Introduction: A Concert Interrupted

Imagine a Rammstein concert—tight rhythms, explosive precision, and overwhelming power. That’s what many expected from the German divisions of the UPC: efficiency, control, and dominance. But two years into the life of the Court of Appeal, that expectation has begun to unravel. What we see instead is a more nuanced performance—less industrial metal, more unexpected dissonance. The Court of Appeal is not playing along with traditional tempo. It’s rewriting the setlist.

In economic terms, this resembles Joseph Schumpeter’s concept of “creative destruction,” where no established order can endure indefinitely at its peak; new entrants and shifting dynamics inevitably disrupt the status quo. Philosophically, it echoes Heraclitus’s notion that “everything flows”—no position of dominance remains static (Heraclitus was the favorite philosopher of the “the little magician from Messkirch”, if you catch the drift).

I. Statistical Composition: The Raw Numbers

Over the last twenty-four months, the UPC’s Court of Appeal has issued rulings in 41 cases spanning electronics, pharmaceuticals, biotechnology, mechanics, and related fields. Litigants treat the Court of Appeal as a reactive instrument, bringing urgent first-instance injunctions or infringement judgments before Luxembourg’s bench for reappraisal. The breakdown by type of first-instance action is as follows:

-

Infringement actions: 49 percent of all appeals.

-

Provisional measures/preliminary injunctions: 36 percent.

-

Revocation (nullity) actions: 13 percent.

-

Declarations of non-infringement: 2 percent.

This distribution shows that parties seize first-instance relief quickly, then entrust Luxembourg to confirm or correct those decisions. Not every high-speed, high-stakes choreography survives the “second act.”

II. The Appeal Effect: When the Beat Drops

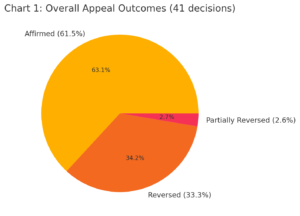

Once the Court of Appeal has weighed in, roughly 36 percent of first-instance rulings do not survive intact. Specifically:

-

61.5 percent are affirmed.

-

33.3 percent are fully reversed.

-

2.6 percent are partially reversed.

In economic terms, this calls to mind Kondratiev’s long-wave cycles: rapid upward surges often contain the seeds of downward correction.

When the Court of Appeal confirms a decision, it confirms both the legal reasoning and factual findings of the local division. When it reverses, it signals that the first-instance judge’s interpretation of law or weighing of evidence was incomplete. Even partial reversals—though numerically small—highlight how Luxembourg can fine-tune single legal or factual issues without discarding the entire outcome.

III. German Divisions: Preeminence and Exposure

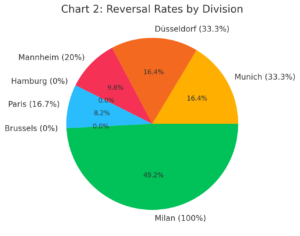

From the UPC’s introduction, Germany’s local divisions—Munich and Düsseldorf—drew a majority of filings. Their quick dockets and recognized expertise made them “go-to” venues. Yet high volume brings high exposure. Over these 41 appeals:

-

Munich faced a 33.3 percent reversal rate.

-

Düsseldorf likewise recorded 33.3 percent.

-

Mannheim showed a 20 percent reversal rate (on a smaller sample).

-

Hamburg, handling few cases, still has 0 percent reversals (though its sample remains limited).

When all German divisions are aggregated, the average reversal rate is roughly 30.4 percent. By comparison, Paris stands at 16.7 percent, Brussels at 0 percent (from very few matters), and Milan’s single appeal so far was fully reversed (100 percent)—a reminder that one data point cannot establish a lasting trend.

At first glance, these figures might appear unfavorable for the German divisions. In reality, volume explains most of it: Munich and Düsseldorf handle far more cases than any other UPC forum. A greater caseload naturally leads to more appeals and, consequently, a higher count of reversals. Still, the crucial takeaway is that no single division—German or otherwise—enjoys exemption from appellate correction.

IV. Provisional Measures: The Risk of Overdrive

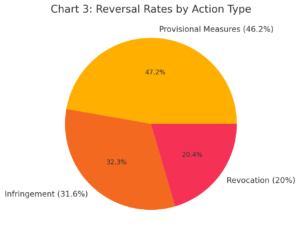

- Of all first-instance actions, provisional measures (we included preliminary injunctions and one measure to preserve evidence) have the highest appellate reversal rate: 46.2 percent.

-

Infringement actions: 31.6 percent reversal rate.

-

Revocation (nullity) actions: 20 percent reversal rate.

When a first-instance judge grants an urgent interim remedy under compressed timelines—often without full expert testimony or cross-examination—the Court of Appeal has every incentive and capacity to revisit underlying assumptions, evidence, and legal thresholds. This accounts for the almost half of preliminary injunctions that falter on appeal. The moral is clear: “fast and furious” does not guarantee “lasting and robust.”

V. Forum Shopping: Strategic Volume Control and Diversification

In light of these data, many users should have begun to rethink the reflexive strategy of “always going to Germany.” While Munich and Düsseldorf still command considerable attention, quieter divisions—Paris, Brussels, The Hague, and Milan—have demonstrated greater appellate consistency.

This evolution resembles portfolio diversification: by spreading filings across several UPC divisions, litigants can mitigate the volatility of appellate outcomes. Over time, as non-German divisions attract more caseload, their reversal rates may rise slightly—thereby rebalancing the system. Ultimately, forum selection must be driven by real performance metrics, not by outdated assumptions about any one country’s inherent advantage.

VI. Reappraising the “German” Image of the UPC: Lessons Learned

From the UPC’s inception, it seemed destined to become “German” for three reasons:

-

Germany’s high volume of patent litigation.

-

The presence of four local German divisions—the highest number among Member States.

-

A perception that some German judges might display a “pro-patentee” tilt, echoing certain high-profile US benches (Judge Albright, United States District Court for the Western District of Texas (Waco/Austin)).

In practice, however, three lessons have emerged:

-

No summit endures forever. Munich and Düsseldorf may have dominated early filings, but as data on appellate consistency accumulates, their comparative advantage diminishes.

-

First movers bear outsized risk. By defining the first wave of UPC jurisprudence, German divisions invited close appellate scrutiny. Correcting early doctrinal “drumbeats” was inevitable.

-

Market forces drive rebalancing. As other divisions prove reliable, litigants will diversify their filings. The myth of an enduring “German court” dissolves as real‐time data reshape strategy.

Practitioners should therefore allow empirical evidence—reversal rates, caseloads, judges’ expertise—to guide forum choice, rather than clinging to habit or reputation.

VII. Projections: One Year, Two Years—and Beyond

A. Methodology Explained Simply

To estimate how the UPC’s overall reversal rate might change over time, we use a straightforward idea: we blend Germany’s reversal rate and the reversal rate of all other divisions, weighted by how many cases each group handles. Here’s how:

-

Key Numbers

-

Germany’s average reversal rate: 30.4 percent

-

Non-Germany’s average reversal rate: 16.7 percent

-

-

Estimate Case Shares

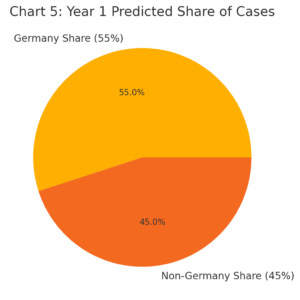

For each future year, decide what fraction of UPC cases Germany will handle. For instance, in Year 1, we assume Germany = 55 percent and all other divisions = 45 percent. -

Calculate Weighted Average

-

Multiply Germany’s rate (30.4 percent) by Germany’s share (0.55) → this gives the “Germany contribution.”

-

Multiply Non-Germany’s rate (16.7 percent) by Non-Germany’s share (0.45) → this gives the “non-Germany contribution.”

-

Add those two numbers to get the overall reversal rate for that year.

-

-

Repeat for Each Year

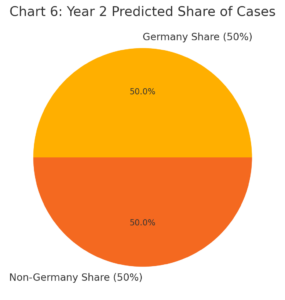

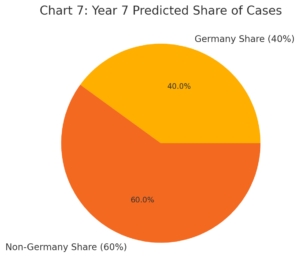

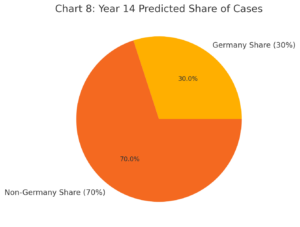

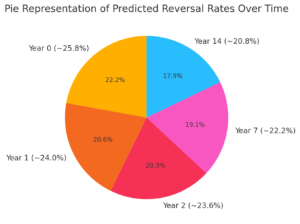

Change Germany’s share to 50 percent in Year 2, 40 percent in Year 7, 30 percent in Year 14, and so on. Always multiply each share by its respective rate, then add.

Concretely:

-

Year 0 (current): Germany = 60 percent, Non-Germany = 40 percent

-

Germany contribution: 0.60 × 30.4 % = 18.24 %

-

Non-Germany contribution: 0.40 × 16.7 % = 6.68 %

-

Overall reversal rate: 18.24 % + 6.68 % = 24.92 % (≈ 25.8 % if rounding to one decimal)

-

-

Year 1 (Germany 55 % / Non-Germany 45 %):

-

Germany: 0.55 × 30.4 % = 16.72 %

-

Non-Germany: 0.45 × 16.7 % = 7.52 %

-

Overall: 16.72 % + 7.52 % = 24.24 % (≈ 24 %)

-

-

Year 2 (Germany 50 % / Non-Germany 50 %):

-

Germany: 0.50 × 30.4 % = 15.20 %

-

Non-Germany: 0.50 × 16.7 % = 8.35 %

-

Overall: 15.20 % + 8.35 % = 23.55 % (≈ 23.6 %)

-

-

Year 7 (Germany 40 % / Non-Germany 60 %):

-

Germany: 0.40 × 30.4 % = 12.16 %

-

Non-Germany: 0.60 × 16.7 % = 10.02 %

-

Overall: 12.16 % + 10.02 % = 22.18 % (≈ 22.2 %)

-

-

Year 14 (Germany 30 % / Non-Germany 70 %):

-

Germany: 0.30 × 30.4 % = 9.12 %

-

Non-Germany: 0.70 × 16.7 % = 11.69 %

-

Overall: 9.12 % + 11.69 % = 20.81 % (≈ 20.8 %)

-

These projections rely on two simple premises: subgroup reversal rates stay the same, and Germany’s share declines over time. Real-world factors—changes in law, shifting doctrines, or strategic rebalancing—could accelerate or slow these transitions. But the pattern is clear: as Germany’s share of UPC filings decreases, the overall reversal rate drops.

In fact, imagine all cases as ingredients in a single recipe. German divisions taste “spicy” because they have about a 30 percent reversal rate, while the rest of the UPC tastes “milder” at roughly 17 percent. When Germany supplies 60 percent of the cases, the overall flavor is blended by taking 60 percent of 30 percent (about 18 percent) and adding 40 percent of 17 percent (about 6.8 percent), yielding an overall reversal likelihood near 25 percent. If Germany’s share falls to 55 percent, you mix 55 percent of 30 percent (about 16.5 percent) with 45 percent of 17 percent (about 7.65 percent), and the average drops to roughly 24 percent. If Germany’s share falls to 50 percent, blending half of 30 percent (15 percent) with half of 17 percent (8.5 percent) yields about 23.5 percent. In other words, as fewer cases come from the high-reversal German courts and more from lower-reversal jurisdictions, the combined reversal rate naturally declines.

Final Note: When Empirical Rhythm Overtakes Reputational Riffs

Heraclitus reminded us that “every summit carries within it the seeds of its descent,” and in UPC appeals this lesson rings true. If Germany’s share of UPC filings slides from 60 percent today to 30 percent in fourteen years, our simple arithmetic forecasts the overall reversal rate dropping from about 36 percent to roughly 20.8 percent. In other words, the data hits the right notes—even if our instincts hit false ones.

For patent litigators, the lesson is unmistakable: reputations fade, but data endures. As filings continue to diversify across UPC divisions, the aggregate reversal rate will smooth out. Forum selection must shift from reliance on legend to deference to empirical evidence—a tune that plays well in a truly pan-European orchestra.

And to close with a riff from Rammstein that illuminates this dynamic:

Wir warten auf das Licht.

(“We wait for the light.”)

In UPC litigation, that light is not a single spotlight but the shared illumination of a pan-European legal symphony.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Patent Blog, please subscribe here.

We also wait for the light in other ways not discussed by the author.

Of particular concern is the fact that most of the UPC’s decisions lack detailed chains of reasoning that start by identifying the legal provisions that are relevant, and that then interpret and apply those provisions.

For example, at what point will the UPC provide detailed reasoning on the NATIONAL law that applies to unitary patents, as per the UP Regulation? As far as I am aware, the UPC has so far simply ignored this issue in cases where it ought to have arisen.

Sadly, there are many other examples that I could give of missing, inadequate or incomplete reasoning in UPC decisions. I had expected the UPC to at least be thorough. Perhaps this will improve with time as well.