On 21 March 2023, Meade J gave a bumper judgment in the revocation action brought by Gilead in respect of two of NuCana’s patents from the same family (EP (UK) 2 955 190 and EP (UK) 3 904 365, the “Patents”), which relate to nucleoside analogues. Filling 102 pages, the judgment raises a number of topical procedural and legal issues, from added matter, plausibility standards and the (then pending) decision of the Enlarged Board of Appeal in G2/21, to co-pending EPO opposition proceedings and appeals, instruction of experts and more. Especially when combined with the lengthy G2/21 decision, it makes for a serious read!

Technical background

Nucleoside analogues (“NAs”) mimic nucleosides, the building blocks of DNA and RNA, but are modified such that they interfere with cell replication via a range of routes, which causes them to inhibit cell growth or trigger cell death (apoptosis). Such cytostatic or cytotoxic effects formed the rationale for the utility of NAs as antivirals and anti-cancer drugs.

By the priority date, a known difficulty with achieving a therapeutic effect with NAs is that (like natural nucleosides) they are not hydrophobic and therefore cannot enter a cell passively; they must be carried across the cell membrane via transporters. These transporters are susceptible to building resistance, as they may become downregulated.

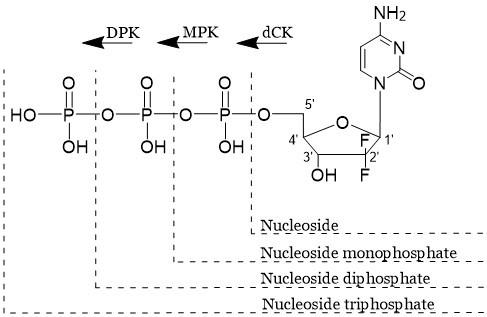

Once inside a cell, NAs are triphosphorylated into their active form in three steps, illustrated in the diagram below, which is taken from the parties’ Statement of Agreed Common General Knowledge annexed to the judgment:

The first phosphorylation step was known to be rate limiting and there was an interest at the priority date in developing monophosphorylated NAs, but monophosphorylated NAs are charged and cannot enter a cell. Hence, protecting groups had been used to mask the negative charge and improve cellular uptake.

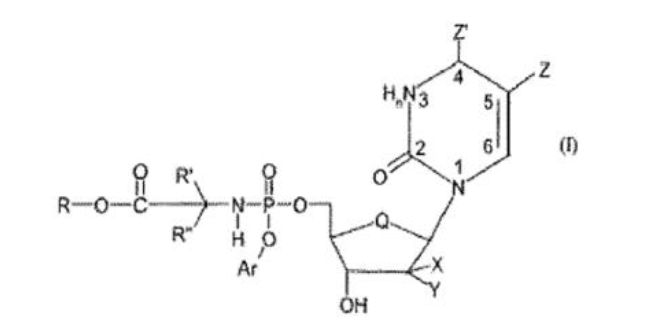

A common general knowledge NA with anti-cancer activity at the priority date was gemcitabine. The compounds claimed in the Patents include the nucleoside moiety of gemcitabine, or similar, claimed by the following Markush formula (Formula I):

The claims then included lists of possible moieties for each of the substituent groups in the Markush formula.

Added matter

NuCana had applied unconditionally to amend claim 1 of EP 190 to delete some of the possible substituent groups included in the Markush formula. Claims 1 and 2 of EP 365 had been narrowed in prosecution. Gilead argued that the resulting Patents added matter as the statements of utility in the Patents would apply to a different narrower class of compound not taught in the original application.

The judge reviewed the national case law on selections/deletions from multiple lists (Merck v Shionogi [2016] EWHC 2989 (Pat), Nokia v IPCom [2012] EWCA Civ 567 and GlaxoSmithKline v Wyeth [2016] EWHC 1045 (Pat)) and the EPO cases reviewed therein and in the EPO Case Law Book. As well as setting out the basic approach to be applied, the judge distilled and set out the reasons for the rule against adding matter. In particular, the judge noted that it could circumvent the first-to-file rule if an applicant were permitted to freely narrow down a Markush formula, as the applicant could rely on the original application’s filing date in respect of an invention that was not in fact disclosed (and therefore the amendments might constitute a selection-type invention which had not in fact been made at the filing date).

In the present case, the selections amounted to more than a mere reduction and it was not right that there was adequate disclosure of any possibility in each list. The narrowed lists also did not correspond to preferred options.

Of particular interest were the judge’s comments on the relevance of whether the selection generates another invention and the motive for introducing amendments. The judge considered it relevant that the selections defined a new class that did not cover (i) inactive compounds or (ii) those that could not be made, and avoided an obviousness attack. This was not essential to the conclusion of added matter but reinforced it (he saw these points as all being symptoms of there being a different invention put forward in the amended patent). He also noted that while the effect of the amendment, such as to allow a new argument on inventive step, may also be relevant to added matter, that is not the same as the motive for introducing an amendment. As the judge summarised: if there is basis for an amendment, it will not be refused because the patentee wants to solve an insufficiency problem, and if there is no basis for the amendment then it will not be allowed whatever the motive.

Industrial application and plausibility

As readers will be aware, the general principles for assessing industrial applicability are: the patent must disclose a practical application for the claimed product or process, a concrete benefit from the use in industrial practice must be derivable from the description when read with the common general knowledge, and a merely speculative use will not suffice (see HGS v Lilly [2011] UKSC 51).

There was dispute between the parties as to what amounts to a “practical application”, although ultimately, industrial application did not require separate consideration from the arguments on plausibility. Essentially, Gilead’s attack on industrial application was deployed so that it could argue, if necessary, that if the Patents rendered some degree of cytotoxicity plausible it had no practical utility.

So moving to plausibility, the present plausibility test set by the UK Supreme Court in Warner-Lambert is whether the patent contains “something that would cause the skilled person to think that there was a reasonable prospect that the assertion would prove to be true”. Given the impending (now issued) decision of the EBA in G2/21 the judge acknowledged the possibility of national law adopting in the future either the ab initio plausibility or ab initio implausibility standard and assessed plausibility under both tests.

NuCana argued that the technical contribution of the Patents was a class of compounds of Formula I plausibly having the potential to be used in the treatment of cancer. This was rejected as amounting to an argument that “the specification just has to render it plausible that the effect might or might not exist, which is meaningless.”

NuCana’s second argument was that, rather than themselves being useful to do something, study of the class of compounds of Formula I would be useful to understand mechanisms of action and structure-activity relationships. The judge also rejected this; there was no support in the Patent for the compounds’ utility as a research tool and the case law is explicit that there has to be some practical utility of the invention.

Plausibility was therefore assessed on the alleged technical contribution that the Patents disclosed a new class of phosphoramidate nucleoside analogues with cytotoxic activity. NuCana also relied on improved intracellular delivery although not as a standalone contribution, this being argued to bolster the alleged cytotoxic activity technical contribution, and vice versa.

On the evidence, the judge found that a skilled person would consider that a significant number of compounds falling within the claims of the Patents would have cytotoxic activity but that a significant number would not. Apart from the three compounds for which experimental data was present in the Patents, the skilled person would be completely unable to predict which compounds fall within which category based on the teaching in the specification. There was no information regarding the mechanism of action of the compounds and it was a matter of CGK that small changes in structure can make a big difference to activity, including removing it all together. This lead to the conclusion that the alleged invention was not rendered plausible across the claim scope under ab initio plausibility or ab initio implausibility (so it did not matter that this judgment was handed down just days before the G2/21 EBA decision).

Sufficiency / “existence in fact”

This was an argument about whether the compounds within the claim do in fact have the level of cytotoxicity called for (as opposed to whether such activity was plausible). The relevant cut-off level for cytotoxicity was taken to be that asserted by NuCana, 100 uM. Assay results from the Patents, for sofosbuvir, from scientific papers and the parties’ disclosure were summarised in Annex B to the judgment. The judge accepted that based on this data, Gilead had shown on the balance of probabilities that a significant number of compounds covered by Formula I did not have measurable cytotoxicity and therefore the claims of the Patent were insufficient.

Undue burden

The judge noted that the hearing was essentially two trials in one, due to the separate issues that arose in relation to Gilead’s undue burden insufficiency arguments. There were even separate barrister teams dealing with this issue. However, having fought essentially the same undue burden issues before in Idenix v Gilead [2014] EWHC 3916 (Pat), it is unlikely Gilead felt they got two trials for the price of one!

The evidence submitted was extensive and comprised evidence from the experts, litigation experiments and factual evidence recording work done in synthesising relevant compounds around the priority date. In relation to Idenix, although the judge was familiar with the judgment he acknowledged he had avoided analysing the factual details, as his task, as was agreed by the parties, was to analyse the issues on the evidence before him.

The relevant issue was whether it would involve undue burden for the skilled team to make a category of compounds which, it was accepted, constituted a significant (and not de minimis or irrelevant) part of the claims. These were termed “2MU2FD” compounds (i.e. where X is methyl and Y is fluorine and the former is orientated up and the latter down). The judgment highlights three points of importance. First, the test is not whether the synthesis was impossible (clearly sofosbuvir has been made) but whether it involved undue burden. Second, a patent can be sufficient on the basis of CGK alone. Third, the primary evidence is that of the expert witnesses, with the task of putting themselves in the shoes of the skilled person; this evidence should not be lost sight of in light of the volumes of secondary evidence presented in the case.

Relevant to whether the synthesis of the 2MU2FD compounds involved undue burden was that:

- It involved a risk of an unfamiliar fluorination step that required information outside the skilled team’s CGK for success

- There were a number of parameters in an experiment that would need to be adjusted

- The primary and secondary evidence showed the influence of personal choice on the synthetic route taken and therefore likelihood of success

- The difficulty in choosing between potential routes showed that the problem was complex and gave rise to serious and unpredictable potential problems

These factors all supported the judge’s finding that producing the 2MU2FD compounds involved undue burden. The judge reflected on the experts’ approach to the hypothetical task and found that Gilead’s expert witness had adopted an approach reflective of the skilled person, with an appreciation of these factors. On the other hand, NuCana’s expert had identified routes he personally thought might work, in light of his considerable experience. Further, the manner in which he was first instructed for EPO proceedings was likely to have influenced his approach.

Infringement

By the end of trial Gilead accepted that the Patents covered the active pharmaceutical ingredient sofosbuvir, which is contained in Gilead’s Sovaldi, Harvoni, Vosevi and Epclusa anti-viral products. Infringement was therefore no longer in issue. However, it could have been an interesting argument as the judgment notes that it had appeared Gilead might seek to argue that the claims (all compound claims defined by Markush groups) were implicitly limited to use in cancer, this being the technical effect disclosed (if any). In opening submissions, Gilead accepted that the claims were to be construed as being to the products per se on the basis of Fibrogen v Akebia [2021] EWCA Civ 1279, so this point was not considered.

Practice points

In terms of practice points, Meade J reiterated the importance of the parties keeping the Court informed of developments at the EPO. A TBA hearing in the opposition proceedings for EP 190 was scheduled to take place shortly after the judgment being handed down. As it was, the judge concluded that it was better to write his judgment while the issues were fresh than wait for a decision, particularly in view of the additional delay in waiting for the EPO to publish the reasoned decision of the TBA. However, the judge noted it would have been desirable for the Court to be able to make an informed choice.

The judge also commented on the instruction of experts where they are initially engaged to assist at the EPO. In such circumstances, record keeping regarding the manner in which they are instructed is particularly important. Here, one of NuCana’s expert witnesses had assisted with the EPO proceedings, where he had essentially been tasked with considering counter-arguments to Gilead’s statement of opposition. The judge found that this meant that the expert had been tainted by hindsight and was unable to properly put himself into the position of the skilled person with their common general knowledge. This limited the reliance placed on his evidence. Many readers will be aware of the significant time and expense involved in the instruction of experts if the sequential unmasking process is followed in relation to the prior art. They will also be aware that it is not uncommon for parties to start working with an expert for EPO proceedings long before UK proceedings are even in contemplation and therefore before UK lawyers are involved, or in circumstances where it would be disproportionate to go through the UK process “just in case” the expert may be needed in the future. Whilst there has in the past been judicial acceptance that the sequential unmasking is sometimes not practical, it is clear that the need to do as much as possible to avoid hindsight in the views of the experts used in the UK is here to stay.

A copy of the judgment can be found [here]

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Patent Blog, please subscribe here.