… that is the question in recent ‘Dutch discovery’ proceedings in a patent dispute between beer giants Anheuser-Busch Inbev (‘ABI’) and Heineken. Well, sort of: the legal question was if ABI would be granted access to documentation seized at Heineken’s premises in the Netherlands. The Hague Court’s Preliminary Measures Judge’s answer did all but refresh the parts ABI tried to reach.

To get back to the title of this post, ‘Dutch discovery’ is also not really spot on. In the Netherlands there exists no U.S. style pre-trial discovery. Dutch ‘discovery’ is to shoot first (by securing information on the basis of an ex parte court order), and discover later (in follow-up inter partes access proceedings). Other European states allow for similar measures to preserve evidence (partly thanks to the EU Enforcement Directive). And the funniest thing about Europe? It’s the little differences. While, like in France, we got the metric system, a Dutch discovery still tastes a little different from a saisie–contrefaçon.

A Dutch discovery starts off with a seizure (well, often: there are some options to request an order to produce information in pending proceedings). A party seeking evidence to (further) substantiate its infringement claim, can request the court permission to seize documentation and samples and make a detailed description of products and processes at the alleged infringer’s premises. In short, to receive permission from the court – to be precise: one judge, the Preliminary Relief Judge – the patentee should make the alleged infringement sufficiently plausible and specify the documentation it seeks to secure. If granted, the patentee is not (yet) allowed to access the secured information (which will be stored at a custodian).

To get access (or: exhibition), the seizing party has to file a separate claim (usually in merits or summary proceedings following the seizure). In those access proceedings the court will assess if i) the party has a legal interest in (access to) the documents, ii) the documents concern a legal relationship to which the party is a party (patent infringement being considered such a relationship), iii) the documents the party seeks access to are sufficiently specified, while iv) protection of confidential information should be ensured. The threshold to get access is higher than to get a seizure request granted, but lower than to get an injunction granted in PI proceedings.

The ABI/Heineken decision did not revolve around the often hotly debated specification requirement. Case law provides some guidelines on what can be considered sufficiently specified (e.g. documents do not need to be named individually, if their subject-matter is carefully delineated). In practice, the bailiff often uses certain keywords (related to the infringing acts) to select documents during the raid on the alleged infringer. In the same practice, however, keywords are not always (restrictively) used, resulting in the seizure of (seemingly) a large amount of data. In such cases standard arguments back and forth in the access proceedings are: there was a boundless seizure to create a large fishing pond (party seized upon); there was some selection, while a broad seizure was necessary to prevent destruction of evidence (seizing party). A too ‘broad’ seizure, and the absence of a specification in the access proceedings, can result in access being denied all together.

For example, a recent judgment in access proceedings describes the seizure of a complete server with all available data of 36 entities within a group of companies, all emailboxes of employees, archives of 200 (former) employees, and Sharepoint environments, totaling 145 terabyte of data or 232,000 encyclopedias (which must not have been the Encyclopedia Britannica, as a 1000 fit on a terabyte). The Hague Court of Appeal considered that the search terms to be used to search the seized documents were not specified. In view of the important role these terms play in the execution of the access claim, this meant that the documents to which the access request pertained were not sufficiently determined. The Court of Appeal could not decide with a sufficient degree of certainty i) to which documents the claims related, ii) whether the conditions for granting the claims were met and iii) or whether there were compelling reasons to deny the access claim. Access was denied.

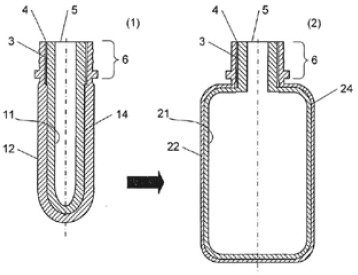

Back to beer: ABI asserted that they should get access to the evidence seized, because it was sufficiently plausible that Heineken’s product fell within the scope of one of its patents (EP 2 152 486). ABI’s patent and Heineken’s product concern so-called bag-in-containers, a liquid dispensing packaging in which beer is contained in a bag inserted in a container.

Fig. from the patent: bag-in-container (2) and preform for its manufacturing (1)

Fig. from the patent: bag-in-container (2) and preform for its manufacturing (1)

The Hague Court’s Preliminary Measures Judge dismissed ABI’s access request. In particular noteworthy is how the Judge considers the ‘legal interest’ requirement while balancing the interests of ABI and Heineken. The Judge notes that in summary proceedings such as these (in Dutch: kort geding), there should always be a balancing of (urgent) interests. The patentee (i.c. ABI) has an interest in getting access to documents to determine if initiating actual infringement proceedings makes sense, while the alleged infringer (i.c. Heineken) has an interest in the protection of its trade secrets. Factors to consider in that regard are the value of the trade secrets and that access, if granted, is irrevocable, while it is – according to the Judge: “commonly known” – notoriously difficult to prove the misappropriation of trade secrets (for example of those acquired via access proceedings).

The Judge further considers there is less reason to order the exhibition in summary proceedings if the alleged infringement or the patent appears to be less strong, while the trade secrets set against it seem stronger. Access will usually have to be refused in summary proceedings if there is a serious, non-negligible chance that the patent is invalid or if it is likely that the patentee’s claim / scope of protection interpretation will not be followed in merits proceedings. In such case, the patentee will first have to test its (interpretation of the) patent in merits proceedings. This will only be different if no real or insufficiently important trade secret is made plausible by the alleged infringer.

ABI’s access claims are dismissed on the basis of aforementioned balancing of (urgent) interests. The Judge considers that Heineken argued, and ABI did not dispute, that Heineken’s “trade secrets of very considerable value are at stake”. ABI, on the other hand, “proposes a shaky patent with also a shaky infringement interpretation, while [ABI] certainly did not act expeditiously”. According to the Judge there is a good chance that the merits court will find that ABI’s patent is not infringed. At the same time there is a serious, not to be neglected chance ABI’s patent will be held invalid in merits proceedings. Finally, ABI waited such a long period to act against Heineken’s product, which has been on the market since 2014, that there is no hurry in granting access.

In the end ABI was served a flat beer: after having been denied any access to the seized documentation, ABI did receive two samples of Heineken’s product…which were freely available on the market.

The decision is available here (Dutch).

Disclaimer: the author’s firm represented Heineken in this case.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Patent Blog, please subscribe here.