The concept of plausibility has caused great controversy in European patent law in recent years. It was hoped that the decision of the Enlarged Board of Appeal (EBA) of the EPO in G 2/21 would bring clarity. Since the referral questions by Board 3.3.02 were very clear and seemed to present reasonable alternatives from which the Enlarged Board could have selected one, this hope appeared justified. However, following the Enlarged Board’s answer in G 2/21, many questions remain.

Plausibility in IP – A Brief History in pictures

It goes without saying that the term plausibility appears nowhere in the EPC and is no requirement of patentability, in contrast to novelty, inventive step and industrial applicability. Nonetheless, plausibility entered the realms of IP Law around the year 2005, when Technical Board of Appeal 3.3.08 came up with the following famous catchword:

The definition of an invention as being a contribution to the art, i.e. as solving a technical problem and not merely putting forward one, requires that it is at least made plausible by the disclosure in the application that its teaching solves indeed the problem it purports to solve. Therefore, even if supplementary post-published evidence may in the proper circumstances also be taken into consideration it may not serve as the sole basis to establish that the application solves indeed the problem it purports to solve.

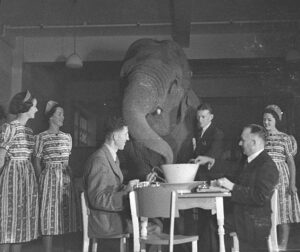

Fig. 1: Plausibility enters the realms of Intellectual Property Law

(all pictures taken from commons.wikimedia.org)

Since the Board in T 1329/04 explained in quite some detail and with a scientific foundation why it considered the invention covered by claim 1 as too broad and speculative, this result of this decision did not raise a lot of controversies as such. Nonetheless, it of course opened the door for examiners and opponents to argue that an invention may not solely rely on post-published evidence for the effects asserted to be associated with the claimed subject-matter, absent a plausible showing that the teaching of the invention indeed solves the problem it purports to solve.

However, it did not take very long until this catchword was applied to other and in fact much more narrowly defined inventions, and even to claims covering only a single substance. Perhaps the most famous (or infamous) of these cases is the Dasatinib decision T 488/16, where a patent directed to a single (blockbuster) substance, i.e. dasatinib, was found to lack an inventive step, most likely because this substance had been buried/hidden in a plethora of other substances with very little concrete data and many possible mechanisms of action, i.e. many targets which dasatinib might bind to. Under these circumstances, TBA 3.3.01 held that the applicant was not allowed to rely on post-published evidence, even though the effect that dasatinib had was, among others, generically disclosed in the application as filed. A statement that “compounds have been tested in these assays and have shown activity” was considered too meagre by the Board to allow such reliance on post-published evidence. The elephant was now firmly settled in the China shop.

Fig. 2: Plausibility in EPO Dasatinib Decision T 488/16

The EPO’s Case Law on plausibility then spilled over to the United Kingdom and developed a life of its own. The most famous decision might be the UK Supreme Court’s Ruling in Warner-Lambert Company LLC v Generics (UK) Ltd, which was reported on this blog here. This decision saw “their Lordships split in opinion“, with the majority voting that “the specification must disclose some reason for supposing that the implied assertion of efficacy in the claim is true“. Plausibility was held as being just an aspect of the underlying principle of sufficiency. A roaring success for the concept of plausibility, which was thereby elevated to an aspect of a ground for revocation by itself.

Fig. 3: Plausibility reaches the UK Supreme Court in Warner-Lambert Company LLC v Generics (UK) Ltd

While Warner Lambert was a decision made in the context of a second medical use claim, this Case Law was soon also applied to product claims in the UK. If and when the activity of substantially all of the claimed substances is not plausibly shown in the application or was at least clear to a skilled person from their common general knowledge, then such claims will be found to lack plausibility, which in the UK will then result in their revocation for lack of industrial applicability without further ado. This is what recently happened, inter alia, in Gilead vs. NuCana 2023 EWHC 611. Good bye, Markush formulae.

Fig. 4: Plausibility used by the UK Courts to take the juice off further patents

G 2/21

Against this backdrop, G2/21 was eagerly awaited to provide an answer to the fundamental question: when can post-published evidence be relied upon to support a technical effect for establishing inventive step? Plausibility was considered relevant to answering this question by the referring Technical Board of Appeal (TBA) 3.3.02, which identified a divergence in previous decisions in the use of this concept to determine whether post-published evidence can be relied upon. The specific questions were as follows:

If for acknowledgement of inventive step the patent proprietor relies on a technical effect and has submitted evidence, such as experimental data, to prove such an effect, this evidence not having been public before the filing date of the patent in suit and having been filed after that date (post-published evidence):

1) Should an exception to the principle of free evaluation of evidence (see e.g. G 3/97, Reasons 5, and G 1/12, Reasons 31) be accepted in that post-published evidence must be disregarded on the ground that the proof of the effect rests exclusively on the post-published evidence?

2) If the answer is yes (the post-published evidence must be disregarded if the proof of the effect rests exclusively on this evidence), can the post-published evidence be taken into consideration if, based on the information in the patent application in suit or the common general knowledge, the skilled person at the filing date of the patent application in suit would have considered the effect plausible (ab initio plausibility)?

3) If the answer to the first question is yes (the post-published evidence must be disregarded if the proof of the effect rests exclusively on this evidence), can the post-published evidence be taken into consideration if, based on the information in the patent application in suit or the common general knowledge, the skilled person at the filing date of the patent application in suit would have seen no reason to consider the effect implausible (ab initio implausibility)?

Due to the structure of the questions, the EBA could have answered question 1) in the negative and got away without discussing the tricky plausibility questions 2) and 3). And it seems that they indeed pondered this possibility. Fortunately, though, the EBA did not just keep the principle of free evaluation of evidence free from any exceptions. They even went to some length to deliver a wide-ranging decision which makes several points about:

a) free evaluation of evidence,

b) the burden of proof for technical effects,

c) the concept of plausibility,

d) post-published evidence in the context of inventive step, and

e) post-published evidence in the context of sufficiency.

Unfortunately, though, it is actually quite difficult to understand how to apply these general observations to the key issues in the referral. The EBA’s opinion is also relatively light on reasoning which will make it difficult to apply the conclusions to new scenarios. In the following, we comment on what we consider to be the key findings of the EBA on a) – e).

a) Free evaluation of evidence

The EBA reviewed EPO and national law and concluded at reasons 55 and 56 that:

…the principle of free evaluation of evidence qualifies as a universally applicable principle in assessing any means of evidence by a board of appeal. Hence, evidence submitted by a patent applicant or proprietor to prove a technical effect relied upon for acknowledgement of inventive step of the claimed subject-matter may not be disregarded solely on the ground that such evidence, on which the effect rests, had not been public before the filing date of the patent in suit and was filed after that date.

So at least the answer to question 1) is clear: the EPO’s door is open to post-published data, at least in certain circumstances. Guidance on when post-published data can be accepted is provided in d) and e) below.

b) Burden of proof for technical effects

The issue of who bears the burden of proof for technical effects achieved by the invention is hotly contested by Patentees and Opponents before the EPO. The EBA cut through this Gordian knot by summarizing established case law in a way that opponents will find useful at reason 26:

According to the established case law of the boards of appeal (see Case Law of the Boards of Appeal of the EPO (CLB), 10th edition, I.D.4.2, and the decisions therein) it rests with the patent applicant or proprietor to properly demonstrate that the purported advantages of the claimed invention have successfully been achieved.

Reason 58 makes a similar point: a patent applicant or proprietor must demonstrate [plausibility] in order to validly rely on an asserted but contested technical effect. This doesn’t sit easily with, e.g. T 1797/09 discussed at III.G.5.1.1 of the CLB frequently cited by patentees. Unfortunately, the EBA doesn’t provide much detail or reasoning on this point.

c) The concept of plausibility

Reason 58 makes clear that plausibility is not a requirement for patentability itself or an exception to free evaluation of evidence, but is at best a factor in deciding whether an effect can be relied upon:

The Enlarged Board considers the conceptional notion inherent in the term “plausibility”, which is often used as a generic catchword, as not being a distinct condition of patentability and patent validity, but a criterion for the reliance on a purported technical effect. In this sense, it is not a specific exception to the principle of free evaluation of evidence but rather an assertion of fact and something that a patent applicant or proprietor must demonstrate in order to validly rely on an asserted but contested technical effect.

This is a significant divergence from e.g. the approach adopted in the UK, where plausibility has evolved into a separate non-statutory patentability test (see above). It also seems to undermine the critical role ascribed to plausibility by the referring TBA, who framed their questions 2) and 3) using the term “plausibility” after a detailed review of the diverging use of this concept in earlier decisions. In contrast, the EBA did not use it in their Order and referred to it somewhat dismissively as a “generic catchword”. At this point in the decision, one might start to wonder whether the elephant of plausibility is being slowly led from the room – but as we will see, the EBA do not manage to remove it entirely.

d) Post-published evidence in the context of inventive step

The EBA then turned to the question of when post-published evidence can support an effect for inventive step, while studiously avoiding the term “plausibility”.

After a lengthy review of EPO case law which the referring TBA found divergent because different standards were applied to plausibility (i.e. in order of increasing strictness for patentee: no plausibility < ab initio implausibility < ab initio plausibility), the EBA at reason 71 identified common ground in all these cases:

…the core issue rests with the question of what the skilled person, with the common general knowledge in mind, understands at the filing date from the application as originally filed as the technical teaching of the claimed invention.

Following this analysis, at point 2 of the Order, they provide the following guidance:

A patent applicant or proprietor may rely upon a technical effect for inventive step if the skilled person, having the common general knowledge in mind, and based on the application as originally filed, would derive said effect as being encompassed by the technical teaching and embodied by the same originally disclosed invention.

It is not entirely clear how to apply this test on inventive step – even the Board accepts at reason 95 that the criteria are “abstract” and that a decision must be made “based on the pertinent circumstances of each case”. (Who would have thought that?) On a literal understanding, the “derivable” test seems to be reminiscent of the low bar for accepting post-published evidence for effects without evidence/explicit disclosure in the application using the lax “no plausibility” standards. One might therefore assume that a different conclusion would be reached using the new test than in earlier TBA decisions applying the strict “ab initio plausibility” standard. On the contrary: the EBA indicates at reason 72 that applying their test leads to the same conclusions in all the decisions identified as divergent by the referring TBA!

Applying this understanding to the aforementioned decisions, not in reviewing them but in an attempt to test the Enlarged Board’s understanding, the Enlarged Board is satisfied that the outcome in each particular case would not have been different from the actual finding of the respective board of appeal. Irrespective of the use of the terminological notion of plausibility, the cited decisions appear to show that the particular board of appeal focussed on the question whether or not the technical effect relied upon by the patent applicant or proprietor was derivable for the person skilled in the art from the technical teaching of the application documents.

Thus, according to the EBA applying this test should allow accepting post-published evidence for effects without evidence (or even explicit disclosure) in the application, in line with e.g. reason 2.5.2 of T 31/18. At the same time applying the test should also lead to the same conclusion as in T 488/16 reason 4.5, where post-published evidence was not accepted for effects explicitly asserted but not evidenced in the application. While the EBA still saw common ground between these decisions, it will remain a bit of a mystery how their opposite outcomes can be reconciled, if at all possible. At least, it is rather unclear how exactly the EBA’s new test is to be applied.

Although the EBA doesn’t seem to give express guidance, one clue derivable from the decision is in the reasoning on sufficiency of disclosure discussed below.

e) Post-published evidence in the context of sufficiency of therapeutic effects

First and foremost, whether the inventive step or sufficiency is at issue depends on the claims: effects not specified in the claims are dealt with under inventive step while effects specified in the claims are dealt with under sufficiency. Concerning sufficiency, the EBA held at reason 74 that

…it is necessary that the patent at the date of its filing renders it credible that the known therapeutic agent, i.e. the product, is suitable for the claimed therapeutic application.

Note here that the “generic catchword” has snuck back into the EBA’s reasoning albeit under the synonym for plausible, “credible”. The elephant seems not to have gone after all. After reviewing several TBA decisions, the EBA states at reason 77 that:

…the scope of reliance on post published evidence is much narrower under sufficiency of disclosure compared to the situation under inventive step. In order to meet the requirement that the disclosure of the invention be sufficiently clear and complete for it to be carried out by the person skilled in the art, the proof of a claimed therapeutic effect has to be provided in the application as filed, in particular if, in the absence of experimental data in the application as filed, it would not be credible to the skilled person that the therapeutic effect is achieved. A lack in this respect cannot be remedied by post-published evidence.

Thus, a relatively strict standard is to be applied for supporting an effect using post-published data for sufficiency of disclosure. To use the referring TBA’s terminology, at least ab initio plausibility seems to be required. Inventive step meanwhile seems to require a lower standard: while the test is not entirely clear, the effect must be “derivable as encompassed by the technical teaching and embodied by the original invention”. Given that the EPA explicitly requires no proof of the effect in the context of inventive step, this may keep the door open for (credibly?) asserting a certain effect in the application as filed and providing the data later.

Conclusion

In summary, G 2/21 generally provides ammunition for opponents seeking to place the burden on patentee for demonstrating a technical effect. It also clearly places the burden on patentee for sufficiency of therapeutic effects, and makes it difficult to address this issue with post-published data. While it is not entirely clear how to apply the test for post-published data concerning inventive step, the bar seems to be lower than for sufficiency.

What does all of this mean in terms of the future of plausibility in EPO Case Law? Has the elephant finally left the room?

Fig. 5: Whether the elephant is really gone for good is in the eye of the beholder.

Even after a thorough reading of G 2/21, this is tough to answer. Clearly, the Enlarged Board does not like plausibility as a concept or criterion. But what, if anything, will replace it?

Perhaps it is time to update the African proverb “when elephants fight, it is the grass that suffers” to:

When the EBA fights the plausibility elephant, it is legal certainty that suffers.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Patent Blog, please subscribe here.

Good stuff. Thanks for getting the review out so fast. Thinking about different standards of credibility/plausibility for sufficiency as opposed to patentable inventivity, and why that might be, is it not proper for public policy reasons to require in an application as filed a higher level of credibility/plausibility under Art 83 EPC than under Art 56 EPC?

I mean, when the USA switched from First to Invent to a First to File patent law, there was a lot of hand-wringing about the mischief it would do, by obliging competitive Applicants to file ever more prematurely, on ever more speculative solutions to technical problems. A strict line on sufficiency of disclosure restrains nuisance filings that are nothing more than speculative. A less strict line for inventive activity, by contrast, can encourage early filings, leading to earlier A publications and speedier promotion of further innovation.

Identifying the technical effect (of the distinguishing feature) and proving that this effect is credibly achieved over the entire breadth of a claim are two distinct (albeit connected) steps in the PSA. Since always I guess. Only after completing these two steps, the objective technical problem can properly be formulated. The diverging case law that led to the referral, stemmed from different reactions of boards not to the flexibility traditionally accorded by the EPO to identify an effect. But to how applicants/patentees then try to prove this effect. On the other hand, the EBA could not shrink the freedom in identifying technical effects because the possibility to invoke even undisclosed effects is the (unavoidable) dark side of the problem-and-solution approach, as long as applicants are confronted with prior art unknown on filing. So rewriting the rules for the identification of the technical effect would have attracted the PSA into a black hole. And the EBA has smartly solved the impasse by reiterating the approach already applied by EPO examiners and boards (all technical effects can be invoked upon condition that they do not change the nature of the invention). Nothing new here. Concerning the possibility to prove the effect, I find it weird that the EBA has never mentioned the concept that the referring board had, though, highlighted in bold, i.e. the fact that the post published evidence is the exclusive proof for the effect. Here is where case law diverged in my opinion. Faced with the need to prove effects that are not supported by data already present in the application, some boards adopted a stricter approach and requested a trace of credibility in the application or existing knowledge to accept the (unavoidable) post-published evidence. Others took less strict a stand, and refused the post-published evidence only in presence of objective and verifiable doubts. Some others did not ask questions, and systematically accepted the evidence (which to me is the approach closer to a real respect of the free evaluation of evidence). I’m not sure that the EBA opinion helps predicting how boards will react next time they are faced with this situation (again where the post-published evidence is the exclusive proof of a given effect). This is unrelated with the step of identifying the effect (and the abstract idea of what a skilled person would read in the application). But rather with how I can prove the effect that I decide to invoke. Incidentally, I surmise this is the reason why for sufficiency the bar is higher. I choose how to draft the application/claims. And I bear the consequences of appropriately proving the effects that I decide to mention in the application. Comparison with unknown prior art has no bearing here.

Thanks to Thorsten for a pleasant and informative contribution on G 2/21.

In general it is expected from decisions of the EBA to clarify a legally confused situation. I am not convinced that this aim has been achieved with G 2/21.

It is an understatement for the EBA to talk about “abstract considerations”. It will undoubtedly lead to several “dynamic interpretations”.

It is difficult to see how this decision will help solve the problems sometimes posed by late submissions trying to prove an effect when the originally filed documents does not appear completely “credible”, not to say “plausible”.

Whilst it can be agreed with the EBA that the concept of “plausibility” is absent from the EPC, this also applies to the concept known under “problem-solution approach” when assessing IS.

I did not find any compelling reason why “plausibility” should not be relied upon, but application of the PSA is deemed compulsory. The difficulty of the PSA lies in the determination of the closest prior art and as a consequence in the determination of the “objective technical problem” which results from the effect of the differences with the closest prior art.

It can be agreed that the decision on “plausibility”, “credibility”, you name it all, should not, as such, depend from the prior art revealed during the search.

When applying the famous “three-point-test”, cf. H-V, 3.1, T 2311/10 held that the “problem” to be taken into account in step 2) is the problem as defined originally in the application and not the “objective problem” when it comes to asses inventive step. If the latter would be taken into account, it would made the assessment of Art 123(2) dependent from the state of the art, which is not acceptable. This should apply mutatis mutandis to the assessment of IS in presence of late filed submissions.

In this respect relying on what is “being encompassed by the technical teaching” is understandable, but whether it is “embodied by the “same” originally disclosed invention” is anything but easy to follow, as the invention is looked at under a different light with a different closest prior art and hence the effect might not be the same as that originally claimed.

Furthermore, limiting the consideration to IS does not seem to make sense either. See G 1/03 and T 2001/12. Sufficiency of disclosure is a related issue, depending on the wording of the claim, i.e. claimed or unclaimed effect.

If an effect is claimed, but is not credibly achieved, then the objection should be lack of sufficiency. If an effect is not claimed, but the object of the invention is not credibly achieved, then the objection should be lack of IS.

It is also worth mentioning T 59/08. The conclusion drawn by the board in this case is interesting. The Board considered that less stringent requirements for assessing sufficiency of disclosure of the claimed combination of features would on the other hand require stronger arguments in favour of novelty and inventive step, especially if some parameter values are necessary to distinguish the claimed subject-matter from the prior art and considered essential for providing a technical effect vis-à-vis the prior art. See Point 2.7 of the reasons.

Another interesting decision is T 1036/09. Although an effect is claimed, and hence the objection should be, according to G 1/03, lack of sufficiency, the board was however of the opinion that it was more appropriate to consider the critical issue of the present appeal proceedings under the requirements of Art 100(a) /Art 56. See Point 4. of the reasons.

There is thus a series of decisions which show that strictly keeping out of sufficiency, even when dealing with post-published evidence, was not the best position to be adopted by the EBA.

The ‘three point test’ is long gone as a relevant consideration. Only the ‘Gold Standard’ is now used.

Much food for thought in the piece, and in that last comment.

As to an Opponent forcing a re-tuning the OTP and as to technical effects undisclosed in the application as filed, I recall a lecture in or around 1991 about a case which survived opposition only because the Applicant had noted (in the application as filed) a fifth technical effect. Opponent (using prior art new to the case) was able to persuade the Board that the first to fourth effects were not enough to fend off the attack on validity. Patent owner, however, was able to save the patent thanks to the fifth effect, announced in the application as filed. What do we learn from this, asked the lecturer. As patent drafter, one should mention in the application as filed all the technical effects that your inventors can identify.

I’m not in chem/bio, myself. In that area, Attorney Since a While, has the TBA case law moved on, I wonder, from what it was in 1991, and to the benefit of Applicants currently? Or is my understanding of it flawed?

As far as I know, IS analysis is still effect-centric, where the “effect” is the one chosen by the applicant/patentee. This is the difficulty opponents are faced with, as they are called upon challanging the scientific merit of effects they cannot anticipate. Some decisions (e.g. T1317/13, referring to the older T21/81) tried to re-balance the situation by invoking a softer version of the one-way-street approach according to which unexpected effects (i.e. those that patentees typically pull out from the hat after grant, and that are seldom disclosed in the application as filed) can never make an otherwise obvious product claim inventive. But this way of looking at things seems to be poorly followed by ODs and boards. All in all, the leading case law is still applicant/patentee friendly on this point. This is one of the reasons why I’m a bit unsatisified with how the EBoA has framed the opinion. Their flimsy thoughts on the choice of the effect combined with the absence of a clear position on admissibility of post-published evidence when this is the sole proof of (undisclosed) effects, does not make the current situation advance much, I’d say.

To me this decision reads like “please proceed, there is nothing to see here”. Some kind of “there is no conflicting case law, just the different results of diverging fact patterns”. In a way it’s a “weiter so” and not a guidance.

For the pharmaceutical applications, however, it’s a real downer as I see the decision being interpreted to be read on therapeutic effects of not only known therapeutic agents (2nd medical use cases) but to all kinds of therapeutic effects also for new therapeutic agents. So a claim like “substance X for use in treating cancer”, where substance X is new and the examples only show e.g. two different kind of cancer cell lines might be faced with more “credibility” objections than before.

I do not agree with the relationship proposed by Mr Thomas between the concept of plausibility and the problem-solution approach, it think it blurs the issue. The concept of plausibility has arisen from the unpredictable link between structure and biological effect (or function) in the bio/pharma sector but it is not limited to this field. It is also used more recently in IA applications, in which the output of the IA is unpredictable from the data feed to the IA. This is an objective situation.

This does not justify the creation of a separate validity condition – creating another validity condition is a fraught proposal, it adds boundary issues and complexity, as clear from the discussion in the EPO case law as to which of the sufficiency or inventive step should be the relevant condition.

But the unpredictable link between structure and effect determines a different context to those where the link can be explained, as in mechanical/electrical fields. It makes it a key issue to define who has the burden of proof, and this is where the plausibility (or credibility) of the effect comes into play. This is independent from the application of the problem-solution approach. Just look at the Amgen v Sanofi case currently before the US Supreme Court. The case precisely arises from the unpredictable link between function and structure for antibodies, and it is before the US Supreme Court because this is a key component of the balance of interest between the patent owner and third parties, irrespective of the approach used to assess inventive step/obviousness.