In the spirit of Jonathan Swift’s unforgettable Modest Proposal for preventing the Children of Poor People from being a Burthen to Their Parents or Country and for making them beneficial to the Publick,

Let us first consider a Modest Proposal of how the European Patent Office could be restructured to achieve

• 100% EPO Quality (which substantially means timeliness and process efficiency),

• 100% Applicant Satisfaction,

• an enormously faster speed of the examination proceedings,

• diligent use of modern technology, perhaps even AI,

• fantastic and unheard-of cost savings, which might justify a significant extra premium for the EPO Upper Management; and last but not least

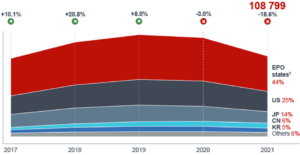

• higher satisfaction of the Delegates of the Administrative Council, who have recently displayed concerns about figures as shown in the following graph (decreasing number of granted patents per year), signifying less fees for the National Patent Offices.

Source: EPO

How to accomplish all of this with one simple change? Very easy:

Just stop search and examination, simply register all applications for grant and leave any disputes to the Opposition Divisions, Boards of Appeal and the Courts.

What a Brave New World this would be! The EPO finally at 100% efficiency. Much more money available for the EPO to be put into the stock exchange or into important exchange programs with National Patent Offices. Applicants 100% happy, because they finally get a patent for each of their applications and save costs for examination. EPO Upper Management almost certain to be highly rewarded for using the efficiency gains enabled by modern technology. The City of Munich will get back valuable and now superfluous office space. EPO Member States will earn fantastic validation fees every year. Delegates of the AC will no longer have to look at sad statistics such as the above. No more complaints to the Administrative Tribunal of the ILO. And no worries for the examiners, there will be plenty of well-paid jobs in private IP practice.

Okay, there may be a few companies here or there that could complain about just one minor aspect of quality of the new EP patents, i.e. substantive quality. But those companies are complaining anyhow, as Mr. President rightly noted recently:

“As a public service organisation we can expect negative feedback from time to time, as well as the positive. But for us to identify legitimate opportunities for improvement – and act upon them – we need feedback that is constructive and criticism that is grounded in fact and evidence”.

Therefore, nothing of importance seems to speak against my Modest Proposal and I just hope that I get a small percentage of the EPO savings once it has been implemented.

(Ok, just kidding…)

—

On a more serious note, you may perhaps wonder why there are nonetheless so many substantive examiners at the EPO and why I and many others are generally so supportive of them. Let me explain this.

The reason is the fundamental raison d’etre of the patent system, i.e. the idea that (human) inventors who have enriched the public with an invention that is novel, useful and inventive, should be rewarded with a temporary exclusive right, i.e. a patent. This helps to stimulate competition for the best ideas and to foster technological progress.

However, this concept requires an efficient filter mechanism that weeds out alleged inventions that are not novel, useful (industrially applicable) and inventive or that have not been described in a way that skilled persons can reproduce them.

Of course, you can leave everything to Opposition Divisions, Boards of Appeal and/or Courts, but you should also consider the less desirable consequences. First and foremost, you will need many more of these Divisions, Boards and Judges than you do now. Secondly, contentious proceedings before each of these bodies take a considerable amount of time and are expensive, particularly in Europe where you may have two instances before the EPO, followed by another two before national courts until the question of validity is finally settled. (Is there no room for some simplification and efficiency gains here? But this is for another post). Not every small or medium enterprise, let alone every single inventor, can afford such disputes. It is thus in the interest of a democratic society that awards equal rights to everyone (and every company) to provide, as a public service, an effective filter that separates the good from the bad inventions and provides for a reasonable certainty that the rights eventually awarded to patentees are good and valid.

The Court of Justice of the European Union recently held in C-44/21, paragraph 41 that:

In that context, it must be borne in mind that filed European patents enjoy a presumption of validity from the date of publication of their grant. Thus, as from that date, those patents enjoy the full scope of the protection guaranteed, inter alia, by Directive 2004/48 (see, by analogy, judgment of 30 January 2020, Generics (UK) and Others, C 307/18, EU:C:2020:52, paragraph 48).

Whatever one may otherwise think about this decision of the Court of Justice, this is the current standard, at least within the EU. Consequently, I think that the EPO should justify this presumption of validity by a reasonably rigorous examination of all patent applications on the merits before grant. You may now ask: But is the EPO not doing precisely this? Does the EPO in its current setup not provide such an “effective filter”?

The Industry Patent Quality Charter (IPQC) seems to think that it does not, at least that there is room for improvement, as it has been reported here and in other forums. I fully agree and may remind readers that similar concerns were expressed by about a dozen of renowned patent law firms in an open letter around 5 years ago. This letter led to one meeting with the EPO President as reported here in which the start of a “constructive dialogue” was envisaged by the EPO. I happen to be a member of one of the undersigning patent law firms. To the best of my knowledge, this “constructive dialogue” began and ended with this one meeting. Nothing further happened, at least no dialogue on this level.

If anything, it appears that the quality of EPO patents has further deteriorated since then. This can be concluded from one interesting set of figures that the IPQC presented to the EPO, i.e. the grant rate and the revocation rate following appeal over time, which is shown here:

Comparing 2015 to 2021, it seems that the EPO grant rate has increased from 61.5% to more than 70%. This looks great for patentees, but suggests that the filter function of EPO examination has slowly degraded. This conclusion is further corroborated by the amazing increase of the revocation rates following opposition appeal proceedings. As many as 46% of those patents that have been granted and opposed are now revoked by a Board of Appeal. In the “good old times”, the outcome of opposition and appeal proceedings was about a 1/3 mix in the first instance and 41% revocation on appeal.

These are the facts, and the EPO should not continue to ignore them and/or stonewall the messengers. Indeed, all the available facts and evidence clearly point to quality deficiencies in examination and, above all, searches. In the vast majority of cases, patents are later revoked because of state of the art that could and should have been found by the EPO but was not. The classic case is patent literature from same IPC class as the opposed patent, or even earlier patents by the same applicant. The EPO has or can easily procure detailed evidence to this effect by just analyzing Board of Appeal decisions and the prior art cited therein that resulted in the revocation of the patent.

Thus, search quality certainly can and should be improved. It should go without saying that examiners should not stop searching once they have found (or shown by the EPO IT support tools) one X document against claim 1 and a couple of A documents against all other claims. They should look into the subject-matter of all claims and thoroughly search for prior art of relevance thereto. They should be encouraged and enabled to also look at the examples and discouraged from providing an incomplete search by ignoring claim elements that they think are not patentable, e.g. because they are non-technical. Quite clearly, search examiners should be allocated sufficient time to perform a thorough search in each case. They should not be penalized for insufficient output if they need a couple of days or even a week or more for a complex application with 100 claims. Good quality needs time, and better quality needs more time!

The same is of course true for examination. Examiners should be encouraged to be thorough, not fast. Alas, the current trend seems to go into exactly the opposite direction. As one of the clearly knowledgeable commentators under the Kluwer Patent Blogger’s recent post on this subject rightly remarked (please read them in full!):

Maybe the IPQC would be interested to know that the pressure to reach more than 53K R71(3) communications before the end of May has gotten so high on line managers that they now routinely resort to instructing examiners not to spend more than a certain amount of hours on a search or examination action. Individual production is monitored on a bi-weekly basis at least. Time off work is discouraged. In the last weeks examiners are being put under immense pressure to grant everything they can and put non-grants on hold in order to “overachieve“ the COO’s instructions. Team Managers are clearly incentivised to reach these targets as their bonuses and grade and career advancements are made contingent on these being attained.

In the most complex technical fields that routinely took 2.6 days per product (that’s the internal language for a final action in search or examination) in the last few years, it has been decided by management that they cannot be more than twice as slow as the fastest technical fields that currently require 1.1 days per product on average. In 2023 no team is allowed to be slower than 2.2 days per product. How an increase of 20% in speed for large swathes of the office (mainly in CII!) can lead to an increase in quality baffles the mind.

Above average is the new normal.

Examiners are being pressured to ignore non-important aspects such as non-essential clarity (whatever that is) or minor Art 123(2) objections (the applicant is responsible for the text) in order to further speed up the process.

And the other one:

In the early days of the EPO, the search was comprehensive and the examination as well. There was no piecemeal approach. Examiners had time to do their work properly. Nowadays quality at the EPO resumes itself to timeliness.

The EPO indeed still seems to use a definition of quality that includes timeliness. I have criticized this for years and wrote a long post about the EPO’s quality problems on this blog in 2018. Unfortunately, these comments have not aged at all. They are at least as relevant as they were in 2018, and if I am allowed to make one serious proposal to the EPO, then it would be to take the recommendations by the IPQC and in my posts to heart and implement them.

The incentive system of examiners might also deserve a fresh consideration. Until about five years ago, examiners used to receive two points for a rejection of an application and one for a grant. This was then changed to one point for each of these decisions, yet a rejection causes about twice as much work. Guess what happened in the years following this change?

While I am not aware that issues like this are currently seriously discussed within the EPO, we instead observe an abundance of “quality lyrics”, i.e. a collection of propaganda, self-praise and hollow promises, which would deserve a post of its own. What the authors of such quality lyrics seem to be unaware of, though, is a fundamental law, namely the law of conservation of quality (Qualitätserhaltungssatz). In its shortest form, this law goes like this:

The sum of actual quality and propagandized quality is a constant.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Patent Blog, please subscribe here.

I would abolish the maintenance fees before grant and compensate them with higher designation fees proportional to the number of designated states.

I also would deduct (one or) two points of the examiner if a patent is (partially) revoked after opposition/appeal proceedings.

I am on the opinion that both your proposals appear not fully thought through.

Your first proposal would require an amendment of the EPC for various reasons:

– According to Art 79(1) all contracting states are designated in the application as filed.

– There is presently one designation fee for all contracting states and according to Art 79(2) + R 39(3), in principle, no designation is reimbursed.

– According to Art 79(3) a designation of a Contracting State can be withdrawn at any time up to grant.

Do not confuse designations with validations after grant.

I see thus little chance for your proposal to be considered.

The second proposal is as well not envisageable.

– For a start a decision in appeal on an opposition is taken years after grant. To be effective any sanction has to be as immediate as possible.

– A second problem is that in some technical areas there are no oppositions. Some technical areas are laden with oppositions. Oppositions can also vary in time in a given technical area. Oppositions can also vanish when proprietors sign non-aggression pacts.

– Overall only around 5% of the patents are opposed. Only focussing on the results of appeals in opposition would thus disadvantage certain examiners.

– Last but not least, an examiner gets his points in each calendar year and his production is an important part of the marking scheme. It is therefore not possible to retroactively reduce the number of points an examiner has acquired in the past. There would be no legal certainty for examiners. even the ILO-AT would not agree.

The problem lies with the upper management of the EPO.

Do not blame first those working in dreadfull conditions.

I think you might have overlooked some of the irony…

Knowing Patent Robot and his usual comments, I do not think irony has a place….

Actually, my first proposal was not ironic at all.

The second one was a little more provocative.

Maybe you are young enough not to remember that some years ago designation fees were proportional to the number of designated States. There is no need to amend Art. 79 for this purpose.

On the other hand, Art. 86 has to be amended to avoid renewal fees for pending applications. You could also obtain the same effect by reducing the renewal fees, which are really high, even higher than the renewal fees for granted unitary patents.

High renewal fees for pending applications are a deterrent for the EPO to grant patents quickly.

I can agree that in the early days of the EPO, the designation fees were only proportional to the number of designations. This was only valid up to 6 designations.

By paying 7 designation fees all contracting states were designated.

Under EPC 1973, the designation fees were originally due at filing, later before entering examination as they had an influence on the prior art under Art 54(3), cf. Art 54(4) EPC73.

In EPC 2000 the system was simplified and since, the ED do not have to check whether there are common designated states in case of prior art under Art 54(3). Art 54(4) EPC1973 was deleted.

If you want to levy a fee per designation, you will have to amend not only Art 79(1) but also Art 54.

Just compare the text of Art 79(1) EPC 2000 with Art 79(1) EPC1973.

As the contracting states are keen on getting their share of renewal fees, they want patents to be granted as quickly as possible. And the upper management has done and continues to do everything possible in this respect. You do not see many files ending as “submarines” in a cupboard.

Gosh, I forgot Art 54(4) EPC1973!

The renewal fees for pending EP applications are quite high. I do not understand why the AC allows their steady increase: the slower the EPO grants patents, the less the MS receive after grant.

High renewal fees are a deterrent….

Weird, our management is pushing us to grant as fast as possible, which seems to counteract your reasoning completely.

Why would our management do that?

Furthermore, I as examiner are not concerned with how old my files are, beyond the fact that I am penalised for being in a field that has always been understaffed, and thus has never been able to treat examinations with any priority (my grants are “too old”, and that reflects my “timeliness”, which is measured by the average age of files I grant – not average age of files in stock).

My pay simply does not depend on whether my files get old or not.

Thorsten, I fully agree.

It would be nice if the EPO were to sit up and take notice of your proposals. Given that serious complaints about quality are now coming from users whose fee payments fund the EPO, it is hard to imagine that the EPO’s management can continue to (completely) ignore those complaints.

Nevertheless, I do think that the EPO’s management will be far more inclined to adopt your first proposal than your second. Whilst you and I may be horrified by the thought of the EPO turning into a rubber-stamping authority, this is (and has been for about a decade) the undeniable direction of travel. Increases in the EPO’s “profitability” provide financial rewards for the EPO’s management and (the offices of) the AC delegations / delegates. Therefore, asking them to prioritise actual quality over such financial rewards is like asking turkeys to vote for Christmas.

When the EPC was first drafted, I imagine that its authors envisaged the national patent offices as being competitors to the EPO … and hence that a supervisory body run by delegations from the national offices would provide suitable governance / oversight. Whether or not this view was justified at the time, it is probably the biggest mistake made by the EPO’s founding fathers. Indeed, things have got so bad now that when one looks at the dictionary definition of “regulatory capture”, it just reads “See the Administrative Council of the EPO”.

Thus, for your more serious proposal to stand any chance of gaining traction, my view is that it really needs to be coupled with an overhaul of the EPO’s governance … as otherwise, whilst the turkeys may throw users a few scraps, there is zero chance of them ever voting for Christmas!

As long as the tail will be wagging the dog, there is no chance that things will improve at the EPO.

The founders of the EPO never envisaged that the „cooperation“ budget would actually be misused as bribery system to buy votes.

All presidents of the EPO played with the cooperation budget, but none, besides the Napoleon of the 10th floor and his successor, developed it to such a corruption instrument. After each AC session the cooperation budget is tailored to the voting behaviour of the delegations at the AC. Like in the EU, the principle of one country one vote has led to such problems!

When the boards were exiled to Haar, the vote was acquired thanks to the smaller countries which file very few applications, but have full vote!

The same delegations are now voting, without any shame for bringing the boards back into town!

It is not only the the EPO’s governance which needs to change, but also the AC to revise its position in order to play again their role of controlling the EPO!

You have every right to express criticism on the management of the EPO and the delegations of the AC, but assertions of corruption and bribery are clearly beyond the pale.

Mr Hagel,

You have every right to have your own opinion, but I doubt you have evidence that the cooperation budget is used as you imagine. First, should there even be a cooperation budget, which after all is financed by the fees applicants have to pay. Then if there should be a cooperation budget, should it be as large as it is. The cooperation budget is approved by the Member States for their own benefit. Doesn’t that say enough?

Are you aware of what the money really is used for, whether it is used for projects that benefit the EP applicants? What has been reported in previous comments could have been proven incorrect if this budget was transparent. It has been a while now that delegations do not dare vote against the EPO proposals for fear of reductions in a share of the cooperation budget that they (unfortunately) need. Lately, the German delegation must have felt lonely …

Thus, in my opinion, the words that you criticise alas reflect a situation that I sincerely hope will change.

I can only support what has been said by A. Nonymous.

It is the sad reality.

Now you know why the AC is not controlling the EPO, but the upper management is controlling the AC.

A lot of money from the users is being wasted in order for the AC to abide by the wishes of the upper management.

This cannot be criticized enough!

Thanks to T. Bausch who managed again to combine an amusing story with very serious proposals.

It should become more and more difficult for the upper management of the EPO to deny quality problems. especially at search level. But denial and verbose statements without content are nothing new in the Isar building and especially on the 10th floor.

If people are pushed to grant, they will do as required since they do not want to get fired for incompetence.

I am of the opinion that incompetence is not with examiners but with those taking decisions without having any clue of the work done.

This is going on a par with a big disdain for examiners and their work. As a famous tenant of the 10th floor once said “duds go into the patents”, not realising that he was himself belonging to this group. He has then started to harass its staff. And its successor continues. We see the result today.

The problem is that those people and the delegations in the AC do not realise that they are actually sawing the branch on which they are sitting. You can milk a cow for a long time, but it comes a moment when the cow will dry up.

It is a pity to see an organisation like the EPO run into the wall by would-be managers.

EP grant numbers for 2022 are down to 81.762, another 24.8% decrease. Although I am only a humble service provider and not a patent attorney I understand the quality over quantity argument. However, the current situation of ever more filings (just under 5% per annum) and vastly reduced number of closed files, will not improve the quality of patents. A growing backlog puts more pressure on the patent office and the examiners. Unless the pressure is reduced patent quality will continue to deteriorate. How long until the first patent is granted just in time to pay the 20th annuity?

The figures about revocation rate can be explained in a slightly different manner.

Basically, what we are discussing here is inventive step. Novelty is simple enough and clarity is not a ground for opposition.

Obviously inventive step depends on the prior art found. If the search is bad, everything is novel and inventive. I certainly agree that search should be as good as possible. But, generally speaking, search is not that bad. Other patent offices rarely find much better documents (and when they do, we usually check them and introduce them in the procedure). There is room for improvement, but not necessarily a lot.

The examination side may be more of a problem. If the criteria in the examination procedure is lower than the one in the opposition procedure, you will have more revocations. My feelings are that some of this is at play. I don’t know whether my feelings are true, I only see a small part of the Office as a whole, but the latest instructions on inventive step appear to make it very difficult to draft a rejection, unless everything is in the prior art, including how to combine the documents. That is very close to novelty.

The problem is that it is more difficult to find proper documents for IS in an electronic search.

For novelty

“But when the opponent comes with a highly relevant novelty destroying novelty, or even prior art under Art 54(3), do not tell me the search was OK!

Whilst I can follow your considerations about the quality of the application , this point might be turned around. What was first there, the bad search or the bad applications. In other words, what was first, the chicken or the egg?

There is room for improvement: search correctly!:

15 – 20 years ago, the idea was raising the bar for IS.

Now it seems more lowering the bar, so that there are more grants. ?

I cannot that that it is more difficult to find documents for inventive step in an electronic search, but I suppose it may be different in different technical fields.

And again: I don’t think the quality of the search is generally bad. That, again, may depend on the technical field, some are very difficult to search (and they were also difficult to search on paper, I think). But in the few fields I know, I can compare the searches in the EPO with searches in other offices and I don’t feel that they are vastly different. Of course, patent offices check the searches of the others, so I can only compare the earliest search of one file to the earliest search of another file.

You are bringing forward that the quality of search is still better than that of other offices. This is exactly what is claimed by the upper management of EPO.

The problem is however that it happens that when the patent is revoked or maintained in amended form. It is only in very few cases due to prior art which could not be available in the search documentation, like public prior uses, catalogues etc.

When the opponent brings the highly relevant document when the search Report is laden with X or A documents, it is difficult to consider that the search was of good quality. The same applies when the opponent turns out with Art 54(3) prior art, sometimes from the patent proprietor.

This is the problem which has been put to light!

Examiners are not to be blamed as such. It is the whole system set up by the management of the EPO which is the cause.

If the measures mentioned in the quality charter would be actually applied, the EPO would not be under criticism.

Quality is more than timeliness,

It is delivering searches which gives a high presumption of validity.

When barely 15% of patents do come out untouched after opposition it becomes alarming. In the past, this proportion was around 1/3. Those days have gone

Another, separate comment. You mentioned artificial intelligence. It goes without saying that the management of the EPO is interested in artificial intelligence, if is very fashionable at the moment.

There are two problems:

1: very few people are able to design AI systems and private companies can offer them considerably more than what the EPO is prepared to pay.

2: AI is very sensitive to adversarial poisoning. That means that any AI system can be “poisoned” by somebody deliberately feeding it specially crafted data. That will be a problem for patents.

Thorsten, you are very persuasive but I’m not (yet) totally convinced how vital it is for the EPO, before it grants somebody a patent, to work with a fine-toothed comb through each and every provision which the EPC makes about patentability. As everybody agrees, the EPO is a “public service” organisation and what service the public needs from a patent system is that good inventions receive protection that is speedily enforceable against infringers and that bad inventions are weeded out and quckly shown to be unworthy of exclusive rights. Who provides that public service is debatable. With 10 year petty patents, or copyright, for example, it is more the courts than the Patent Office. Prior to 1978, the UK Patent Office looked at novelty but not at obviousness (because back then it was thought that only in inter Partes proceedings can the obviousness enquiry be conducted effectively). It was the courts, not the Office, that did the weeding out. It is not absurd to argue that the Patent Office (like the pre-1978 UK Patent Office) should deliver a first class search report but then, after that, the Applicant (as opposed to an EPO Examiner, or Examining Division) should take care to go to grant with documents that will withstand a determined and well-financed post-issue assault on validity and courts will decline to help those patentees who were negligent in their conduct prior to grant. Caveat emptor is a very good principle. Rely on the self-interest of Applicants to do their own scheme of prosecution amendment, after they have been given a first class search report to work with.

Times change. I am not convinced that all those corporations demanding better examination performance from the EPO are willing to pay for it. They want the EPO to refuse all the applications from their competitors while allowing all of the applications they themselves file. The AC members so busy slicing up the EPO profits cake will say that public service is pre-eminent, in that they are taxing the big corporations and spending EPO dividends on public services, that the best way to deliver ever greater “public service” from the EPO is to adopt your “modest proposal” in full. Milk the cash cow ever more efficiently for the good of the public. Grant entry tickets to the courts, and let the courts grant patent owners all the financial relief from infringement that they crave. Then there will be no further fall-off in the number of patent applications filed, even when the EPO fees are exorbitant.

Management performs to “make the numbers”. Counting how many patents are granted per quarter year is an easy number to count. Counting how many hours it takes (on average) to perform an FTO analysis for Europe is hard enough already. Suppose the EPO grants willy-nilly, without any examination of patentability. How many more hours will an FTO analysis then take? 10% more? 500% more%. Who knows? And anyway, who cares?

Given the commoditization of patent attorney services, I too am not convinced that these corporations actually want to pay for the services that they demand from the EPO. Words are cheap.

@Max Drei,

What you suggest is another way to look at the usefulness of patents.

Just carry out a search and leave the courts to decide is what has been done in France after 1968. And yet France has now started examination and opposition procedures. There must be a good reason for it.

If you go further, it is best to let peer review decide.

But why should we then need qualified representatives as well as substantiveexaminer

The problem is that the search quality at the EPO is going down!

Why is it that there are more revocations than maintenance in amended form. ‘

The number of rejections of oppositions is modest in comparison.

France does not examine novelty or inventive step. Check the instructions for the examiners published at the INPI web site.

If they did, they would need vastly more examiners than what they presently have.

I do no know which version of the instructions to examiners you have consulted.

Just look at page 97 and following of the document with the following link:

https://www.inpi.fr/sites/default/files/DIRECTIVES_BREVETS_LIVRE1_INSTRUCTION%20DES%20DEMANDES_140422.pdf

I quote directly page 103 Activité Inventive 5.5. Examen par l’Institut

Pour les demandes de brevet ayant une date de dépôt antérieure au 22

mai 2020, le Code n’a pas prévu le rejet d’une demande de brevet pour défaut d’activité inventive.

L’examinateur ne pourra pas notifier de rejet sur la base de ce motif.

Néanmoins, l’activité inventive est prise en compte par l’Institut pour établir le rapport de recherche préliminaire et l’opinion l’accompagnant, le rapport de recherche accompagnant le brevet délivré (cf. titre I, section C, chapitre VIII) et l’avis documentaire (cf. titre II, section C).

Pour les demandes de brevet déposées à partir du 22 mai 2020, le Code a prévu le rejet des demandes pour lesquelles l’invention n’implique pas d’activité inventive en considérant que son objet n’est pas brevetable selon le premier paragraphe de l’article L.611-10 (cf. titre I, section E).

Le rejet pour défaut d’activité inventive peut s’appliquer à une ou plusieurs revendications d’une demande

Even if French is not your mother tongue, as EPO examiner you should be able to understand that inventive step plays a role in the examination by the INPI.

Very off-topic here, but this is indeed a quite recent change that has come with the “loi PACTE” from 2019. The INPI has been recruiting examiners to cope with it.

Indeed the INPI instructions changed in 2020, I had not realized that. The text you cited explicitly said an application could not be rejected for lack of inventive step before that date: “L’examinateur ne pourra pas notifier de rejet sur la base de ce motif.”

Still the conditions for rejection at page 122-123 are similar to what the practice was before that date: the applicants are asked to comment and/or change the claims on the basis of the search report. If they do that, it is a patent. In my opinion, this is still not an examination system.

An important aspect not mentioned above is quality at source. Whatever about the effectiveness of the quality filter function of the EPO it is very difficult to make a silk purse out of a sow‘s ear. The drafting quality and size of the incoming applications very often leaves a lot to be desired.

The quality of search is clearly dependent on the intellectual investment of the examiner in analyzing the application and defining a proper search strategy. The next hurdle is the sheer volume of information sources and databases which have to be consulted. The amount of possible prior art sources has increased dramatically over the last 10-15 years with the surging availability of information in the digital transformation. There is no such thing as a perfect search nor is the requisite time envisaged. The search fees on average don’t even cover the costs of the initial search and opinion.

What you are saying here is the mere repetition of what every search generation says: life was easier for the preceding generation.

When searching electronically, you can compare it with a fisher on the side of a lake.

He will have a hit for a novelty destroying document much easier than for inventive step.

The search as such can be quick. What is needed is more intellectual investment!

Searching is more than using a few “preparations”!

The procedural fees do not cover the costs. The renewal fee do the trick.

Ever compared the fee for appeal with the actual costs a dealing with an appeal?

Aliens in the patent world.

“The search fees on average don’t even cover the costs of the initial search and opinion.”

Of course, they don’t. The cost of a search is somewhere above 3000€, and that is what patent offices have to pay. Applicants pay less, but they pay maintenance fees. QED.

Happily someone mentioned quality at source. EPO examiners alone cannot create quality patents from poor-quality applications. Does this make sense? Thorsten was talking about patents with 100 claims. Come on! No invention deserves 100 patent claims, but we see such applications everyday. Remember claims conciseness and indication of essential features, art.84, rule 43? Do applicants have access to the prior art relevant for their inventions themselves when drafting? Do they only rely on the EPO search? Remember rule 43? Similarly with art.83…. Some quality pre-requisites must come with the application ex tunc. No quality search can be reasonably performed where this is lacking, and examination then becomes extremely inefficient. For quality patents must necessarily result from a fair and loyal applicant-examiner cooperation. Should we devote some thoughts to the fatal combination of huge numbers of low quality applications and EPO management serving only greed-driven big corporations? Would that help complete the picture?

The second “rule 43” was obviously rule 42, which I quote: 1) The description shall: (b) indicate the background art which, as far as is known to the applicant, can be regarded as useful to understand the invention, draw up the European search report and examine the European patent application, and, preferably, cite the documents reflecting such art;

(c) disclose the invention, as claimed, in such terms that the technical problem, even if not expressly stated as such, and its solution can be understood, and state any advantageous effects of the invention with reference to the background art.

This is not wishful thinking; this is the EPC: this is what applicants must provide with their applications upon filing if they want a quality search and examination; this is their part in the deal.

If the quality of incoming applications was as bad as you claim, then a search would not be possible and lots of communications under R 63 should be issued.

The quality of the incoming applications has very little to do with the quality of the search.

If the claims are understandable from a technical point of view, a search is possible and should deliver the best basis for a thorough examination, and not to patents which come out maimed from opposition in 85% of the cases, on the basis of documents which were in the search files for more than 90% of the cases

A quality patent application fully disclosing novel and inventive subject-matter would result in a 100% quality patent even without search and examination filters. The real problem is the tons of crap patent applications distorting the patent system in the interest of a few and patent office policies serving these interests.

I might agree with you that there are “tons of crap patent applications distorting the patent system in the interest of few”, but have you asked yourself why?

That the EPO grants any crap does certainly play a role. The number of refusals is rather law, but the number of patents coming out maimed from opposition shows that in all those cases that the patent should never have been granted in the form it was granted.

If all applications were “fully disclosing novel and inventive subject-matter” would render examiners redondant. Have you ever thought of this?

Where is the problem? Crap patent applications must be refused. Full stop.

A few thoughts on this:

1. I can empathise with some of the criticisms raised by the IPQC. Clearly it can help applicants (and examiners, and 3rd parties) to get a thorough search. Similarly, deeming certain claim features unclear or non-technical before the search and then not searching them is unhelpful for the applicant (and others). The claimed subject-matter should be searched, any objections can still be raised in the search opinion.

2. Another example of poor quality is poorly reasoned objections (e.g. just reciting the claim language with a few reference signs from D1 usually isn`t very helpful or convincing). Providing scarce analysis / objection on 54, 56, while trying to get the applicant to narrow a claim based on far-fetched clarity/essential features objections is another irritation. Sometimes feels as if examiners see that as a quicker/easier way to get a more limited claim and an allowance. Not really fair to either the applicant or 3rd parties. And don’t get me started on examiner amendments to the claims at 71(3) stage with no indication of basis..

3. All that said, the EPO still provides a high quality, in my experience better than other national offices in Europe and better than other major patent offices.

4. Re the statistic on grants cited in the article: From other statistics I’ve seen, the grant rate has gone up over recent years but so has the refusal rate. So the ratio grant/refusal hasn’t shifted that much. Deemed withdrawals are down. Perhaps because examination is quicker, fewer applicants lose interest before a final decision?

5. Re the statistics on revocations cited in the article: The decrease in revocations at 1st instance is interesting. My subjective view is that OD’s have become more patentee friendly in recent years, but that is hardly based on a statistical sample size. As for the Boards, is the higher rate of revocation driven in part by the tougher procedural rules? In any event, the difference in % revocations between 1st instance and appeal is interesting. Perhaps part of the difference can be explained by appellant behaviour, i.e. which party (patentee or opponent) is more likely to appeal a 1st instance decision? Finally, from other statistics I’ve seen, the final outcomes of opposition proceedings (i.e. final decision, whether that was reached at 1st instance if no appeal, or if reached after appeal) haven’t moved so much over recent years, i.e. ratios of patents maintained as granted, amended, revoked.

6. Admittedly this is nitpicking a bit, but the sentence “As many as 46% of those patents that have been granted and opposed are now revoked by a Board of Appeal” isn’t quite right. This is 46% of the patents that have been opposed and that have gone to appeal. That is a skewed sample of all of the patents that have been opposed. See my comment above about which party is more likely to appeal – I’d have to check, but I think opponents appeal more often than patentees, e.g. where a patent is maintained in amended form.

7. In my view, whether timeliness is considered part of ‘quality’ or not, it is nevertheless still important. If you think back ~ 15 years the EPO was slow and many applicants didn’t like that, especially paying renewal fees while nothing happened. A patent office should deliver reasonable decisions (not perfect ones) in a reasonable timeframe. By comparison, I routinely see communications from the German PTO stating that “in view of the number of earlier filed applications and the workload of the examiners no date can be given for when this application will be examined. In recent years the number of examination and search procedures has increased considerably and with it the workloads of the examiners. Therefore, longer waiting times unfortunately cannot be avoided at the present time”. That’s not good service to the applicant or to the public. It prolongs legal uncertainty for applicants and 3rd parties. Imagine the criticism the EPO would get if it routinely sent out communications like that…

8. Following on from 7, as I’ve raised before on here, it does seem ‘easier’ to criticise the EPO than national institutions. Maybe it is a psychological thing, it being more ‘difficult’ to criticise your own country’s institution, at least on a forum with foreign readers. e.g. there was an article in praise of the outgoing DPMA head on here recently, while that same patent office sends out communications as mentioned above. And can we Germans criticise the quality at the EPO and the need for a quality examination (see the article “Of course, you can leave everything to Opposition Divisions, Boards of Appeal and/or Courts, but you should also consider the less desirable consequences……contentious proceedings before each of these bodies take a considerable amount of time and are expensive,….. It is thus in the interest of a democratic society that awards equal rights to everyone (and every company) to provide, as a public service, an effective filter that separates the good from the bad inventions and provides for a reasonable certainty that the rights eventually awarded to patentees are good and valid”) while simultaneously maintaining our utility model system?

A modest proposal would be to respect the Law (EPC art52) and restore freedom of programming computers.

Another more radical proposal would be to transform the EPO into an EU agency, without any ‘self-financed’ objective to pressure examiners to grant as many patents as possible.

You must be a friend of Zoobab.

The case law of the EBA and BA has made clear how to deal with CII.

Not allowing patentabilty just because you need a program would be denying lots of inventions the possibility of being patented. Is this what you want? For instance, lots of control functions are nowadays using CII. Denying protection for those technical items would be ludicrous.

What is not patentable is a program AS SUCH! As soon as a program has a link with a technical reality, it is patentable. And rightly so.

Transforming the EPO as an EU agency is not possible as there are 39 contracting states at the EPO and only 27 at the EU.

“Good quality needs time, and better quality needs more time”.

It is now on my office door.

Thanks for your efforts Thorsten.

I’ll come to you when I am fired from the EPO.

Good quality does not necessarily need more time,

It needs a good training to start with.

Well trained examiners will know what to do.

This is not any longer the case.

Experienced examiners are leaving the office as soon as soon as they can.

A big source of knowledge is thereby lost.

Examiners cannot be blamed when they play with the system as well as the system plays with them.

I feel deeply sorry for examiners. They are “managed” by a bunch of incompetent people who do not have a clue about the work done and are hypnotised by Excel tables!

The biggest problem at the EPO is that those who carry out the work have the same qualifications as people sitting in management. The management has never understood this. The present management even less than their ancient predecessors

Why does the upper management push for patents to be granted as quickly as possible?

Mr bausch complained on this same blog about this frantic move to quick grants!

When patents are granted as soon as possible, it means that renewal fees go much earlier to national patent offices/national budgets, as they can keep 50% of the renewal fees.

This combined with a very specific use of the “cooperation budget” explains why the AC has given up its control function and the tail is wagging the dog.

All presidents of the EPO have at times played with the “cooperation budget”, but the present incumbent and its predecessor have institutionalised the process to their clear advantage.

The AC is rubber stamping anything coming from the 10th floor. Whether it corresponds to the letter and spirit of the EPC has become irrelevant. The chair of the BA also plays a role when looking at decisions like G 3/19 and G 1/21.

The president of the EPO and its predecessor are primarily to blame for the degradation of quality, but the AC is contributing too!

In the past it happened that the AC sometimes first refused the financial discharge to a president and even nipped in the bud a president’s desire to build a new building for the EPO, cf. EPO 2000 in Voorburg.

This also explains why in The Hague it took so long to built a replacement for the tower built at the time by the IIB.

In those days the AC played the role it was meant too!

When the EPO was set up, existing international organizations were more controlled by the AC than by the heads of the organization.

At the EPO, the head should get more power.

This worked fine as long as the heads of the office were reasonable. Since roughly 2010 this is not any longer the case.

The presidents just think that immunity means impunity. They act accordingly. They think the office is their private playground.

The AC, is for obvious reasons, see above, not any longer controlling the office.

Hence the present problems of bad staff relations combined with dwindling quality.