We have long meant to write something about the need, or the lack thereof, for adapting the description to amended claims. The announcement in the second preliminary opinion of Technical Board of Appeal (TBA) 3.3.04 in T 56/21, suggesting a referral of this question to the Enlarged Board of Appeal, combined with the sole appellant’s agreement with such a referral and perhaps a modicum of personal inertia, has kept us from it. But meanwhile we know that things took a different turn: in short, TBA 3.3.04 had second thoughts about a referral and instead issued a whopping 86-page decision explaining and justifying its firm opinion that neither Art. 84 EPC nor Rule 43 EPC provide a legal basis for a mandatory adaptation of the description, and that Rule 48 cannot be used as a basis for a refusal of a European patent application. The applicant may, however, amend the description of its own volition.

In other words, according to Board 3.3.04 the description no longer needs to be adapted to any amended claims, and requesting an amended description would even contravene the EPC. In view of the fact that the current Guidelines for Examination, Chapter H-V 2.7 explicitly require that:

The description must be brought into line with amended claims by amending it as needed to meet the requirements set out in F-II, 4.2, F-IV, 4.3(iii) and F-IV, 4.4.

and threaten the applicant with this:

If the applicant does not amend the description as required despite being asked to do so, the examining division’s next action may be to issue a summons to oral proceedings; for the time limit, E-III, 6(iii) applies

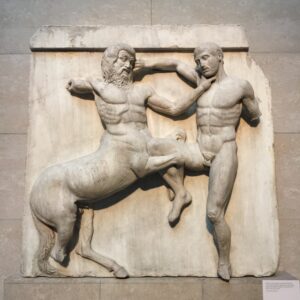

we seem to be entering interesting times with this decision. By the way, the French word “la zizanie”, which we borrowed from Asterix Vol. 15 (German title “Streit um Asterix”, English: “Asterix and the Roman Agent”), means “discord”. The ancient Athenians illustrated it like this

(own picture – note that we are not taking a position on which Boards are the Lapiths and which the Centaurs)

How will cette zizanie within the EPO be resolved? That’s the big question.

Might the EPO legal division act?

Of course, the EPO’s legal division may simply take this decision at face value, delete Chapter H-V 2.7 from the Guidelines (and similar sections elsewhere, e.g. in Chapter F-IV, 4.3 and 4.4) and the other Boards of Appeal may adopt the reasoning of T 56/21. This would be a simple way to achieve harmony within the EPO and legal certainty for applicants (at least with respect to the procedure; whether the patents thus granted would also enjoy a higher legal certainty may be left for another discussion). And most applicants and representatives would probably rejoice. Adapting the description is tedious, dull and certainly among the least-loved activities of a patent practitioner. And it takes a lot of time and is, hence, expensive. Add to this the fact that the United States Patent and Trademark Office never requires the description to be adapted, yet patent enforcement obviously works there as well, and you may arrive at the conclusion that there is certainly no “business case” for the adaptation of a description if the claims are amended.

But we doubt that this is where things will go. For a start, the Board at reason 6 go out of their way to explain that no adaptation of the Guidelines is required, despite the fact that the examining division referred to and applied these when refusing the application. Add to this the fact that at the first instance level, we have observed exactly the opposite trend: the Guidelines for Examination have repeatedly been supplemented with more and more paragraphs stipulating that the description must be amended and specifying cases where such an amendment must be required. For example, the above quoted Section from Chapter H-V 2.7 cannot be found in the Guidelines of 2009 or of 2013. The closest paragraph in the 2009 Guidelines is this:

C-VI-13 (iii) Agreement of description and claims

If the claims have been amended, will the description require corresponding amendment to remove serious inconsistency between them? For example, is every embodiment of the invention described still within the scope of one or more claims? (see III, 4.3). Conversely, are all of the amended claims supported by the description? (see III, 6). Also, if the categories of claims have been altered, will the title require corresponding amendment? It is important also to ensure that no amendment adds to the content of the application as filed and thus offends against Art. 123(2), as explained in the following paragraphs.

This sounds considerably more pragmatic and allows the examiner more discretion than current H-V 2.7. In addition, the catalogue of cases in which objections under Art. 84 EPC should be raised has also been expanded over the past couple of years. Thus, for the EPO’s Legal Division, following the rationale of T 56/21 would certainly mean a complete U-turn.

How might the other Boards respond?

We may be wrong, but we are also sceptical whether other Boards will (completely) follow T 56/21. The decision itself lists quite a number of recent cases in which other Boards have taken a partially or completely different position than Board 3.3.04. The Board acknowledged on page 85 of its decision that “it could be argued that there are diverging decisions”, but went on to postulate that

it is rather more the case that the practice is evolving (compare T 433/21, point 8.4 of the Reasons, advocating a non-coercive discourse) taking into account the revision of the EPC in 2000 and developments thereafter (in particular the acknowledgment of equivalents in the Protocol and the negotiations on a supranational court for infringement and nullity proceedings).

While we certainly agree that the Board’s practice is evolving, we are not convinced that it is evolving in the same direction. For example the Boards in both T 3097/19 (published less than 2 years ago in November 2022) and T 438/22 (published less than 1 year ago in November 2023) were certainly able “to take into account the revision of the EPC in 2000 and developments thereafter (in particular the acknowledgment of equivalents in the Protocol and the negotiations on a supranational court for infringement and nullity proceedings)”, but came to different conclusions, i.e.:

“The purpose of the claims to define the matter for which protection is sought (Article 84 EPC) imparts requirements on the application as a whole, in addition to the express requirements that the claims be clear, concise and supported by the description. The Board deems it to be an elementary requirement of a patent as a legal title that its extent of protection can be determined precisely. Whether this is the case for a specific patent application (or an amended patent) can only be decided with due consideration of the description. Claims and description do not precisely define the matter for which protection is sought if they contradict each other (…). ” (T 3097/19, headnote 3).

And

“It is a general and overarching objective, and as such also a ‘requirement’ of the Convention, that authorities, courts, and the public interpreting the claims at a later stage should, as far as possible, arrive at the same understanding of the claimed subject-matter as the EPO bodies deciding on the patentability of the same subject-matter. The only tool for achieving this objective is the patent specification as the expression of a unitary legal title. The description, as an integral part of the patent specification, should therefore also serve this overriding objective, i.e. it should provide a common understanding and interpretation of the claims. If the description contains subject- matter which manifestly impedes a common understanding, it is legitimate to insist on its removal under Articles 84 and 94(3) EPC and Rules 42, 48 and 71(1) EPC. ” (T 438/22, headnote 2).

Thus, it appears that TBA 3.4.03 in T 438/22 and TBA 3.5.06 in T 3097/19 take a fundamentally different approach that includes the presumption of a close connection of the claims and the description, both of which form “a legal title” or “a unitary title”, i.e. the patent or patent application. As a corollary of this understanding, the description will always have to be considered when determining the claimed subject-matter. TBA 3.3.04 strongly disagrees with this understanding and considers that the description is not to be used when checking the requirements of Art. 84 EPC, because the latter solely pertains to the claims, not the description.

Thus, while it is not impossible that TBA 3.4.03 and TBA 3.5.06 will perform a legal about-turn and throw their support behind 3.3.04’s approach, it seems unlikely. Striking in this regard is that, to our knowledge, all decisions dispensing with the need to adapt the description have originated from Boards having the same legal member, Mr. Lukas Bühler.

Why was there no referral?

Given the above, in our view it is surprising that TBA 3.3.04 decided not to refer the case to the Enlarged Board in their decision. What stopped them? At reasons 101 – 104, the Board held that no referral is necessary since:

1) Article 84 is unequivocal in not requiring adaption;

2) Reasons for the traditional EPO practice of requiring this aren’t convincing;

3) The lack of legal requirement for adaptation appears intentional; and

4) There is no divergence, only an evolution of case law on this issue.

These reasons are rather difficult to follow. Even if TBA 3.3.04 are personally convinced of 1), they should at least accept that this is a pretty hotly contested point between themselves and other Boards, as evidenced by T 3097/19 and T 438/22. The same goes of course for 2): other Boards have set out what they consider to be convincing reasons for adaptation. 3) is also clearly disputed, since other Boards have taken the view that Art 84 EPC implies or at least supports a legal requirement to adapt. In any case, surely a lack of legal requirement for adaptation should speak for a referral, when this is the practice required by the EPO in tens of thousands of communications each year! All of this undermines 4), as there is in our view no doubt that there is divergence, at the very least on the issue of whether the EPO can require adaptation.

We wonder then whether some other factor stopped the members of Board 3.3.04 taking this to the next level. It can of course not be excluded that the Board discussed its decision with other Boards beforehand and wished to express an emerging common view among the Boards, but we do not view this as overwhelmingly likely. Perhaps it was felt that other Boards should first have a chance to consider TBA’s 3.3.04 comprehensive and extensive argumentation before possibly referring this matter to the Enlarged Board in case they really disagreed therewith. Perhaps strategic considerations stayed their hand: if other Boards weren’t following 3.3.04, what hope would there be of a decision in their favour from the Enlarged Board, itself made up of legal members of the Boards? Or maybe they felt that a referral decision being so emphatic and detailed as T 56/21 would look like they were trying to do the Enlarged Board’s work for them? We’d be interested to hear any theories you might have in the comments below. Oh to be a fly on the wall of the Café in Haar!

Whatever the reason, T 56/21 leaves EPO Users with considerable legal uncertainty, at least for the time being. Our present impression is that adaptation will continue to be generally required by most EPO examining and opposition divisions, unless more Boards show that they agree with the position taken in T 56/21. Under these circumstances, the only way to avoid an adaptation of the description is to get a refusal on this issue, appeal, and hope that your legal member is Mr. Bühler (who has been involved in all of the decisions questioning the legal basis for the existing practice)!

Our view on the requirement to adapt the description

Even though we mostly agree with the result reached in T 56/21 that an adaptation of the description should normally not be required, we have problems following a lot of the Board’s reasoning, in particular where the Board postulated that the description should not be considered when interpreting the claimed subject-matter. However, we will leave this issue to the Enlarged Board in G 1/24.

Art 84 is indeed mainly directed at the claims. They shall be clear, concise and supported by the description. Nonetheless, the question whether the claims are clear can only be answered after their subject-matter has been understood by the skilled person, and it seems self-evident to us that the primary basis for the skilled person’s understanding can only be the patent (application) as a whole, including its description. To exclude the description as a source when forming this understanding seems awkward to us, not least because it violates the EPO’s own rule that interpretation of any document requires examining its whole disclosure.

Does this mean that claims will always be clear, because the skilled person will have understood their subject-matter after having carefully read the description and construed the claims with a mind willing to understand (T 190/99)? Certainly not. There will still be cases where the claims are in apparent contradiction with the description, and there may also be cases where the description offers contradictory or unclear explanations of the terms of a claim. In these cases, an Art 84 EPC objection can and should be raised. Conversely, in cases where a claim as such might be understood in two ways, but the description clearly explains which way is meant, we see no compelling reason for a clarity objection. The description can and should be used as the patent’s dictionary.

What follows from these first principles if a claim has been amended (limited)? Firstly, we think that the amended claim must of course be clear, when viewed together with the description. Any remaining unclarity should be removed, which can be accomplished either by further amending the claim, or – at least in some cases – by amending the description, particularly if the unclarity only arises due to a contradictory or unclear definition of a term which is (also) used in the claim.

Beyond this, however, we see little justification for requiring an adaptation of the description. In particular, the support requirement in Art 84 should not be misused for requiring the description to be co-extensive with the claims or for requiring a deletion of examples that no longer fall under the amended claim. The ancient Athenians might have expressed this scenario in the following terms.

Suppose the application as filed disclosed and claimed a peripteral octastyle Doric temple with 46 outer columns such as this one:

(All pictures taken from: Maxime Collignon (1849-1917), Le Parthénon: l’histoire, l’architecture et la sculpture, Paris 1914. Online Version available here.)

The application to this temple had to be amended a couple of times for historical reasons. First, a church dedicated to the Virgin Mary and then a Mosque with a Minaret were erected within this temple (both amendments clearly violating Art 123(2) EPC). In 1687, the Parthenon was misused as a gunpowder magazine to defend Athens against a Venetian military expedition (arguably violating both Art 53(a) EPC and Art 123(2) EPC). This resulted in big destructions when a Venetian cannon ball hit the magazine. From 1800 to 1803, the 7th Earl of Elgin removed several of the sculptures to London (Art 123(2) EPC again). Any remaining Christian and Muslim additions were removed again in 1832, once Otto I, brother of the Bavarian King Ludwig I (and like him an ardent admirer of classic Greek art), became King of Greece. As a consequence, the status in the early 1900s was as shown above and below. Only about 31 of the original 46 outer columns were still standing.

Let us assume that the applicants were happy with an amended claim directed at a doric temple with only 31 columns and finally wanted their patent on this basis. In our opinion, it would then be utterly unreasonable to request from the applicants to remove the (perfectly fine and elaborate, see above and here) support for the remaining 15 columns (which are now no longer claimed) from the description. Or, to put it in simple words, we see no compelling reason why the description should not be allowed to include more support than specifically needed for the claim. As long as the claim remains clear and has (at least) the support it needs to be understood and enabled, no objection under Art 84 EPC should arise. We also see no legal basis for requesting the applicant to designate the support for the unclaimed columns as “not according to the invention”. Both the public and the infringement courts will be able to recognize that the claims as originally filed were amended and to conclude therefrom that not all “embodiments” of the description are necessarily also covered by the amended claims.

Thus, some common sense and a somewhat restrained application of Art 84 EPC, which mainly focuses on removing apparent unclarities, might well yield about the same result as T 56/21 but with a much less dogmatic approach.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Patent Blog, please subscribe here.

It is not the Legal Division that is responsible for the Guidelines (but they do art.20 EPC)… but the Directorate Patentlaw and Processes | Dir. 5.3.1

“Both the public and the infringement courts will be able to recognize that the claims as originally filed were amended”- I thought German courts do not consider the file wrapper as a means of claim interpretation? Can we be absolutely sure that all courts in all EPC contracting states are willing to consider the prosecution history?

You do not need to consult the prosecution file to note that the claims have been amended. A comparison with the published application suffices. As far as I know, the German courts are willing to do that.

Thanks. The application as filed is not mentioned in Article 69 as a means of interpretation, just like the file wrapper is not, but perhaps a German reader could explain that.

Since the application as filed is not mentioned in Article 69 EPC as a means of interpretation, we cannot assume that national course in all EPC contracting states will consider it. The German example illustrates that even if it is possible for a court, in practical terms, to consider some information that is available publicly online (the file wrapper), it may be legally impossible for national courts to do so in proceedings.

If I did not know any better, I could swear that you are advocating for “strict” description amendments purely on the grounds that they help to ensure that national courts “correctly” interpret the claims. But that cannot be correct, as what happens with patents in post-grant (national) proceedings is beyond the EPO’s remit and therefore not their concern.

Dear Thorsten,

As far as “zizanie” is concerned, I would rather think that board 3.3.04 (and some odd other one) has started stirring trouble by adopting a position which is at odds with that of the vast majority of the boards.

It will not come as a surprise that I disagree with your point of view. I am also prepared to take a bashing as it happened in my own blog and in other ones.

I will be able to agree with you, like with all other people advocating no amendment to the description, the day the portion of Art 84 relating to the support of the claims will be deleted and that prosecution file history will become a means of interpreting the claim.

The UPC LD Munich has tried to use file history to interpret the claim in the Hanshow case, but the CoA UPC did not accept it and made clear that Art 69 and Art 1 of the Protocol are the correct means for interpreting a claim.

If even the CoA UPC does not want to hear about file history, why should the EPO leave the description as it was originally filed and accept an implicit file wrapper estoppel. In countries in which the description cannot be amended, file wrapper estoppel is the means of choice. You cannot have your cake and eat it.

I always give two examples in which the description ought to be adapted.

The first example is when a feature disclosed in the description as being optional is used to limit an independent claim. As Art 84, support, requires, this feature cannot be left as optional in the description. There would be a clear contradiction between the amended claim and the description if the latter would not be amended.

For the second example I will use your image of the Parthenon. If the original description disclosed 42 columns and in the end, i.e. after examination, only 36 columns can be left, where is the problem in acknowledging that the 6 columns which are not any longer part of the building do not belong to the invention as claimed? Leaving the impression that 42 columns might be encompassed by the invention is in flagrant contradiction with the amended claims. I would not require to delete the fact, that originally 42 columns were disclosed, but 42 columns do definitely not belong to the claimed invention.

The claims can also be defined as a protected perimeter. This perimeter is generally reduced following examination. Where is the problem in acknowledging that part of the original perimeter had to be given up during examination? I would also not require any reference to the original perimeter to be deleted, but the description cannot leave the impression that the amended claims still encompass the original perimeter.

As far as claim-like clauses are concerned, they are often used to paraphrase the originally filed claims and are purposedly left in the description. They do not help the understanding of the invention after examination and there is no reason to keep them in the description at grant. It is thus legitimate to delete those.

I have personally doubts that other boards, beside some very specific ones, will adopt the position taken in T 56/21. Should board 3.3.04 have decided to refer some questions to the EBA the situation might eventually be different. The EBA could decide, for instance with reference to a dynamic interpretation of the EPC, that the description ought not to be adapted to amended claims, but we are far from there… .

As far as the decision is concerned, I commented it in my blog. There is a lot to criticise in the decision. It is not convincing for a lot of reasons as I have explained there.

One of the most important point is the timing of the publication. The decision by dealing with the application of Art 69 and Art 1 of the Protocol during procedures before the EPO has directly an unambiguously encroached on the decision to come under G 1/24.

I do however agree with the decision in that Art 69 and Art 1 of the Protocol should not be used during prosecution before the EPO. The only exception is when it is necessary to check, in opposition, the conformity of the claims with Art 123(3), and even then not in the manner suggested in the Protocol. This is for infringement proceedings.

By bringing in G 2/12, the board has shed light on a much more recent decision of the EBA than rather than G 2/88 and G 6/88 used in the referring decision T 439/22 to propose in Reasons 6.2 and 6.3 a new way to examine applications and patents. This proposal boils down to adopting the German practice (Auslegung) of systematically interpreting claims before taking any decision.

I am not convinced that this is the way the EPO should followed in the future. This is the more so, since the EPO, for historicl reasons, is not competent to decide on the interpretation of claims in infringement.

I find myself in complete agreement with Daniel (as is often the case – I’ll get my part of bashing, Daniel, you’re not alone). As to Art. 69 EPC, although the board in T 56/22 did not analyse the travaux préparatoires and other historical material, there is abundant evidence that Art. 69 EPC was included in the Convention as part of the so-called “maximum solution” to define common rule to be applied *solely post-grant* (these rules are hinted at in the second recital of the Preamble to the EPC: “…by the establishment of certain standard rules governing patents so granted”. Art. 69 EPC was included in the EPC with the sole purpose of giving national courts a common rule for interpreting the claims in infringement proceedings *after grant*. There is not the slightest hint, in the travaux or elsewhere, that Art. 69 EPC was meant to be applied in proceedings before the EPO. I suggest taking a look at BR7/69, nr. 45, M/18, nr. 7, M/18, nr. 13 (as concerns the TP) or reading the illuminating passage on pp. 65-66 of the “Studie Haertel” where K. Haertel, in discussing the idea (based on a provision of Austrian patent law) of entrusting the EPO with ascertaining the extent of protection wrote the following: “Das … würde eine nicht unerheblich und auch nicht ganz folgerichtige Ausweitung der Zuständigkeit des europäischen Patentamts über das Erteilungsverfahren hinaus auch auf den Verletzungsprozeß mit sich bringen und würde das europäische Patentamt mit einer *seinem Wesen als Erteilungsbehörde fremden Aufgabe* belasten”.

Dear Alessandro,

Thanks for your comment. Be assured, even alone, I would stand for my opinion.

It will come out later, but I have written an amicus curiae for G 1/24 and the thrust of my argumentation is based on the travaux préparatoires, with copies of them. For historical reasons, the failure of 4 drafts of a convention on EC patents, and the upcoming of the PCT, it was necessary for European countries to get forward if they wanted to avoid the duplication of efforts when trying to get a patent granted in a plurality of European countries.

It led to what is known as the Haertel compromise. On the one hand, the opening of the future convention to non-EC states, e.g. CH, AT, SE or TR, and on the other hand to the separation of the grant procedure from the infringement procedure. This is an aspect which has been ignored, although I mentioned it a few times in comments on various blogs.

This is to me a reason good enough not to come up with requiring the EPC to interpret the patent as it would be done by a national court. It might well end up with different decisions as to the validity, as the interpretation of the EPO cannot be the same as that of a national court looking at infringement. This is however the direct consequence of the way the EPC was designed.

Please provide a link to your blog article.

Dear Thorsten,

In T 2119/19, the opponent appealed the rejection of the opposition. The patent was maintained on the basis of AR2=claims 1+2 as granted.

In order to support my plea for adapting the description in case of an optional feature incorporated in an independent claim, I would like to draw the attention to said decision.

I quote Reasons 2.2:

“The appellant=opponent argued that some passages of the description presented the pump as optional.

The Board agrees that the description has not been adapted to the claims of the second auxiliary request.

However, the adaptation of the description is a task that can be performed by the Opposition Division after a claim request has been found allowable. In such a case it may be appropriate for the Board to remit the case to the Opposition Division (Article 111(2) EPC) with an order to maintain the patent on the basis of this request and a description to be adapted thereto.”

What else is there to be sai?

“Adapting the description … takes a lot of time and is, hence, expensive” -> it would be helpful if the authors could elaborate on this. Adding the phrase “not according to the claims” a few times in the description does not seem very difficult or time-consuming. Furthermore, it may be unclear why this is not a suitable task for junior colleagues with perhaps a lower rate. It is not entirely clear to me if the costs of this final round of editing are significant compared to the total costs of the patent procedure?

In addition, applicants do not always seem happy if the EPO (Examining Division) does the job itself at no cost to the applicants. Can we be sure that the (perceived) costs for applicants are the only reasons for the complaints? If there is no harm to the applicant, why is there a debate about the legal basis for the service provided by the Examining Division of adapting the description to the amended allowable claims?

Perceiving the amendments of the description as “tedious, dull and certainly among the least-loved activities of a patent practitioner” might be subjective and, again, does not apply if the Examining Division makes the edits themselves. In any event, the EPO may consider legal certainty for third parties and high-quality patent grants somewhat more important than patent attorneys’ job fun.

Wiggleroom, it is clear that adapting the description is not an exercise that you have ever undertaken in the context of worrying about what might happen if you get anything wrong.

There may be some instances where there is little doubt that a specific disclosure of the description is “not according to the claims”. However, in many other cases, including some that might look clear-cut at first glance, it would be negligent not to ask yourself questions such as:

(1) Am I absolutely 100% confident that this is “not according to the claims”?

(2) What subject matter is encompassed by the claims, as correctly interpreted?

(3) Could I inadvertently add subject matter by amending the description, for example simply by presenting the invention in a context that is not precisely in accordance with the disclosures of the application as originally filed?

More often than not, at least one of these questions will have an answer that is neither simple nor straightforward. Indeed, until the EBA provides its answer in G 1/24, this is certain to be the case for question 2.

There seems to be a perception within EPO circles that “there is no harm to the applicant” when Examining Divisions insist upon stringent amendments to the description. However, as will be evident from the three questions above, this simply reflects the fact that EDs do not have to worry about what possible harms might arise post-grant … and so simply lack the imagination and empathy required to spot what is glaringly obvious to those of us on the other side of the fence.

Thanks. I note that your concerns are quite different from the ones expressed by the author of the original blog post.

It might be helpful if you could specify the risks under (3).

I mean, for item (1), I would say: fair enough, and it is only good that you check if the claims are as broad as the client wishes before grant – now you can still recommend filing a divisional. The EPO may see this as a legitimate part of the job of a patent attorney.

I assume you are thinking about Article 123(2)? Or point me to literature where the risks are set out in detail and illustrated with examples. It may be difficult to see (for the EPO) how adding a formal/simple phrase like ‘not according to the claims’ could add technical information in a way prohibited by G 2/10. Moreover, is there a risk of an Article 123(2) / (3) trap?

Wiggleroom, unlike the EPO, national courts are apt to interpret the claims in the light of the disclosures of the description. Adding the phrase “not according to the claims” thus invariably creates a risk of added matter, for example if a national court disagrees with your analysis and therefore perceives the added phrase as:

(a) having no basis in the application as originally filed; and, potentially

(b) representing an unallowable disclaimer of subject matter that would otherwise be encompassed by the claims.

I think that you will appreciate that, where (b) applies, an inescapable trap is created.

Personally, I do not see what would be wrong with specifying what the invention IS (ie according to the claims) instead of what it is not. That should be clear enough for all concerned. Unlike the EPO’s current practice, it also has the advantage of clear legal basis, namely the first sentence of Article 69(1) EPC.

Whilst it concerns description amendments that were made post-grant, as opposed to pre-grant, the 2023 UK High Court decision in Ensygnia v Shell (https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Patents/2023/1495.html) illustrates how (b) could arise in practice.

“201. It follows that a non-electronic sign or display did not fall within the scope of claim 1 as granted, but now falls within the scope of the claim as amended post grant. As a result, the protection of the Patent has been extended by an amendment which should not have been allowed and is invalid for this reason”.

@ Concerned Observer,

Give me one example in which a national court has revoked a European patent under Art 123(2) because of the adaptation of the description, when it later came to assess the validity of it? I have asked for it many times, but never saw an example.

The “Ensygnia” case relates to a UK patent and is therefore not directly applicable to European patents. It is the only example in which the adaptation of the description was detrimental to the proprietor and not because of added matter, but because of extension of scope. However, under the principle of party disposition, it is the applicant/proprietor which is to blame and not the patent office.

As far as amendments “free of charge” by the ED, when issuing the R 71(3) communication, EDs are often going to far and it is correct when applicants do not accept such amendments.

@ Wriggleroom,

In your comment about amendments “free of charge” by the ED, when issuing the R 71(3) communication, I perceive some tongue in cheek.

Only minor amendments should be carried out at the R 71(3) communication stage. Amending the description to bring it in conformity with the claims, or even more amending the claims, goes way beyond a minor amendment.

I have been too long in the business not to know that it is a form of twisting the arm of the applicant. I give you a patent immediately, but you have to accept the form I consider right. This is not correct and it is right when applicants complain. If applicants accept the amendment and it turns out later to boil down to added matter, it is the applicant/proprietor which will have to bear the consequences.

I do not put the blame on examiners. If they would have more time to deal which each case, they would not have to use such questionable ways to get their production figures.

It is however difficult to see how deleting the optional character of a feature in the description and acknowledging that some embodiments are not covered by the claims is leading to added matter.

To be honest, there is a bit of bad faith on both sides.

I don’t intend to be tongue-in-cheek in cheek in the text of my comments, but I think the analysis in the original post is incomplete. People discuss exclusively the allegedly lacking basis in the EPC. However, that is a matter of treaty interpretation, which requires, under the VCLT, a combination of the grammatical, systematic, teleological and historical interpretation methods, with no fixed hierarchy between them. For the teleological and systematic analysis, the legitimate interests of applicants and the Office (resp. public at large) must be considered. The original post only asserted applicants’ interest in low costs – as such an entirely legitimate concern – (leaving aside the point of the job fun of patent attorneys) but did not articulate why the *description* amendments are expensive to make and did not address the case of *description* amendments made for you by the Examiner.

It would be helpful if the proponents of abolishing the current requirement to adapt the description would identify a legitimate interest of applicants for keeping the description inconsistent with the claims (which they amended themselves in the first place). Such a legitimate interest could be ‘low costs’ if it would be clear why adding ‘not according to the claims’ a few times must be so expensive (relative to the total procedure), as asserted in the original post. We could then consider such a legitimate interest in low costs under the teleological interpretation of the relevant EPC provisions – the purpose of the EPC is not to make the grant procedure unnecessarily expensive and complicated.

The legitimate interests of the general public in having a consistent description in the B1 publication are, of course, avoiding Angora cat tactics of proprietors, i.e. reducing the wiggle room for proprietors in litigation. So, we must balance this legitimate interest of the general public against some possible legitimate interests of the applicants (and combine the result of that balancing with the results of the other treaty interpretation methods).

Concerned Observer asserts a risk under Art. 123(2) (“thus invariably creates a risk of added matter”). Avoiding this risk for applicants could be a legitimate interest of applicants. However, Concerned Observer does not spell out precisely what the risk is. Prima facie, the phrase ‘not according to the claims’ does not present technical information.

Indeed, you ask for examples. I’ve studied the Ensygnia v Shell case and would not dismiss it solely for relating to a national patent. However, I find the case very unclear and understand the issue was about post-grant amendments of the claims (para. 164 and para. 191; 201 “now falls within the scope of * the claim as amended post grant* “).

Concerned Observer also refers to the case law about undisclosed disclaimers, but the relevance of G2/03 is unclear to me.

To be clear: I would welcome Concerned Observer and other proponents of abolishing the requirement to (further) clarify the risks under Article 123(2) and (3), e.g. with real or hypothetical examples.

The original authors wrote, “We see no compelling reason why the description should not be allowed to include more support than specifically needed for the claim”. I think the burden of persuasion is on the proponents to identify a compelling reason for changing the established practice of the EPO, not the other way around (at least in practical terms of persuading the relevant people at the EPO).

Wiggleroom, if one interprets the claims in the light of the description, then anything in the description labelled as “not the invention according to the claims” becomes relevant to the interpretation of the claims.

Stating what the invention is NOT can help to define what the invention IS. Therefore, at least with respect to proceedings before the national courts and the UPC, it is NOT correct to claim that “the phrase ‘not according to the claims’ does not present technical information”.

With this in mind, it does not take much imagination to realise why the scope of the claims would be changed by the (incorrect) application of a label to an embodiment which would otherwise fall within the claims. For example, the incorrect labelling of an embodiment as “not according to the claims” might (e.g. by forcing an unusual definition of certain terms) cause the claims to be interpreted as relating to subject matter not clearly and unambiguously disclosed by the application as originally filed. That would add new matter. Removing the (incorrectly applied) label after grant might extend protection. Hence a potentially inescapable trap.

Does that help to clarify the matter for you?

I think we are getting to a point – with quite some development from the original blog post’s argument about adding the phrase “not according to the claims” being time-consuming and tedious.

I think that concrete examples—hypothetical or from real cases—where the applicant is treated harshly by the current practice of the EPO in combination with an Art.123(2)/(3) trap could be more persuasive in making your case.

What really bothers me in this mess is that – as @DXThomas and the authors of this post rightly pointed out – the BA in T 56/21 did not follow through with a referral to the EBA. The decision T 56/21 contains no fewer than 118 occurrences of the phrase “Article 69”, yet the function of Article 69 EPC is the entire point of the referral in G 1/24.

This whole adaptation of the description is a bit ridiculous for us attorneys, considering that we are constantly told by EPO examiners that only the claims are to be taken into account for determining the scope of protection, i.e. one of the two …

Mr Thomas, I think that you are missing the point.

Are you claiming that it is literally impossible for a national court to rule that new matter is added by the incorrect labelling of an embodiment as “not according to the claims”?

The point of referencing Ensygnia v Shell is that it illustrates how, in proceedings before national courts, amendments to the description can change the extent of protection conferred by the claims. The rest of my comment merely spells out some of the logical consequences / implications of that fact.

You may not wish to acknowledge that the EPO’s “strict” description adaptation practice gives rise to potentially very serious risks for applicants. However, one need only make logical deductions from known facts to see how those risks can arise in practice. Like it or not, those risks are therefore real.

From the perspective of many patent owners, modifying the description at the prosecution stage to an examiner’s view of the claims is premature and an unnecessary expense. The description should be what it was at the time of filing, subject only to possible deletion of unclaimed examples. The vast majority of EPs will never be litigated. When litigation occurs, the claims can be interpreted in light of the issues and amended if necessary, without addressing many needless hypotheticals.

@Thorsten

Your remarks are well taken.

As to the adaptation of the description, very recent developments seem to signal a change of tack at the EPO.

First, the 2024 version of Guideline F-IV 4.13 has been amended to state that the description must be adapted to the claims when inconsistencies cast (present tense) doubt about the meaning of the claims, instead of « could cast doubt » in the previous version. This aligns the requirement of the GL with the language of PCT Rule 5.29. This amendment is significant and quite positive for practitioners since the requirement to remove an inconsistency is now subject to a showing by the examining divisions that it makes the claim unclear. It is also a marked improvement in terms of harmonisation when the EPO rule becomes the same as the PCT rule.

It is surprising though that the list of updates of the 2024 Guidelines published by the EPO depicts this amendment as « minor » and does not detail its content.

Second, possibly as a result of this amendment and of internal instructions, a radical change seems to have occurred since April or May 2024 in the practice of examining divisions as to amendments entered at the Rule 71(3) stage. There are no longer substantial and numerous amendments. It is to be confirmed that this true in all technical fields and for all examining divisions.

Third, the SQAP 2023 report published by the EPO in June as an annex to the quality report highlights the critical comments of practitioners as to the requirement to adapt the description.

A workshop on clarity is organised by the EPO on 20 & 21 November as a session of the SACEPO Working Party on Quality Group. This may give the EPO an opportunity to clarify its stance.

Wiggleroom, if you are looking for a suitable (hypothetical) illustration, how about the patent underlying the referral in G 1/24?

Interpreted in the light of para [0035] of the description, a “gathered sheet” would be understood as:

“convoluted, folded, or otherwise compressed or constricted substantially transversely to the cylindrical axis of the rod”

On the other hand, interpreted in isolation (but in accordance with the allegedly clear and widely agreed meaning in the tobacco industry), the term “gathered sheet” would instead be understood as:

“folded and convoluted to occupy a tri-dimensional space”

Now imagine that, before grant, para [0035] of the description had been amended to match the latter (standard) definition.

Can you see the definition in AMENDED para [0035] as being directly and unambiguously derivable from the disclosures of the application as originally filed?

Also, what meaning is a national court supposed to afford to the term “gathered sheet”? The court would of course consult the description and drawings. Does this therefore mean that they would afford “gathered sheet” the meaning set out in AMENDED para [0035]?

And what then would happen if, quite reasonably, the opposite party in national proceedings pointed out that the amendments to para [0035] introduce new matter?

The problem here is that, whilst the EPO interprets claims in isolation, the national courts do not. Instead, the national courts often take a great deal of time and effort to consider various sources of intrinsic and extrinsic evidence (eg expert opinions / declarations) to determine the correct meaning of the terms used in the claims. It is therefore a near certainty that, by using such a vastly different approach, the national courts will – even for the assessment of validity alone – arrive at interpretations of the claims that differ in one way or another from the interpretation adopted (either explicitly or implicitly) by the EPO.

Can you now see the problem with applicants being forced to amend the description in accordance with the (different) claim interpretation approach adopted by the EPO?

Wiggleroom, I should add that the above, “gathered sheet” example merely illustrates one way in which post-grant claim scope can be affected (AND new matter added) by adapting the description to the subject matter of the claims as interpreted by the EPO.

However, discrepancies between pre- and post-grant claim interpretation approaches are not the only way in which this can happen. Another way would be that previously discussed, namely incorrect labelling of an embodiment as “not according to the claims”.

Consider a hypothetical example of the “gathered sheet” patent which describes an embodiment of the invention of the application as originally filed. Imagine then that said example:

– illustrates one way in which a sheet of tobacco can be “folded and convoluted to occupy a tri-dimensional space”; but

– before grant, is INCORRECTLY labelled as “not the invention according to the claims”.

How would the claims then be interpreted after grant? Would the national court need to interpret “gathered sheet” in such a way that it covers ALL ways in which a sheet of tobacco can be “folded and convoluted to occupy a tri-dimensional space” EXCEPT that illustrated in the example labelled as “not the invention”?

If so, how could such an interpretation possibly be derived (clearly and unambiguously) from the disclosures of the original application?

The point here is that claim interpretation can be a VERY tricky process. There may be a LOT of information to weigh and balance, especially if one is trying to anticipate how a national court might interpret the claims. Mistakes are to be expected, especially as it sometimes takes a lot of time and thought to figure out that what appeared at first sight to be a clear term in a claim turns out to be nothing of the sort. Frankly, in most cases, neither examiners nor patent attorneys have the time and the resources to complete a comprehensive claim interpretation analysis.

We can therefore conclude that claim interpretations used during proceedings before the EPO are somewhat “rough and ready”. If we then take into account the possibility of human error with labelling embodiments as “not according to the claims”, we can most definitely conclude that the EPO’s “strict” description adaptation practice ALWAYS comes with legal risks for applicants … including fatal risks stemming from even the most innocuous looking of mistakes, misunderstandings or misinterpretations.

From a practitioners view, adapting the description, at least in the biotechnological field, can be a truly challenging, time intensive and difficult manner. IN almost all of the cases, the description will provide a more general outline that orientates the reader. Of course this outline is more general than the main claim. Then, we often have the situation that some terms have been clarified in the claims and that several restrictions have been made to the claims. Regularly, a unity objection has separated a more generically defined embodiment into several more specific inventions. It can easily mean 2000-3000 EUR of extra expenses for the applicant. If at least it were all good with that, but it isn’t.

It’s a risky endeavor for two reasons:

1) An embodiment falsely declared as “not according to the invention” might lead to a loss of protection in litigation, because the court will have to assume that the embodiment was deliberately excluded.

2) Leaving an aspect un-adapted may lead to an interpretation of a national court that a claim is not properly supported by the description (be it by way of lack of enablement, lack of written description or the lack of literal support in the adapted description is taken as an indication that the claim may represent added matter). Further, the EPO may not grant the patent if it deems the (alleged) discrepancy between claims and description unresolved.

Essentially, in proceedings before the EPO the outcome with respect to Article 84 EPC can only have two states: (i) the claims comply with Article 84 EPC, (ii) the claims do NOT comply with Article 84 EPC. An EP patent will only be granted when state (i) applies.

State (i) can be achieved by (a) amending the claims (about 97% of the cases) or by (b) amending the description (about 3% of the cases; repairing/restricting overly broad definition of terms).

For (a), if the claims as such are clear, where is the need to consult or adapt the description? Again for (a) if the claims are clear in view of the application as filed (definitions), where is the need to (further) revise the specification?

For (b), if the specification (definitions) has already been amended to achieve status (i), where s the need to further revise the specification?

So what exactly are we talking about? We are talking about those cases where a legal entity, which is NOT the EPO, requires further guidance/interpretation. This need for further guidance/interpretation may be due to completely different aspect as compared to the grant proceedings before the EPO. Yet it is the EPO that imposes an adaptation to the description? It is questionable that mirroring the amendments made to the claims onto the description will predictably help that legal entity.

Removing clear (!) discrepancies between about-to-be-granted claims and the description, omitting clear (!) a priori non-unitary inventions is easy, fast and desirable (and I advertise doing the latter to save translation costs).

The current implementation at the EPO, where a broader definition/description is regarded as incompatible with the narrower claims, requiring amending the entire description like it was an enormous claim set is difficult, error-prone, expensive, risky and possibly or even likely not even helpful for later interpretation in my view.