When a company is not prepared to charge a socially acceptable price in the Netherlands for a medicine, the government should use other instruments such as compulsory licences, encouraging pharmacy preparation and allowing patients to order medicinal products abroad in order to ensure that the medicine is available for patients. The Dutch Council for Public Health and Society (RVS) recommends this in an advice to the minister of Health, Welfare and Sport (VWS), which was published earlier this month.

The advice, ‘Development of new medicines. Better, faster, cheaper’, had been requested last year by the former minister of WVS, Edith Schippers, who questioned the efficiency of the development of new drugs and wanted suggestions for alternative approaches. Schippers was concerned about the exorbitantly high prices of some new medicines; figures of over €100,000 per patient per year not being an exception.

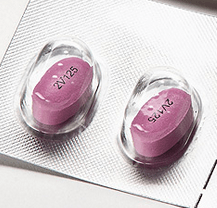

Last month for instance, the high price of the drug Orkambi for treating cystic fibrosis came under fire in the Netherlands. The drug was not authorised for the mandatory health insurance package ‘because the manufacturer was demanding an excessive price and the pricing negotiations had failed’. In the end, after months of negotiations and the publicity, an agreement was reached.

Last month for instance, the high price of the drug Orkambi for treating cystic fibrosis came under fire in the Netherlands. The drug was not authorised for the mandatory health insurance package ‘because the manufacturer was demanding an excessive price and the pricing negotiations had failed’. In the end, after months of negotiations and the publicity, an agreement was reached.

According to the RVS report, ‘more and more often medicines are being developed for small groups of patients. These medicines can mean a great deal to those patients but are often (extremely) expensive at the same time. There is no longer a relationship with the R&D costs, or even with the added value. This is endangering the affordability of care.’ In its advisory document, the RVS extensively discusses the ‘extremely inefficient’ development process of medicines and the problem of pricing in a monopolistic market. It points out:

‘For rare conditions, this monopoly on medicines is strongly exacerbated by the European regulations that came into force in 2000 for orphan drugs. These are medications for conditions that occur in the European Union in less than five out of every 10,000 inhabitants. In addition to protection by patents, a company has additional protection such as ten years’ market exclusivity after licensing. This means that no medicines based on the same mechanism of operation for the disease in question may be put on the market during that period. The regulation has strongly encouraged the development of new orphan drugs. It has however also had the perverse effect of medicines being investigated and licensed for narrow and restricted indications in order to obtain the status of an orphan drug, while the study results indicate that its efficacy is broader.’

Reining in the high prices

The RVS outlines several ‘solution directions’ for ‘reining in the high and very high prices’. Basically, European patent system must be revised, according to the Council.

‘Many experts believe, particularly in the case of medicines, that the method used for encouraging innovation (the patents system) creates more trouble than it resolves. They make the case, based on the interests of public health, for excluding medicines from patenting. This was incidentally the case until recently in various countries, such as Brazil and India. This only came to an end when the international TRIPS Agreement (Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights) came into effect on 1 January 1995. That treaty originated in initiatives in the early 1980s by Edmund Pratt, CEO of the American pharmaceuticals company Pfizer, and John Opel, CEO of the computer company IBM.

The TRIPS Agreement and national patent legislation give countries options for tackling misuse of patents, for instance through compulsory licences. Countries are however extremely reluctant to use such measures because of the fear of trade repercussions (…).’

However, the RVS ‘believes that it is not feasible given the current international power relationships – certainly not in the short or medium term – to exclude medicines from patenting worldwide and to develop new medicines using only public resources and get them on the market. It is important though that the problems with the current patents systems should be put on the international agenda.’

In the short term, several other tools are available for the authorities in order to comply with their task of keeping healthcare affordable and promote public health, the RVS argues. It presents four options:

‘1 Compulsory licences

Article 8 of the TRIP Agreement expressly allows measures that protect public health and Article 31 creates the possibility of issuing compulsory licences. The Dutch Patents Act also offers such an opportunity. Granting compulsory licences means that other companies are allowed to make the patented medicines and put it on the market in the Netherlands. This creates competition, which will make prices drop. When compulsory licences are issued, there is a requirement though that the authorities must observe the boundaries set by the Paris Convention and the TRIPS Agreement in particular, which give fairly detailed limits for issuing compulsory licences. (…)’

The RVS points out that ‘countries are often reluctant to issue compulsory licences, partly out of fear of economic reprisals and partly out of ignorance’, and it gives some examples of what happened in this respect in the past. The majority of compulsory licences for medicines were issued in the period 2001-2006 by countries such as Brazil and South Africa for medicines against HIV/aids, but it happened in Italy and France as well.

‘2 Encouraging pharmacy preparation

If a pharmacist prepares a medicine on prescription for immediate use by an individual patient (known as extemporaneous or pharmacy preparation), any patent on the medicine does not apply. (…) The knowledge required for preparing medicines in the pharmacy is available in abundance in the Netherlands.’

Regarding the recent Orkambi-debate, the RVS points out: ‘The two active ingredients, ivacaftor and lumacaftor, are both easy to order via the Internet from China. (…) It is not inconceivable that a generic variant of the drug will be available within the foreseeable future on the Indian market. A Dutch pharmacy would be allowed to import the drug for its own patients. Although pharmacists have this right in law, they do not dare to exercise it out of fear of legal reprisals by manufacturers. This did actually happen in the past to a pharmacist from The Hague. (…) If the authorities genuinely want to be able to use this tool in practice, they will have to protect pharmacists against such tactics.’

‘3 Allowing patients, on a doctor’s prescription, to purchase medicinal products abroad for their own us (for example via the Internet) and have them delivered in the Netherlands (…)

4 Tackling abuse of positions of power

(…) Article 102 of the European Union’s own Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union forbids misuse of a dominant position. Based on the Dutch Competitive Trading Act, the Netherlands Authority for Consumers and Markets (ACM) can take action against abuses of positions of economic power. If a company is guilty of this, the ACM can impose fines that can be as high as 10% of the company’s net annual turnover.’

Other approaches

In order to make medicines more broadly available to patients, other solutions are possible as well. The RVS suggests the Dutch authorities could allow patients to purchase medicines for their own personal use via the internet. ’Facilities should be made available at which the patients can have the quality of their medicines tested anonymously, just as is currently done with hard drugs.’

Apart from this, new ways of negotiating with pharmaceutical companies could be explored: ‘For medicines that have a major budgetary impact, the authorities can select a single drug from the various alternatives through a tendering process. (…) Another possibility is that the authorities can enter negotiations with the manufacturer to buy off the development costs of a new medicine for the Netherlands, based on the scale of the Dutch market (1% to 2% of the global market).’

Bundling expertise will help as well, says the RVS: ‘it is important that inventions made by public research institutions [in the Netherlands, ed.] are appropriately patented. At the moment, the requisite knowledge is fragmented, scattered among a number of Technology Transfer Offices (TTOs). The Council therefore recommends bundling the expertise into a national TTO for new medicinal products.’

At the presentation of the RVS report, Dutch minister for Medical Care, Bruno Bruins, the successor of Edith Schippers in the new Dutch government said: ‘The conflict about expensive medicines is not a conflict between the authorities and patients, but between the pharmaceutical companies and the interests of the society.’ He will react to the content of the advice in the upcoming period.

For regular updates, subscribe to this blog and the free Kluwer IP Law Newsletter.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Patent Blog, please subscribe here.