In case you missed it, here are the main points from the EPO Boards of Appeal Case Law Conference 2024. As ever, this was a really interesting event with lots of high quality presentations. Above all, it is great to hear at first hand what the Board members themselves think of the hot topics at the EPO.

Update on Board of Appeal Timelines – Carl Josefsson

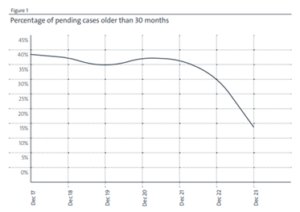

As usual, the President of the Boards of Appeal was first up. He highlighted the improvements in statistics on timeliness:

- As of June 2024, less than 10% of cases are older than 30 months.

- By the end of 2025, they predict that there will be no more than 10% of cases older than 24 months.

Although no detailed statistics were presented, these figures generally seem in line with the trend in figure 1 of the 2023 Annual Report of the Boards of Appeal:

These are of course welcome developments, it is only a shame they are not accompanied by similar statistics relating to quality.

Highlights of Recent BoA Case Law – Karel Peirs

Sufficiency: Over the Whole Range Comes to Mechanics

This presentation looked at various aspects of claim construction. Mr Peirs highlighted that the debate continues on whether sufficiency requires that the skilled person is able to carry out the invention “Over the Whole Range”, or if showing “at least one way” suffices.

While traditionally applied in chemistry (see e.g. T 500/20 r 3.6), recent decisions (e.g., T149/21, T553/23) suggest that the requirement to demonstrate sufficiency across the whole claim scope (i.e. in all technically viable contexts, but not including unusual circumstances like a nuclear strike) is increasingly being applied for mechanical inventions. No doubt music to the ears of opponents in this field.

Adaptation of the Description: Should It Stay or Should It Go?

Adaptation of the description was also touched upon by Mr Peirs, with both T56/21 and T438/22 briefly discussed. He didn’t go further than accepting that there is a divergence, which is more than can be said of T56/21 itself! See our earlier post on this: Kluwer Blog Article: La Zizanie de l’OEB sur l’Adaptation de la Description).

G2/21 – Marcus Müller

The meaning of G 2/21 continues to confound many practitioners. As such, Mr Müller’s detailed explanations of the key points in several recent decisions applying G 2/21 were welcome.

First several decisions were presented that applied the G2/21 test and allowed post-published evidence when assessing inventive step (T1525/19, T1989/19, T840/22, T2716/19, and T681/21 AR4). Then, several decisions in which post-published evidence could not be relied upon were discussed (T681/21 (MR), T887/21, T1994/22), with T681/21 acting as a useful bridge, as it permitted the evidence for some requests not others. We have commented on some of these before, see e.g. – Trying to Make Sense of the Oracle of G2/21: T116/18 vs. T681/21.

Particularly interesting were the cases dealing with a very common scenario – where post-published evidence is filed to show that a first alternative disclosed as part of the original invention delivers an improved technical effect relative to a second alternative also disclosed as part of the original invention. T840/22 held that this was “precisely what regularly occurs in patents/patent applications in the field of chemistry” and allowed the reliance on the new data. On the other hand, T852/20 didn’t permit reliance on new data in what seemed from Mr Müller’s presentation to be a similar scenario.

We are also grateful to Mr Müller for providing his own “personal summary” on how to understand the seemingly divergent cases following G2/21. Based on our understanding from the lecture, it is his view that:

- There is no true divergence in decisions; apparent inconsistencies are due to differences in the details of the cases;

- It is important that it is clear that the effect is essential to the invention and tied to the claimed subject matter;

- If 2 is met, post-published data can generally be used for inventive step unless there are legitimate doubts;

- If an effect can be relied upon, the improvement can be relied on too;

- There is no need for verbatim basis for the effect;

- Sweeping statements of effects may be not be enough though in themselves;

- Patentee will struggle if there is an inconsistency between the teaching of the application as filed and the mechanism of the effect they later rely on.

Of course, the first thought when analysing these is to question whether they are entirely consistent, emphasising on the one hand the lack of need for verbatim effect but criticizing sweeping statements on the other. Presumably though this comes down to the context-dependent first point, and particularly the role the different common general knowledge may play in leading to different decisions in similar scenarios. While these points may therefore be difficult to use to reliably predict the outcome of any specific case, it is very useful to know which are considered to be the key elements.

Image taken from commons.wikimedia.org

Rules of Procedure of the BoA (Four Points of Divergence) – Kemal Bengi-Akyürek and Jeannine Hoppe

This was another tour de force of a presentation – with a wide variety of points of divergence in application of the RPBA identified by the speakers. The points where different boards have applied these strict rules in different ways were as follows:

Pre-emptive Strikes

Should an opponent already comment in the grounds of appeal on requests filed in the first instance that were not part of the opposition division decision? Divergent decisions T2035/16 and T664/20 were discussed (on this topic, see also the HE Quarterly of September 2024: Inconsistencies in the Application of the EPO Rules of Procedure of the Boards of Appeal Concerning Case Amendments).

Carryover Requests

These are requests on appeal that were filed before the first instance but no decision on admissibility was reached in the first instance decision. Mr Bengi-Akyürek discussed these at length.

It was first highlighted that Rule 12.4 RPBA gives the applicant the burden to show that these were “admissibly raised and maintained” in the first instance. Three different approaches to how the boards deal with such requests were identified.

- T364/20: the board steps into the Opposition Division’s shoes to evaluate admissibility, and has no discretion not to admit if the OD should have admitted (r.7 of the decision) (on this point see also: The meaning of “admissibly raised” in Article 12(4) RPBA).

- T1800/20 headnote: this applies a similar approach, but in reaching the decision weighs up different factors such as timing, suitability to overcome objections, convergence, and whether new issues are raised.

- T246/22: again applying different factors to reach the decision, by suggesting a “minimal test” of whether the request and the purpose of the request were filed in due time in the first instance. If so, admissibility on appeal can be addressed using the RPBA to decide whether they are admitted. Contrary to T 364/20, T246/22 advises against stepping into the Opposition Division’s shoes (r. 4.13).

While different factors are applied when deciding on these carryover requests, it seems clear that filing requests without due substantiation is a risky business, regardless of the stage of the proceedings.

The third stage of appeal proceedings

Two different aspects of divergence were identified concerning the third, strictest stage of the appeal proceedings.

Concerning Rule 13.2 RPBA, it was accepted that there is divergence as to whether procedural requests can even be held inadmissible (On this point, see also: Kluwer Blog Article: T1006/21).

Meanwhile, two different approaches for assessing the Rule 13.2 “exceptional circumstances” test were discussed: it seems that some decisions take a more lenient approach (T2295/19, T339/19, T2604/18), as they don’t require the amendment to have been caused by the exceptional circumstances, just that exceptional circumstances are generally present in the case. Meanwhile, we understood that other decisions – like T2482/22 or T1558/22 – take a stricter view and require a causal link between the exceptional circumstances and the amendments.

A final word

As many of the cases above point to some degree of divergence between the Boards, we found the general discussion of the Board Members Kemal Bengi-Akyürek and Jeannine Hoppe in the questions section particularly interesting.

The perennial issue of divergence between boards had been raised in a question, with a comparison between Boards of Appeal decisions and a “lottery” being drawn. As expected, the Board members strongly defended their decision-making process on several points, not least that the decisions in the end are generally well-reasoned and not entirely arbitrary like a lottery. They also took the view that some divergence is a normal step on the way to adopting a uniform application of the law, and is even something that arises from the EPC referring to a plurality of Boards.

We have some sympathy with these explanations and the difficulty of ensuring complete consistency across the large number of decisions issued each year. But they will be cold comfort to parties who have had the bitter experience of losing patents or oppositions due to the interpretation of the RPBA adopted by the particular Board they find themselves before.

But, as Bengi-Akyürek put it, “that’s life”, calling to mind the lyrics to Frank Sinatra’s famous song…

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Patent Blog, please subscribe here.