My British colleague has already commented brilliantly on the UK ruling in this case from the point of view of plausibility (see here). For my part, I’d like to comment the French ruling in the same case, which takes the opposite view to the UK decision. We shall see that the French position is particularly pro-patent, more especially through the interpretation of the plausibility notion and of the priority right.

The facts

Patent EP1427415 (“EP’415″) was filed in the name of Bristol-Myers Squibb Company (“BMS Company”) on September 17, 2002 in the form of international application PCT/US02/29491 (WO 03/026652) (“WO’652”), under the priority of provisional application US 60/324,165 of September 21, 2001. It expired on September 17, 2022 and forms the basis of SPC FR11C0042, which will expire on May 20, 2026.

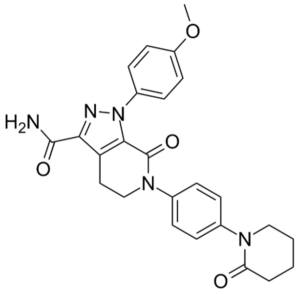

EP’415 claims apixaban (claims 1 and 2), the pharmaceutical composition comprising it (claims 3 and 4), the compound and the pharmaceutical composition for use in therapy, in particular to treat thromboembolic disorders (claims 5 to 22), optionally in association with a second therapeutic agent to treat thrombolytic disorders (claims 23 to 29).

Apixaban (1-(4-methoxyphenyl)-7-oxo-6-[4-(2-oxopiperidin-1-yl)phenyl]-4,5,6,7-tetrahydro-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-c]pyridin-3-carbamide)

The patent is unopposed. However, several invalidity proceedings have been initiated worldwide. For example, the validity of the Canadian patent (CA2461202) has been challenged on several grounds, but without success (Federal Court judgment of January 12, 2021, in BMS v. Pharmascience & Sandoz). In addition, Sandoz and Teva applied for a declaration of invalidity of the UK part of the application on the grounds of lack of inventive step, in particular in view of the international publication WO 00/39131, lack of plausibility and extension beyond the content of the application as filed. The plaintiff obtained the revocation of the patent, Judge Arnold having found that, in the absence of any theory based on the structure of apixaban or of any data appearing in the description, by way of example, nothing in the application supports the assertion that apixaban is a factor Xa inhibitor. As such, the assertion is not plausible, because the application gives the skilled team no reason to believe that there is a reasonable prospect that the assertion will turn out to be true.

The content of the French decision

Unlike the British judge, the Paris Court decided that the claim that apixaban is a factor Xa inhibitor was plausible in the frame of inventive step assessment.

In the present case, the initial application contained neither paragraph [00028] nor paragraph [00180], cited above, which were added during the examination phase in 2008, i.e., well after the priority date; similarly, the claims were completely recast: they initially claimed protection for a very large number of compounds (74) based on the possible variants of the various substituents around the central structure. It could be deduced from this that the applicant was not in possession of the invention at the time of filing, and that it filed on the basis of an idea or an intuition. The Court notes, however, that the initial WO’652 filing specifically discloses apixaban, which is further exemplified (no. 18), admittedly among 140 examples and the description of more than 100 product syntheses. This being the case, the court notes that this WO’652 document reveals tests, resulting in the determination of “most preferred” compounds with very good affinity and in particular a Ki # 0.001 μM. WO’652 further states that the invention relates to a factor Xa inhibitor with improved pharmacological and pharmacokinetic properties. It also describes that 3.07 g of apixaban have been synthesized (page 178). This quantity unquestionably distinguishes apixaban from all other examples of synthesized compounds, in that it is by far the largest quantity synthesized according to the description (no other example reaches one gram, the other largest quantity synthesized being example 91: 0.34 g). A person skilled in the art would necessarily have deduced, on the basis of common general knowledge, that the patentee thought apixaban was a promising compound, if not the most promising.

In addition, BMS has submitted laboratory notebooks and reports from its researchers, prior to the filing of the WO’652 application, which demonstrate indisputably, and moreover not seriously disputed, that it was in possession of the invention, i.e., a factor Xa inhibitor, useful in the treatment of thromboembolic disorders, with improved pharmacological and pharmacokinetic properties. These elements fully confirm the research program as outlined by BMS, and the discovery of apixaban by Dr. Pinto and his colleagues before the priority date.

The Court deduced that the plea alleging the lack of “plausibility” or “credibility” of EP’415’s contribution to the state of the art at the time of filing, and hence the lack of inventive step of claims 1 to 4, was therefore rejected.

Furthermore, with regard to the priority right, the Court points out that the assignment of the priority right stemming from provisional application US 60/324,165, which was an asset of BMS Pharma (and not of BMS Company which filed WO’652), should in principle have been made in writing between November 3, 2001 (the date on which the inventors assigned their invention to BMS Pharma) and September 17, 2002, date of filing of the PCT application, to BMS Company, for the latter (BMS Company) to be considered the successor in title of the former (BMS Pharma) within the meaning of the Paris Convention, so that the latter could be considered to have validly exercised the priority right.

However, the French Judge refers to a statement made by Judge Holland, which nuances this “binary” conclusion on the strict distinction between companies, stating that in certain hypotheses, the law of the State of Delaware (in which both BMS Pharma and BMS Company are incorporated) allows “the corporate veil to be lifted”, which results from an attestation, and is confirmed by Judge Chandler’s testimony. In this case, BMS Pharma was a wholly owned subsidiary of BMS Company, so the management of the patent portfolio was entirely decided by BMS Company in its sole interest, with the result that the Court ruled that the priority right had been assigned without a written document.

The scope of the French decision

In my view, two aspects of judgment are particularly interesting: plausibility and priority.

French case law contains numerous examples of the application of the notion of plausibility. For example, it has already been ruled that an invention must have a “credible” or “plausible” technical effect at the date of filing, and its absence is sanctioned on the grounds of lack of inventive step (e.g., TGI Paris, October 6, 2009, RG n°07/16446, Teva v. Sepracor). Or that the credibility of the technical effect is assessed at the priority or filing date (e.g., TGI Paris, October 6, 2009, RG n°07/16446, Teva v. Sepracor), in the light of the elements contained in the application, including the patentee’s assertions, without the latter being obliged to provide in the application the results of tests or trials or any other data (e.g., CA Paris, October 29, 2020, RG n°126/2019, Ethypharm v. Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp). Post-filing elements may also be taken into consideration but cannot serve as the sole basis for demonstrating the credibility of the technical effect (e.g., TGI Paris, October 6, 2009, RG n°07/16446, Teva v. Sepracor).

The decision clarifies that a technical effect may be plausible without requiring the provision of tests or data; this is precisely the opposite of what was decided by Judge Arnold in the United Kingdom. But this flexibility is in line with decision G 2/21 of the EPO’s Enlarged Board of Appeal: it seems to be a recognition of ab initio implausibility, i.e., that evidence subsequent to the filing date can only be disregarded if the person skilled in the art had legitimate reasons to doubt that the technical effect could be obtained at the filing date (e.g., T919/15, T578/06, T2015/20). The court further specifies that the patentee is expected to describe the claimed new effect by means of tests, in particular, so that the person skilled in the art understands the invention and it is considered “plausible” (and sufficiently described), but only if the patent relates to a subsequent therapeutic application of a substance or composition (e.g., Cass. Com., December 6, 2017, n° 15-19.726).

With regard to the assignment of priority rights, according to case law, assignment of the initial application does not automatically entail assignment of the priority right. According to the French Supreme Court, the priority right constitutes “a right distinct and independent from that conferred by the first patent application“. As such, the assignment of this right requires the inclusion of an express clause in the patent assignment contract and cannot result from the simple mention “with all the rights attached thereto without any reservation or exception“. The position adopted on this point by the Paris court, while somewhat overshadowed by the contribution on plausibility, is nonetheless important and in contradiction with previous case law.

A few comments

Firstly, with regard to plausibility, in the present case, it should be remembered that international application WO 00/39131 concerned compounds structurally close to apixaban (see for example compounds 1041 to 1053 on page 240 applied to the first general formula in Table I on page 207 when G = 4-(methoxy)phenyl) presented as factor Xa inhibitors useful for the treatment of thromboembolic disorders. This application therefore constitutes the closest state of the art suitable for the application of the problem-solution approach. No particular technical effects were associated with the structural difference between apixaban, and the compounds described in WO 00/39131. The objective technical problem could therefore be formulated as finding a useful factor Xa inhibitor for the treatment of thromboembolic disorders, as an alternative to those described in the international application WO 00/39131. No experimental data had been presented in the patent showing that the compounds in question, and apixaban in particular, would have an effect underlying a therapeutic effect.

By recognizing plausibility in this case, the Court of First Instance adopts a flexible interpretation of plausibility. While it is thus in line with the EPO’s G 2/21 decision, by adopting the more favorable position of ab initio implausibility, it nevertheless gives an interpretation opposed to that of the English judge. While the latter considers that tests and data are compulsory, the French judge considers, conversely, that they are not compulsory, except in the specific case of subsequent therapeutic application.

This position thus tends to set the threshold of plausibility at a particularly low level, which is undoubtedly favorable to the patentee. In itself, this reading is not shocking in that it is part of a general trend. But just because a decision is part of a general trend doesn’t mean it should be approved. In this case, it seems to me that the use of plausibility is intended to facilitate the assessment of patentability in a field marked by the randomness of the results achieved by claimed inventions: the pharmaceutical field. However, we must remain cautious about lowering the assessment of this criterion, which is already intrinsically favorable to applicants, too far. To do otherwise would be to give an undue advantage to an applicant who could reserve for himself the exploitation of an invention that tends to fall more within the domain of research than that of technology. So, to sum up, plausibility will only be ruled out if the person skilled in the art had legitimate reasons for doubt at the time of filing, so that the applicants can claim an entire field of research for themselves, without having yet begun to work on it.

It should also be noted that the Court confuses technical contribution, concrete result and technical result. The technical contribution does not lie in a technical effect, but in the invention’s contribution to the state of the art. The technical result can be distinguished from the concrete result, although I personally doubt this very seriously, but it would still be necessary to specify in this case what characterizes the technical result, which the Court did not do in this case.

As far as the priority right is concerned, I remain more astonished and critical. Here again, the position adopted is (very) favorable to the patentee, and in particular to American patentees, who are experiencing numerous difficulties linked to the absence of assignment of the priority right. The pragmatic interpretation adopted, which is based on the theory of appearance (i.e., the subsidiary behaves like the patent owner) is interesting, but it is the result of numerous confusions designed to conceal the fact that the priority right has simply not been properly assigned. In fact, taking over patents does not necessarily imply taking over priority rights, since these can be assigned independently. And the fact that a company belongs to a group does not mean that all its assets have to be transferred to its parent company. Finally, last but not least, when a chain of rights is broken from the outset, as is the case here, since the priority right has never been assigned, I find it hard to see how any subsequent acts could remedy the situation. Finally, while I can easily understand the theory of appearance (i.e., behaving like an owner towards others gives me the appearance of the owner of the property right), I have more difficulty conceiving that the subsidiary, which is a separate company to which no rights have been assigned, can also, like the mother, benefit from this theory. Unfortunately, this does not encourage patentees to properly formalize their assignments of priority rights, which cannot be approved if we look at the patent system as a whole. Formalism is not (only) there to annoy the users of this system, but also to ensure that it functions correctly and can, in this case, clearly indicate who the right holder is.

In conclusion, there can be little doubt that this decision is favorable to patentees, that at the dawn of the UPC, French judges are reminding us that they will still, and perhaps more than ever, have their say, and that this trend, which has been underway for several years in France, is not likely to die out any time soon, because the Cour de Cassation will be welcoming the most eminent patent law specialist from the Paris Tribunal Judiciaire to its midst this autumn.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Patent Blog, please subscribe here.

Do you have a link or a reference to the French ruling?

Really, the most revealing information emerging from this case is the following:

“In addition, BMS has submitted laboratory notebooks and reports from its researchers, prior to the filing of the WO’652 application, which demonstrate indisputably, and moreover not seriously disputed, that it was in possession of the invention, i.e., a factor Xa inhibitor, useful in the treatment of thromboembolic disorders, with improved pharmacological and pharmacokinetic properties.”

This means that, at the filing date of WO’652, BMS was in possession of data relating to apixaban that would have rendered “plausibility” (and with it any doubts regarding inventive step) a complete non-issue.

For some reason, BMS decided not to include those data in WO’652. This has undoubtedly proven to be a costly decision. It is also a decision that is hard to understand, given the presence of other clear pointers in WO’652 (including a multi-gram preparative method) to apixaban being the most preferred compound.

Of course, we now have the benefit of hindsight, and so should be careful not to be too harsh in judging the situation. Still, this serves as an object lesson in what can happen if one approaches the patent bargain with an strategy of revealing as few details as possible about one’s invention.