On 24 August 2022, Nicholas Caddick QC (sitting as a Deputy High Court Judge in the Intellectual Property Enterprise Court) handed down his decision in Vernacare Limited v Moulded Fibre Products Limited [2022] EWHC 2197 (IPEC), a case on open topped washbowls made from moulded paper pulp, such as those used in hospitals, care homes and nursing homes. The judgment addresses the characterisation of the skilled person, obviousness (including the impact of commercial success as a secondary consideration) and infringement on equivalence.

Background

Vernacare and Moulded Fibre (“MFP”) are competitors in the moulded pulp washbowl field. Vernacare owns two patents, GB 2446793 (the “793 Patent”) and GB 2439947 (the “947 Patent”), both with a priority date of 2006, which relate to the shape and composition of pulp washbowls. Vernacare started infringement proceedings against MFP for its washbowl product. For the 793 Patent, MFP ran a squeeze argument between non-infringement and obviousness over the common general knowledge. For the 947 Patent, MFP accepted that its washbowl infringed, but argued that the patent was invalid.

Vernacare had previously asserted the 793 Patent against Environmental Pulp Products ([2012] EWPCC 41), where HHJ Birss QC (as he then was) held the patent valid and infringed by some products, but not others. The findings of fact were not relevant to this case as the products and evidence were different, but matters of law, and in particular issues of construction, were relevant, given the usual practice for one judge to follow another’s finding, unless the latter judge was convinced that those findings were wrong.

The 793 Patent: Doctrine of Equivalents and the Formstein Defence

In 2006, single-use pulp moulded containers were used in care settings as bed pans, but not as washbowls. The 793 Patent explains that one of the reasons is that washbowls need to hold a greater volume of liquid (up to four litres) and existing designs, which only incorporated a lip, would break when carried.

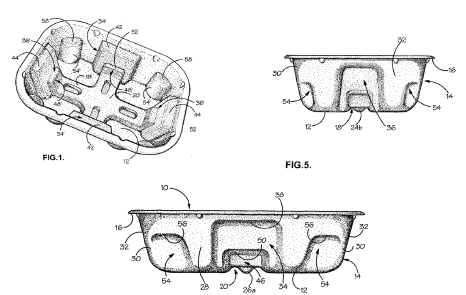

The solution proposed by the 793 Patent is a washbowl with inwardly projecting recesses on opposite sides of the bowl, as shown in Figure 1 below. These recesses allow the washbowl to be lifted, and provide greater structural rigidity, with the near vertical edges of the recess being particularly important to this rigidity.

Figure 1 Washbowl with recesses from the 793 Patent

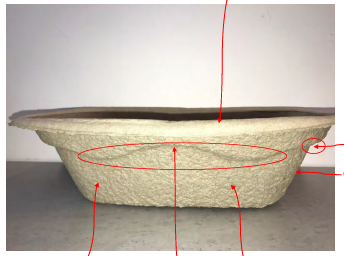

The MFP washbowl does not have separate recesses; instead it has single, undulating, ridge that runs around the whole bowl, as shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2 MFP washbowl

The issues in dispute were whether the MFP washbowl contained “an enclosing wall comprising recesses” and whether those recesses formed “grip means” for “facilitating lifting”. The judge first considered whether the MFP washbowl infringed under a ‘normal’ (that is to say, purposive) construction. Given the 793 Patent claimed “recesses” there had to be multiple recesses, and the wording of the specification meant that these recesses had to have near vertical sides. As the MFP washbowl was a single ridge with no near vertical sides, it did not infringe on a normal construction. In making this finding, the judge was in agreement with HHJ Birss QC, who had found that a similar, single ridged product did not infringe. However, and in case he was wrong on this first issue, the judge found that the ridge was clearly a grip that facilitated lifting.

Having considered infringement on a normal basis, the judge proceeded to assess infringement by equivalence. This was done by way of the three questions set out by Lord Neuberger in Actavis:

- Does the variant achieve substantially the same result in substantially the same way as the invention (i.e. the inventive concept revealed by the patent)?

- Would it be obvious to the skilled person at the priority date, knowing that the variant achieves substantially the same result as the invention, that it does so in substantially the same way as the invention?

- Would the skilled person have concluded that the patentee nonetheless intended that strict compliance with the literal meaning of the relevant claim of the patent was an essential requirement of the invention?

The answer to the first two questions requires the identification of the patent’s inventive concept. Vernacare submitted that it was “to provide a moulded paper pulp bowl large enough to be used as a washbowl, with a grip means in the form of recesses”, whilst MFP considered it “the use of recesses with vertical sides”. However, the judge did not consider it necessary to decide this point, as Vernacare would fail on two separate points; the answer to the third question would be ‘Yes’, and MFP could rely on the Formstein defence.

The Formstein defence (named after a decision in a German case) is where an alleged infringer is able to escape infringement under the doctrine of equivalents, if the scope of the claim is so expanded as to read onto the prior art. There have been obiter discussions of its availability in other UK cases (e.g. by Birss LJ in Facebook v Voxer [2021] EWHC 1377, and by HHJ Hacon in Technetix v Teleste [2019] EWHC 126 (IPEC)) but in neither case was the defence determinative as the patents were found invalid.

MFP argued that a moulded bowl with an undulating ridge running around the side walls was part of the common general knowledge, a point with which the judge agreed. As the MFP washbowl simply implemented this teaching, it could avail itself of the Formstein defence. Alternatively, the skilled person would have concluded that the patentee did intend strict compliance with the wording of the claim, as otherwise the claim would be invalid for obviousness.

Thus, the 793 Patent was held to be valid but not infringed.

The 947 Patent: The Skilled Person and Obviousness

The other reason that pulp bowls were not previously used as washbowls was that soaps would penetrate, and thus disintegrate, the pulp structure. The solution proposed by the 947 Patent is the use of a fluorocarbon sizing agent as an additive to the pulp mix. MFP argued that this was obvious over two pieces of prior art, both Japanese patent applications that disclosed the use of fluorocarbons in pulp food containers, the fluorocarbons being added to improve resistance to water and oil.

The key issue in deciding whether these prior art documents rendered the 947 Patent obvious was the identity of the skilled person and their common general knowledge. MFP argued that the skilled person would have had a background in chemistry, and specialised in pulp compositions. As such, this skilled person would have been aware of fluorocarbons, and that they could prevent the degradation of pulp by detergents. By contrast, Vernacare argued that the skilled person was a designer, who was aware of typical compositions of pulp products, but was not an expert in pulp formulation and did not have a sufficient knowledge of chemistry to know what additives could be added to achieve particular properties in the final product. The judge preferred Vernacare’s characterisation, finding that none of the witnesses suggested that pulp moulding companies would employ an individual with a background in chemistry, instead seeking external advice from a specialist as and when necessary.

Therefore, the skilled person when presented with the prior art, would not think of extending the use of a fluorocarbon from an oil and water resistant food container, to a detergent resistant washbowl, as they would not realise that oil and water resistance may also confer detergent resistance.

Commercial Success and Long Felt Need

Vernacare also tried to show long felt want and commercial success as secondary indications that the 947 Patent was not obvious. Vernacare submitted evidence trying to show that the need for detergent resistant disposable pulp washbowls had been felt since other pulp products had first been introduced in care settings in the 1960s. In this regard its main argument was that the use of non-disposable washbowls which required cleaning increased the risk of cross-contamination. It also submitted figures showing it had sold over 27.5 million units in 2018.

The judge considered the factors on secondary indications set out by Laddie J in Haberman v Jackel [1999] F.S.R. 683 (and approved by Jacob LJ in Schlumberger v Electromagnetic Geoservices [2010]

EWC Civ 819). He noted that the evidence did not suggest that the lack of disposable wash bowls was a problem in 2006, since, despite the hypothetical problem of cross-contamination with reusable bowls, there was no evidence of any actual infections. The evidence that Vernacare did submit was post-priority and largely originated from Vernacare itself as part of its marketing efforts for its new product.

With regards to Verncare’s sales, a single number of units in isolation meant nothing. The judge knew nothing of the profit margin or the overall size of the market, and there was no evidence on whether these sales were due to the originality of the invention or the success of its marketing. Accordingly, the judge did not consider there to be any support for Vernacare’s case on lack of obviousness. Given this issue required a witness of fact from each party, it will be interesting to see if Vernacare is penalised in costs (assuming that the parties do not settle on costs).

Notwithstanding the lack of success of Vernacare’s pleas of commercial success and long-felt need, the 947 Patent was held to be valid (and, as noted above, infringement was admitted)/

Conclusion

This judgment is important as it represents the first case where a Formstein defence is determinative of the issues, and confirms that this defence is available in the English courts. It also provides a useful example of the nature of evidence required when arguing for secondary indications of obviousness.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Patent Blog, please subscribe here.