As readers will be well aware, one of the points on which the courts of various European countries diverge, is whether or not the prosecution history of the patent at hand may be taken into account to interpret its scope of protection. For example, the UK Supreme Court, in its landmark judgment of 12 July 2017 (Pemetrexed), in a case decided by applying English, French, Italian and Spanish law, came to the following conclusion:

“In my judgment, it is appropriate for the UK courts to adopt a sceptical, but not absolutist, attitude to a suggestion that the contents of the prosecution file of a patent should be referred to when considering a question of interpretation or infringement, along substantially the same lines as the German and Dutch courts. It is tempting to exclude the file on the basis that anyone concerned about, or affected by, a patent should be entitled to rely on its contents without searching other records such as the prosecution file, as a matter of both principle and practicality. However, given that the contents of the file are publicly available (by virtue of article 128 EPC 2000) and (at least according to what we were told) are unlikely to be extensive, there will be occasions when justice may fairly be said to require reference to be made to the contents of the file. However, not least in the light of the wording of article 69 EPC 2000, which is discussed above, the circumstances in which a court can rely on the prosecution history to determine the extent of protection or scope of a patent must be limited.”

To sum up, the UK Supreme Court found that, since the prosecution history is not one of the interpretative criteria enshrined in article 69 of the European Patent Convention (“EPC”), recourse cannot be had to the prosecution file as a general rule, although there may be exceptional situations where delivering justice in the case at hand may justify its use.

Interestingly enough, prosecution history has been under the spotlight in a case recently decided by the Barcelona Court of Appeal. For the purpose of this blog, it will suffice to summarise the following facts:

Lekue®, an innovative manufacturer of kitchen utensils based very close to this authors’ hometown, filed an infringement action based on EP 2193731 B1 (“EP ‘731”) against a third party that was marketing silicone cases for steaming food in microwave ovens using the papillote technique. Claim 1 of EP ‘731 reads as follows:

“1. A utensil for containing foodstuffs, applicable to cooking in a microwave oven, of the type comprising a receptacle (10) made of an elastomeric material for containing foodstuffs, with an access opening and covering means for covering said access opening, wherein the receptacle (10) is formed by a bottom wall (1) in the shape of a channel defining side opening edges (5, 6) which is connected at its ends to end walls (2, 3) defining respective end opening edges (8, 9), said side and end opening edges (5, 6, 8, 9) defining said access opening at a higher level than said bottom wall (1), characterized in that:

said end opening edges (8, 9) of said end walls (2, 3) have a convex shape with lower ends at the level of said side opening edges (5, 6) of the bottom wall (1) and central portions which are raised to a level above the side opening edges (5, 6);

said covering means comprise at least one lid (20, 30, 40) having at least one first side edge (21, 31, 42) adjacent to at least one of the side opening edges (5, 6) of the receptacle (10) and concave end edges (24, 25; 34, 35; 44, 45) resting on the convex end opening edges (8, 9) of the receptacle (10) in a closed position; and said end walls (2, 3) of the receptacle (10) include respective handles (11, 12) laterally extending outwardly in cantilever from the corresponding convex end opening edges (8, 9) forming upper surfaces common therewith, and the or each lid (20, 30, 40) has respective end portions (28, 29; 38, 39; 48, 49) adjacent to said concave end edges (24, 25; 34, 35; 44, 45) and configured to cover and complement said handles (11, 12) in the closed position.”

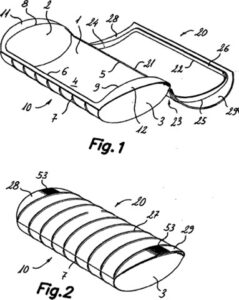

The following drawings may help interpret the claim:

The Barcelona Court of First Instance, in a judgment of 15 December 2020, dismissed the infringement action on the grounds that the allegedly infringing products did not reproduce all the features of claim 1. For the purpose of this blog, it will suffice to focus on the following feature: “a bottom wall (1) in the shape of a channel defining side opening edges (5, 6) which is connected at its ends to end walls (2, 3) defining respective end opening edges (8, 9)”. The defendant successfully alleged before the Court of First Instance that, due to an amendment introduced in the application during prosecution, the element “a bottom wall in the shape of a channel” had to be curved. To sum up, the Court found that the defendant’s product did not reproduce this element, as it found that, in the defendant’s product, that element was not curved.

Lekue® appealed the decision before the Barcelona Court of Appeal, which, in a judgment of 30 March 2022, upheld the appeal. Interestingly, the Appeal Court found that whereas that element may have been of relevance to resolve the technical problem initially exposed in the patent application (a so-called “cooking” problem found in the prior art), it did not have such relevance as to resolve the objective technical problem resulting from the modification of the application, which was to resolve a problem of “holding and security of the container.” In view of this, the Court of Appeal found that it was not correct to interpret the claim as requiring that element to be curved, particularly when taking into account that claim 1 did not mention that requirement, either literally or implicitly.

Also, the Court of Appeal reproached the Court of First Instance for having used the specification, which referred to “curved” in relation to the shape of that element. Again, the Court of Appeal noted that, whereas this reference to a “curved” shape was relevant in the context of the technical problem initially exposed in the application as filed, it was no longer relevant to interpret amended claim 1 in view of the modification of the technical problem that took place during prosecution. The thinking of the Court of Appeal is encapsulated in the last sentence of paragraph 48: “To conclude, these passages of the specification, which could not be modified, cannot serve to limit the technical element of the claim that was modified.”

This interesting case illustrates that, sometimes, it is very difficult to draw the fine line between “interpreting” the claim in the context of the specification and “importing” into the claim an element of the specification.

All in all, its main teaching is that, in Spain, article 69 of the EPC and the Protocol do not seem to be the end, but rather just the beginning, of the discussion when it comes to determining scope of protection.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Patent Blog, please subscribe here.

If there is one case in which the file history should have been taken into account it is the famous pemetrexed case.

The applicant was in a hurry to get a patent but only had disclosed pemetrexed disodium. When he claimed pemetrexed in general he rightly faced an objection under Art 123(2). Showing his ignorance of the EP procedure, Lord Neuberger found this objection unjustified.

The applicant could have presented further data rendering plausible the use of other salts. He manifestly did not have any corresponding experimental data to support his attempts to claim more than what he had actually disclosed. It is only later that he sought of the applicability of its teaching to other salts.

It is interesting to note that in first instance the district court of The Hague did consider that the applicant’s attitude during prosecution did not warrant a broader prosecution. This decision was regrettably set aside by the court of appeal, which aligned its decision to that of other courts.

For the case at stake, it shows that each national court has its own DoE. The presence of curved sides does not seem essential and the decision of the court of appeal is fully understandable.

I possess the patented device and the curved part is of no importance. What matters is the lid and the handles

Attentive, I am amazed what a full-blown meal the judges made of this trivial inconsistency between the description and the claim. I ask you, reversal on appeal. What’s next, an appeal to the national Supreme Court?

I fear that such cases only serve to encourage the EPO in its crusade against any sort of “disconformity” whatsoever, using the argument that even the most trivial of inconsistencies results in a 10-fold increase in the cost of litigating a patent issued by the EPO.

As you say, it doesn’t have to be like this, does it?