The recent Apple v. Baili case has generated a wide interest in design patents. This article discusses developments on judicial standards for determining design patent infringement applied in Apple v. Baili, and some implications from this case. Such standards involve how to determine distinctive features, what to be considered to differentiate a functional feature, what elements may affect the degree of freedom of designers (space of design), and etc.

1. Background

In December 2014, Baili, a domestic start-up smartphone maker, filed a complaint to the Beijing Intellectual Property Office (“BIPO”), alleging that iPhone 6 and iPhone 6 Plus (the “accused products”) infringed upon Baili’s Chinese Design Patent No. CN20143009113.9 (the “’113 patent” or “asserted patent”) and asked for permanent injunction against the accused products. Apple promptly filed a petition challenging the validity of the ‘113 patent before the Patent Re-examination Board (“PRB”) of the State Intellectual Property Office (“SIPO”) in March 2015.

In January 2016, the PRB issued a decision which upheld the validity of the ‘113 patent but significantly limited the scope of the patent. Shortly thereafter, in May 2016, BIPO issued an administrative penalty decision (“BIPO decision”) finding that iPhone 6 and iPhone 6 Plus infringed the asserted patent and ordered Apple to stop selling these models in Beijing. Apple appealed to the Beijing IP Court (“Court”). In March 2017, the Beijing IP Court rendered its judgment reversing the BIPO decision and finding that Apple’s iPhone 6 and iPhone 6 Plus did not infringe on Baili’s‘113 patent because it did not meet the “ordinary observer test.”

2. The “Ordinary Observer Test”

The sole test for determining design patent infringement in China, as expressed by the Supreme People’s Court (“SPC”) judicial interpretations and case precedents, is whether an “ordinary observer”, who is a hypothetical ordinary consumer supposed to be familiar with the prior art and giving the usual attention of a purchaser, would find the accused products identical or similar to the patented design. Such ordinary observer is not an expert, but one who intends to purchase the patented design or is interested in the subject, with the knowledge level and cognition ability to distinguish the patented design from prior art designs. Such ordinary observer test is very similar to the test for design patent infringement in the U.S. set forth in Egyptian Goddess, Inc. v. Swisa, Inc., 543 F.3d 665 (Fed. Cir. 2008).

The SPC also guided that, before applying the “ordinary observer test”, a court should exclude functional design elements because a design patent protects only ornamental or “non-functional” features. Courts should compare the ornamental features of the design in the context of the claimed design as a whole, and not in the context of separate elements in isolation.

3. Ornamentality v. Functionality

In the case at hand, Baili urged the Court to ignore the dissimilarities identified between the patented design and the accused products (including the home button, the position of the flashlight, audio jack and headphone jack, the ring/silent switch and volume button, and the pattern on the back of the two mobile phones) because, it contended, these elements are all functional and should be excluded from the infringement analysis. The Court disagreed, emphasizing that it considered the following factors in determining whether an element is primarily functional: (i) whether the design is dictated solely by functionality; (ii) whether alternative designs exist to achieve the same function; and (iii) whether the design was chosen for functional rather than aesthetic reasons.

The Court noted that the features found to be dissimilar are ornamental rather than functional, because obvious alternative design choices exist and they present an aesthetically pleasing appearance. Therefore, the Court treated these features as ornamental aspects of the patented design that shall be considered in the comparison.

4. Application of the Ordinary Observer Test to the Accused Products

The Court then applied the “ordinary observer test” and compared the various features of the accused products to the asserted patent and found them sufficiently distinct.

(1) The Most Visually Commanding Features During Normal Use

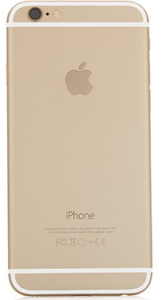

The Court first compared the most notable and prominent features of both designs during normal use, the home button at the bottom of the front screen and the pattern on the back surface, as they dominate the overall appearance of the respective designs. The Court found that while iPhone 6 and 6 Plus have a physical round home button, Baili’s’113 patent adopts a virtual button in a rectangle shape. In addition, iPhone 6 and 6 Plus have plastic-like lines that run across the phone at the top and bottom of the back, while the patented design has no stripe across the back face. The Court implied that an ordinary consumer would easily notice these “most obvious” differences between two designs and find them fairly dissimilar.

‘113 patent iPhone 6 ‘113 patent iPhone 6

(2) The Designer’s Degree of Freedom

In addition, the Court considered the designer’s degree of freedom in developing relevant designs, which depends on whether the prior art is crowded with similar designs.

The Court held that in light of the PRB decision and numerous prior art provided by Apple, the design of the smartphone’s appearance is a crowded field with prior art, and the designer has limited degree of freedom. The Court explained that an ordinary consumer would make a more discriminative examination and comparison of the patented and accused designs, and is more likely to notice minor distinctions between different designs. The Court therefore found non-infringement of the accused products.

(3) Distinguishing Features of the Asserted Patent from the Prior Art

The Court next looked at whether the accused products have copied the particular features of the asserted patent that depart conspicuously from the prior art. The Court indicated that if the accused design does not appropriate all especially the most prominent novel features of the patented design, the accused design is naturally more likely to be regarded as non-infringing. Therefore, such novel features are important in analyzing whether the overall appearances of two designs are identical or similar. When the differences between the claimed and accused design are viewed in light of the prior art, the attention of the hypothetical ordinary observer will be drawn to those aspects of the claimed design that differ from the prior art.

During the PRB proceeding, Apple submitted a large number of prior art references. The height-to-width ratio of rounded corners of the ‘113 patent is very close to those of the prior art and the slight differences between the ‘113 patent and the prior art are unnoticeable in the eye of an ordinary consumer giving such attention as a purchaser usually gives. The PRB nevertheless upheld the validity of the asserted patent by finding two distinctive features of the patent design from the prior art: the floating screen on the front face and the asymmetrical rounded corners with a particular height-to-width ratio, despite the fact that the ‘113 patent consists only of bringing together old elements with slight modifications.

Apple argued that the scope of the patented design is restricted to a very limited range by the PRB decision and that so limited the accused products do not infringe. Apple contended that iPhone 6 and 6 Plus are closer to the two closest prior art references than to the patented design, thus there was no infringement.

The Court ruled in Apple’s favor, finding that most of the similarities between iPhone 6 and 6 Plus and the ‘113 patent, such as the general shape of the devices, the rounded corners, the flat clear screen have been disclosed by the prior art.

The Court held that iPhone 6 and 6 Plus have symmetrical rounded corners with a height-to-width ratio notably different from the patented design. iPhone 6 and 6 Plus contain a similar floating screen on the front face as the patented design though, this small detail does not make comparable visual impression to that the distinct rounded corners do.

Accordingly, the Court concluded that because iPhone 6 and 6 Plus and the ‘113 patent differ at the very feature that primarily distinguishes the ‘113 patent from the prior art, no ordinary consumer familiar with the prior art would believe that the overall visual impression of iPhone 6 and 6 Plus and the ‘113 patent are similar or the same. Additionally, the Court considered many other unique features of iPhone 6 and 6 Plus, including the ring/silent switch, and the H design on the left and right side, etc., to further solidify the conclusion of non-infringement.

‘113 patent prior art prior art iPhone 6

5. Implications

For a long time, the test for design patent infringement in China involves a fair amount of subjectivity and the outcome is especially uncertain in determining whether the accused design is the same as or similar to the patented design. The Apple v. Baili case provides a clear and comprehensive framework for analyzing whether one design infringes another.

Many commentators describe it as a landmark case that brought more certainty to the test of design patent infringement.

The key strategy an accused party could learn from Apple is trying his best to collect prior art references and file an invalidity action against the asserted design patent. The validity challenge can bring possibility of staying the infringement case pending the invalidity decision.

More importantly, strong prior art would significantly limit the expansive scope of the claimed design to increase the likelihood of non-infringement finding. Further, such prior art references can also help narrow the space of design so that dissimilarities in details may be accepted as ground for non-infringement, and support non-functional arguments.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Patent Blog, please subscribe here.