A Markush claim is a type of claim commonly used in chemical and pharmaceutical fields. On December 20, 2017, in Beijing Winsunny Harmony Science & Technology Co., Ltd. v. Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd, (“Daiichi Sankyo Case”), the Supreme People’s Court (“SPC”) resolved a long standing-split among Chinese courts regarding the interpretation and amendment of Markush claims. In combination with examination practice in China, this article will discuss the guidance of the Daiichi Sankyo case and provide strategic suggestions for readers’ reference.

I. The long-standing split on amending Markush claims in China

Under the PRC Patent Law, a Markush claim refers to a single claim defining a plurality of parallel and alternative elements called Markush elements. There is a long-running debate in China over whether a Markush claim should be regarded as an integral technical solution or as a collection of individual technical solutions in parallel.

The Patent Reexamination Board (“PRB”) and several courts followed the “integral technical solution” interpretation, strictly prohibiting the deletion of the alternative option from a Markush claim during the invalidation proceeding, while other courts followed the “collection of parallel individual technical solutions” interpretation, allowing patent owners to amend the Markush claim by deleting alternative option during the invalidation proceeding.

II. Background of Daiichi Sankyo Case

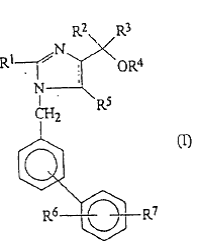

Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd. (“Daiichi Sankyo”) is the patent owner of the Chinese patent No. 97126347.7 (“’477 Patent”). The ’477 Patent includes only one claim, directed towards a method in preparing a pharmaceutical composition for the treatment or for the prevention of hypertension. The method includes that an anti-hypertensive agent is mixed with a pharmaceutically acceptable carrier or diluent, where the anti-hypertensive agent has at least one of a compound with formula (I) or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt or ester thereof in which each of R1 – R7 is independently selected from a list of alternative substituent groups.

In 2010, Beijing Winsunny Harmony Science & Technology Co., Ltd. (“Winsunny”) filed an invalidation petition before the PRB against the ’477 Patent, claiming that the ’477 Patent was not inventive over EP0324377A2, and that Claim 1 lacked sufficient disclosure or clarity. In response, Daiichi Sankyo amended Claim 1 by (1) deleting “or ester” from the phrase “or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt or ester thereof”; and (2) deleting part of alternative substituent groups defined for R4 and R5.

The PRB allowed the deletion of “or ester” and as a result, Winsunny did not assert other invalidation grounds beyond the lack of inventiveness. However, the PRB rejected the deletion of the alternative substituents defined for R4 and R5 on the ground that the deletion generated a new invention beyond the breadth of the original patent document. The PRB further recognized that the prior art, EP0324377A2, disclosed a compound of general formula acting as angiotensin II receptor blocker. Firstly, the comparative compound asserted by Winsunny fell within the general formula but was not concretely disclosed by the prior art, and therefore could not be identified as a qualified primary prior art compound for the inventiveness evaluation. Secondly, the substitute groups defined for the general formula of ’477 Patent were different from those for the general formula in the prior art. Thirdly, Winsunny did not prove that these different substitute groups between ’477 Patent and the prior art can replace each other to achieve the same function. Therefore, the PRB decided that the ’477 Patent was inventive over the prior art EP0324377A2.

Although the Trial Court affirmed the PRB Decision based on the same considerations, the Appellant Court took the opposite position. The Appellant Court regarded the Markush claim as a collection of parallel individual compounds. Therefore, the patent owner was allowed to delete part of the alternative substituent groups. In addition, the Appellant Court also introduced new facts by comparing the technical effects of some examples in the patent with specific examples from the prior art, and found the patent uninventive due to failure to achieve the unexpected technical effects.

The PRB then brought the case to the SPC to petition for a retrial. The SPC, by making clarifications to the following four key questions concerning Markush claims, made a decision to overturn the Appellant Court Decision, and to affirm the decisions of the Trial Court and the PRB.

III. SPC’s Holdings

- A Markush claim is an integral technical solution.

The SPC determined that a Markush claim should be deemed as an integral technical solution, generalizing a class of compounds with the same function rather than a collection of individual technical solutions in parallel according to the requirements of unity for an invention under the PRC Patent Law.

- Amendment of Markush claims should be strictly restricted.

The SPC held that allowing a patentee to arbitrarily delete any Markush element would bring uncertainty to the patent breadth of a Markush claim, which is detrimental to public interests.

Following the SPC reasoning, deleting one or more alternative substitute groups defined for a certain Markush element should be rarely allowed in the invalidation proceeding. However, deleting technical features other than Markush elements is generally allowed subject to the general amendment principle. For example, deleting one form of the compound (“or ester”) is allowed in the Daiichi Sankyo case.

The amendment principle provided in the case is consistent to that of the EPO. In T 948/02, the EPO limited amendments on Markush elements under two conditions: (a) “the deletion must not result in singling out any hither to not specifically mentioned individual compound or group of compounds”; (b) “the deletion does not lead to a particular combination of a specific meaning which was not disclosed originally, i.e. it does not generate another invention”.

- The problem‑and‑solution approach should prevail in the inventiveness evaluation.

The SPC affirmed that the problem‑and‑solution approach should prevail over other tests when evaluating the inventiveness of a Markush claim. The test of “unexpected technical effect” is only applicable when the problem-and-solution approach cannot determine whether the compound of general formula contains an inventive step.

- For a prior art involving a Markush claim, the general formula or a specific compound disclosed can be identified as the primary prior art compound.

The SPC agreed with the Trial Court and the PRB regarding the identification of the primary prior art compound. The SPC ruled that, when the prior art is a patent involving Markush claims, the primary prior art compound can be the general formula or a compound specifically disclosed in the prior art. That is, compounds covered by a general formula but not concretely indicated by claims or description are not considered disclosed, and thus cannot be identified as the primary prior art compound for inventiveness evaluation. Such identification is in line with the “integral technical solution” interpretation of Markush claims.

The SPC ruling is echoed in both the EPO case law and the British judicial practice. According to the established EPO cases law related to the novelty of Markush claims (the eighth edition, Chapter I.C.6.2), “a specific combination of elements requiring the selection of elements from two known groups/lists cannot be regarded as disclosed in the art and so fulfills the novelty requirement”. Likewise, in an England court precedent, Dr Reddy v. Lilly ([2009] EWCA Civ 1362), the High Court held: “it is disclosed to him in a cited reference only when the prior document contains a concrete indication of the claimed compound, such as a description thereof as a preferred embodiment, and if the skilled person is able to produce the compound on the basis of this indication and his general technical knowledge.”

IV. Strategic Suggestions

According to the guidance provided by the SPC in Daiichi Sankyo case, we propose the following suggestions on drafting Markush claim and action strategy in invalidation proceedings.

- Drafting multi-layer claims

The interpretation of Markush claims and the amendment principle require the patent applicant to be more cautious. A blind pursuit for patent breadth might bring huge risks in the invalidation proceedings. Therefore, an effective strategy is to construct multi-layer patent breadth through dependent claims. It’s especially useful to include crucial compounds in independent claims. The dependent claims can be backups for the amendments even if the independent claim is declared invalid. This not only provides more opportunities to withstand invalidation challenges but also helps to occupy a stronger position in potential enforcement actions.

2. Novelty and inventiveness evaluation in invalidation proceedings

- As either the invalidation petitioner or the patent owner, the first focus should be on the non-obviousness of the compound structure, i.e., whether the claimed general formula is obvious or /unobvious compared to the primary prior art compound following the problem-and-solution approach. This is to determine whether the “unexpected technical effect” test shall be applied.

- For the case that the prior art involves a Markush claim, the invalidation petitioner should identify the primary prior art from the general formula or specific compounds concretely disclosed by the patent document.

_____________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Patent Blog, please subscribe here.

Kluwer IP Law

The 2022 Future Ready Lawyer survey showed that 79% of lawyers think that the importance of legal technology will increase for next year. With Kluwer IP Law you can navigate the increasingly global practice of IP law with specialized, local and cross-border information and tools from every preferred location. Are you, as an IP professional, ready for the future?

Learn how Kluwer IP Law can support you.