As one of the most biodiverse countries in the world, Brazil has long been a natural research powerhouse. In fields such as pharmaceuticals, it is common to study the genome of plants, animals and microorganisms, applying this knowledge to create new products and processes that may be eligible for patent protection.

As an example, in September 2024, the Brazilian Patent and Trademark Office (BRPTO) granted a patent and issued a notice of allowance for another patent application, both filed by the Federal University of Ceará and covering compositions comprising natural products. One utilizes Brazilian biodiversity and is useful in treating Chagas disease, while the other uses African and Asian biodiversity and applies it in the treatment of prostate cancer.

Given its extensive biodiversity, it is no surprise that Brazil spearheaded the 20+ years of negotiations that culminated in the Treaty on Intellectual Property, Genetic Resources, and Traditional Knowledge. Approved in May 2024 by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), it made the headlines as the first WIPO treaty in over a decade.

The treaty establishes minimum standards for the contracting parties with respect to requiring patent applicants to disclose the country of origin and the indigenous or local community that provided the genetic resources on which the claimed invention is based.

For Brazil, this requirement is not new. The Brazilian Biodiversity Law (Law No. 13,123/2015) already regulated the Convention on Biological Diversity to allow sustainable use of biodiversity and sharing of benefits, while helping prevent biopiracy. To that end, Decree No. 8,772/2016 requires the use of national genetic resources to be registered with the Management Counsel for Genetic Heritage (CGEN), generating an access code. This access code must be informed when filing a patent application, together with a declaration that the invention has been obtained through access to Brazilian genetic resources or traditional knowledge.

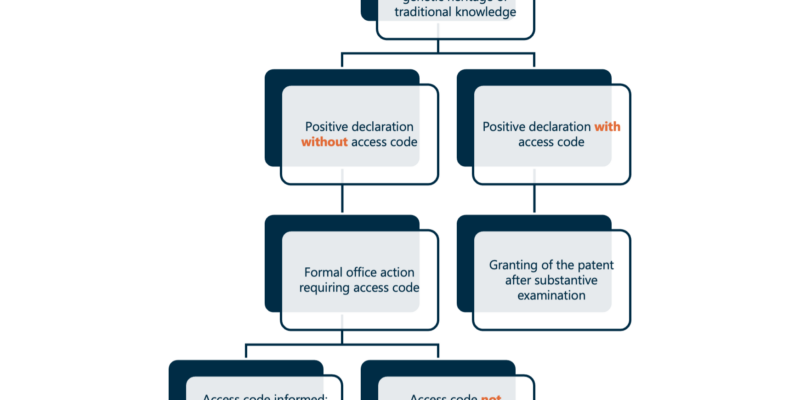

Failure to provide the access code will result in the BRPTO issuing an office action, requiring the applicant to comply, under penalty of having the application dismissed without examination. It is also crucial that the registration of access on SisGen occurs before the filing of any provisional application. Failure to have done so may result in a fine.

The chart below illustrates the procedure before the BRPTO:

While Brazil’s system for managing access to genetic resources is well-established, changes may be on the horizon with the implementation of the WIPO Treaty. The treaty assures applicants will have with the right to amend their applications before any sanctions are imposed, as long as “there has been no fraudulent conduct or intent.” It also stipulates that patent rights cannot be revoked or invalidated “solely on the basis of an applicant’s failure to disclose the information.”

In August 2024, the BRPTO published a notice on its Official Gazette that it would file lawsuits to invalidate patents granted without the required access code information. Patentees were given a 60-day term to either submit the missing access codes or correct their initial statement to reflect a negative access declaration. However, there remains uncertainty about whether the BRPTO can succeed in invalidating these patents under the terms of the treaty without relying on an unorthodox interpretation of the word “solely.”

On another note, while the implementation of the WIPO Treaty is expected to help increase transparency in the international patent system and have a significant impact on compliance with informed consent, there are still unresolved issues. For instance, it was agreed upon that amendments to the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) regulations might be needed to clarify if an applicant using the PCT must comply with these disclosures requirements when filing an international application, or if this will be required when entering the national phase before each contracting state’s patent office.

Another point of contention is whether the treaty imposes a disclosure obligation regarding digital sequence information, or whether this will be left to each contracting party to decide to implement as an additional obligation under national law. Such inconsistencies between national legal frameworks will undoubtedly pose challenges for patent applicants, as will the trigger for the disclosure. Brazil, for instance, used a broader trigger for disclosure than the one set out in the treaty, requiring disclosure when the patent is “based on” genetic resources and does not tie it to the invention necessarily “depend[ing] on the specific properties of the genetic resources”, as stipulated in the treaty.

While the approval of the WIPO Treaty marks a significant step forward in regulating access to genetic resources, much remains to be debated and clarified before it can be effectively implemented. In the coming months and years, we can expect disputes and further discussions, especially as countries like Brazil, with their existing frameworks, begin to reconcile their laws with the treaty’s new standards.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Patent Blog, please subscribe here.