In this series, we will review the practice of the German Federal Court of Justice (Bundesgerichtshof or BGH, herein: FCJ) on key questions of patent law such as claim construction, added subject-matter, and patentability. This case law summary is intended for practitioners from all over the world, especially for those from outside of Germany. We will introduce settled case law and discuss recent decisions. Questions and comments, especially insights from our international colleagues are always welcome.

In German practice, claim construction is key. Thus, our series begins with the FCJ’s case law on claim construction[1].

A. General principles

The statutory basis for claim construction of a German patent is Section 14 of the German Patent Act and for the German part of a European Patent the legal basis is Art. 69 EPC.

According to settled practice, claim construction is a question of law that is within the responsibility of the court ruling on infringement (BGH, X ZR 103/13, GRUR 2015, 972 – Kreuzgestänge) and the court ruling on validity (BGH, X ZR 92/16). While generally, the claim construction of the different courts ruling on infringement and validity should not diverge, this principle does not take absolute precedence (BGH, X ZR 68/10, GRUR 2012, 93 – Klimaschrank). As for the UPC (see CoA_335/2023 / App_576355/2023), the same principles for the interpretation of a patent claim apply equally to the assessment of infringement and validity of a European patent. However, unlike in UPC infringement proceedings with a counterclaim for revocation, the German infringement and validity courts might arrive at a different result when applying those principles. Therefore, a divergence between the infringement and validity courts’ claim constructions is possible. Any party seeking to correct this has to appeal, meaning that claim construction may only ultimately converge at the FCJ.

B. Relevance of the description

German practice applies the principle of primacy of the patent claim. A technical teaching that is disclosed in the description, but which is not claimed in the claims, remains outside the scope of protection (BGH, GRUR 1980, 219, 220 – Überströmventil; BGH X ZR 20/86 – Rundfunkübertragungssystem). On the other hand, a broad patent claim cannot be interpreted restrictively by referring to the description; in particular, a claim is generally not limited to an embodiment described in the description (BGH, GRUR 2004, 1023, X ZR 255/01 – Bodenseitige Vereinzelungseinrichtung; BGH, GRUR 2007, 778, X ZR 72/05 – Ziehmaschinenzugeinheit).

Nonetheless, significant weight is given to the description when construing the claims. The description and drawings are in any case used for claim construction, i.e. not only in cases where a term in a claim appears ambiguous (BGH, X ZR 43/13 – Rotorelemente). The same approach is also applied by the Unified Patent Court (UPC 1/2023). The EPO’s practice regarding the relevance of the description for claim construction is subject to a pending referral to the Enlarged Board of Appeal (G 1/24).

In this post, we will examine the relevance of the cited prior art for claim construction.

I. Background

According to the settled practice of the FCJ, prior art citations and the way that the patent describes the prior art in the description can be relevant for claim interpretation insofar as the teaching of a patent seeks to distinguish itself from the prior art described in it (the UPC has so far applied similar principles, see LD Düsseldorf 31 October 2024, Sodastream v Aarke, ACT_580849/2023, ORD_598499/2023). In particular, if the disclosure of a known prior art document is equated with the preamble of a patent claim in the description, the features of the characterizing part are, in case of doubt, not to be interpreted such that they are disclosed by the cited prior art from which they are intended to be distinguished (BGH, X ZR 16/17, GRUR 2019, 491 – Scheinwerferbelüftungssystem). The same applies if in the description of a patent a known prior art document is described as disadvantageous and a feature provided for in the patent claim is emphasized as a means of overcoming this disadvantage (BGH, X ZR 17/19, GRUR 2021, 945 – Schnellwechseldorn).

However, this only applies if the prior art document is cited specifically in this regard; a vague reference is not sufficient (BGH, X ZR 44/20, GRUR 2022, 1129 – Verbundelement).

This can lead to situations in which a patent – that probably would have been revoked under a broad claim construction – is deemed valid but at the “expense” of a narrow claim construction.

II. Brenngutkühlung decision

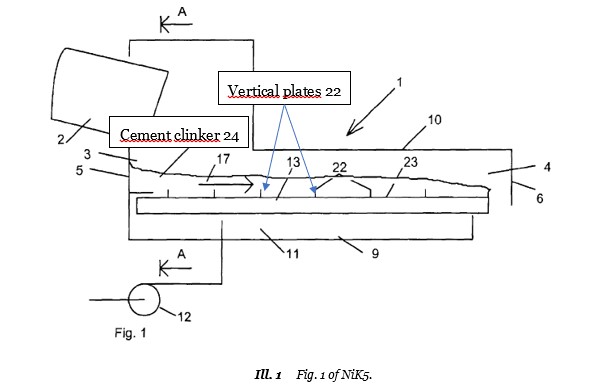

Building upon those settled principles, an illustrative decision relates to the European patent EP 1 509 737 B1 that concerns the cooling of “fired material”, e.g. cement clinker (BGH, X ZR 87/20 – Brenngutkühlung[2]). Claim 1 reads (English translation of granted claims as published):

“Method for cooling the fired material which emerges from a firing furnace as a layer of bulk material on the conveying grate of a cooler connected downstream of the furnace by means of a gas stream which is passed through the grate and the layer of bulk material from below, the grate comprising a plurality of planks which are elongate in a conveying direction and are driven to and fro in the conveying direction, and of which at least two adjacent planks are moved forward simultaneously and are moved back non-simultaneously, there being no conveying members above the grate, characterized in that there is a lack of vertical mixing movement in the layer of bulk material and the bed height on average is no less than 0.7 times the plank width.”

Of decisive importance in this case was the feature “lack of vertical mixing movement in the layer of bulk material” (feature 4).

1. Claim construction

The introductory part of the description referred to the prior art document DK 1999/1403 A (cited as NiK5 by the nullity plaintiff), which the patent acknowledged to disclose the known solution of a so-called “walking floor” (essentially the preamble of the claim). According to the introductory part of the description of the EP ‘737 patent, NiK5 discloses vertical cross walls[3] that are arranged on the planks of the grid, which move forwards and backwards with the planks in order to effect a vertical mixing motion of the fired material of NiK5.

However, according to the description of EP ‘737, a vertical mixing movement in the layer of the fired material is to be avoided so that the gas passes through the hottest layers last during a cooling process and therefore leaves the layer at a higher temperature than would otherwise be possible if there were more vigorous vertical mixing of the fired material. According to EP ‘737, this results in better heat recovery.

Thus, the FCJ found EP ‘737 considers a vertical mixing movement disadvantageous and that the lack thereof is to be construed as the distinguishing feature of the claimed subject-matter over NiK5. The FCJ concluded that feature 4 thus refers to mixing movements that can be caused by the vertical plates 22 of NiK5 and the vertical displacement generated by them. This further means that a vertical mixing movement is not absolutely prohibited by the claim. Instead, such movements are allowed if they are practically unavoidable due to the conveying principle defined by the claim (the “walking floor”). However, feature 4 is not realized if special measures are taken to promote vertical displacement, such as the vertical plates 22 as disclosed in NiK5.

2. Validity

In the first-instance, the Federal Patent Court had concluded that claim 1 lacks an inventive step in view of NiK5 as NiK5 would disclose the preamble and feature 4, and render the remaining part of the characterizing portion obvious. The FCJ overruled this judgement, instead finding that NiK5 does not disclose feature 4, given that feature 4 is to be construed such as to distinguish claim 1 over NiK5.

NiK5 considers a design without vertical plates 22 to be inefficient. Claim 1 was found inventive since EP ‘737’s key teaching is that this inefficiency can be resolved without the need for vertical plates 22 or vertical mixing.

III. Lessons learnt

As applicant/patentee: ultimately, this practice of the FCJ helps those applicants that know the prior art before filing and carefully define (even small) technical distinguishing features already at the drafting stage and explain technical advantages thereof in the description.

In contrast, in US practice to achieve a broad scope of protection, statements with respect to prior art documents are often avoided when drafting patent applications. As a consequence, an application drafted according to US practice (that then directly or via PCT enters the European/German route) would likely have a broader scope of protection under German practice but may lead to validity issues for prior art that is very close to the claimed subject-matter.

As alleged infringer/nullity plaintiff: if a patent cites a certain prior art document and if it is specifically explained in the description which claimed features are meant to distinguish the subject-matter from that prior art document, based on the principles discussed above, the claim might be construed such that that feature is not disclosed by the cited prior art document. The claim may thus be found at least novel over that cited prior art. On the other hand, if the accused product insofar corresponds to the disclosure of the prior art document, based on the above principles, the claim might be construed such that the accused product does not to infringe (for the UPC perspective and the UPC’s findings on the so-called Gillette defense, see LD Düsseldorf 31 October 2024, Sodastream v Aarke, ACT_580849/2023, ORD_598499/2023, section V).

—————————————————————————————————————————–

[1] Decisions are available in German free of charge at: https://juris.bundesgerichtshof.de/cgi-bin/rechtsprechung/list.py?Gericht=bgh&Art=en&Sort=3

[2] http://juris.bundesgerichtshof.de/cgi-bin/rechtsprechung/document.py?Gericht=bgh&Art=en&Datum=2022-9&Seite=2&nr=131679&anz=266&pos=63

[3] The EP ‘737 patent used a slightly different terminology than the translation of NiK5 (vertical plate) but this was deemed irrelevant.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Patent Blog, please subscribe here.