DXT,

I fully agree with you.

Just one question as you mention Art. 142 EPC (“…may provide that a European patent may * only * be granted jointly in respect of all those States.”): does Art. 142(1) EPC allow the choice between a multiple designation (unitary patent) and single designations (UPC national validations)?

It seems to me that Art. 142 EPC does not allow said choice, like e.g. Switzerland cannot designated without Liechtenstein.

Thank you

Dear Patent Robot,

The legal framework for the UP was part of the EPC 1973 and has not been amended in the EPC 2000. The reasons for this was that, in spite of split between grant and use of the title, it was important to leave open the possibility for a common patent for the EC/EU contracting states, hence the Luxembourg conference of 1975.

The common designation of Switzerland and Lichtenstein results from a Treaty between the Swiss Confederation and the Principality of Liechtenstein on Patent Protection (Patent Treaty) of 22 December 1978. See OJ 1980. 407. The joint designation Switzerland/Lichtenstein is possible under Art 142+149. Art 3 of the treaty mentions Art 149.EPC.

I am of the opinion that a common designation is only possible under Art 142 + Art 149 EPC. A common designation of all EU/EPC member states would have required a treaty binding all EU/EPC member states. Only then a patent granted by the EPO would have become a UP for all EU member states.

As it was clear from the beginning of the renewed efforts for an EC/EU patent, i.e. a UP that not all EU member states were wanting to participate, it was only possible to resort to an “enhanced cooperation”. This is why we have a foot note under Art 142 EPC and not under Art 149EPC.

At filing all EPC member states are designated, cf. Art 79(1)epc. However, an applicant can, up to grant, withdraw any designation of an EPC member state, cf. Art 79(3) EPC.

If an applicant withdraws the designation before grant of one of the UPCA contracting states, which he is free to do, a granted EP cannot have a unitary effect. But he will still have to opt-out from the UPC during the transitional period. This does not appear very logical.

I am therefore inclined to say that Art. 142(1) EPC does, in principle not allow the choice between a multiple designation (unitary patent) and single designations (UPC national validations).

On the other hand, if one designation of a UPCA member state is removed under Art 79(3) EPC, then there is no unitary effect and single designations should be perfectly possible.

There is a further open issue to mention.

A unitary effect is only possible if there the claim set is identical for all UPCA member states. The question of national prior rights for UPCA contracting states is thus also very important during the examination phase. Without going much into detail a similar situation can occur in the presence of a national prior art in one of the UPCA member states.

According to the Guidelines G-IV, 6, where a national right of an earlier date exists in a contracting state designated in the application, there are several possibilities of amendment open to the applicant:

First, that designation may be withdrawn from the application for the contracting state of the national right of earlier date, see above.

Second, for such state, the applicant may file claims which are different from the claims for the other designated states (see H‑II, 3.3 and H‑III, 4.4).

Third, the applicant can limit the existing set of claims in such a manner that the national right of earlier date is no longer relevant.

By requesting a different set of claims in order to take into account a national prior right in a UPC member state, no unitary effect can be requested and single designations should also be perfectly possible.

It will be interesting to see what the UPC will have to say on those two topics.

There are many further open issues, but this would go far here.

Me Véron’s plea for the UPC deserves some comments – Part 2

The opening of the UPC to non-EU contracting states

This is a no go in view of the opinion C 1/09. Supporters of the UP/UPC have written lots of pleas why for instance the UK could stay in the system. Brexit put an end to these hopes.

It is also not sure that the authorities in, for instance, UK, Switzerland and Norway, would agree with such an Opt-In possibility. As they are not EU members, it would also pose a lot of problems with respect of state liability etc.

In any case, it would need a renegotiation of the UPCA. When one sees that even the consequences of Brexit have not lead to a renegotiation of the UPC, an opt-in appears no more as wishful thinking.

Languages

It all depends what one understands under “The current language regime is as open as possible”.

Whether the language regime during the transitional period is in conformity with the London Protocol on translations remains to be seen.

It is only before the Central division that the language of proceedings will be that in which the patent has been granted. Before a local division it is not necessarily the case and it could well be the local language.

Me Véron is alluding to Rule 14.2(c), which is called the “English limited clause”. It allows for litigation in an EPO language, especially English, while at the same time allowing for issuing the judgment in the national language.

When looking at the language regimen of the UPC there is only one conclusion: it looks like a nightmare as it is very complicated.

One thing is nevertheless clear: if simultaneous translation is needed, the costs of simultaneous translation will have to be borne by the losing party! The UPC will only pay the costs for simultaneous interpretation needed by the panel. The proponents of the UP/UPC have remained very silent on this point.

The challenges

It is possible to follow Me Véron when he says: “whatever may be challenged in EU courts or constitutional courts will be challenged”.

I would however not be so confident as he is with the result.

The declaration of the “Depository” that the PPA has entered into force will be challenged first.

The non-adaptation of the UPCA to the consequences of Brexit is a second line of challenge.

I still have not heard any sound legal basis for the “provisional” allocation of the IPC classes meant to be dealt with in London to Paris and/or Munich. This also applies to the later allocation of those duties to another city.

The part-time technical judges will be challenged as well.

It would be interesting to know whether Me Véron endorses the solution which has been proposed: amend the UPCA under Art 87(2) at 8.00 on the day the UPC opens its doors at 9.00.

From the Oxford Dictionary:

fait accompli

/ˌfeɪt əˈkɒmpli,ˌfɛt əˈkɒmpli/

noun

a thing that has already happened or been decided before those affected hear about it, leaving them with no option but to accept it.

“the results were presented to shareholders as a fait accompli”

We still have the legal base for an EU patent court in the EU treaties. This mess of advanced cooperationhas to be resolved one day. And after the Batistelli reign the EPO also needs governance reforms.

I cannot but agree with you that the “advanced cooperation” is actually a mess.

I do not see a short term solution to the mess, unless the member states of the EU are forced to cooperate.

In view of the opposition the UP/UPC system by some EU member states, an enhanced cooperation was the only compromise possible in order to get it started.

There were too many vested interests at stake for letting the occasion go. Not only Poland will not ratify, but the Czech Republic will do the same.

With Brexit on top, and a UPCA without an exit clause, the mess is perfect.

I plead for abolishing the EPO and their arbitrary and incompetent patent screening and for letting competitors, third parties or the public challenge (published) patents in front of the UPC. We would get so a more certain and less expensive patent system …